《1. Introduction》

1. Introduction

The appeal for a water–energy nexus has led to extensive research on environmentally friendly and efficient technologies for clean water production with less energy consumption. Advanced nanofiltration (NF) technology with a precise sieving layer has attracted widespread attention for aqueous treatment systems, as it can operate at lower pressure and achieve molecular separations [1–3]. One of the key challenges for NF is to promote the permeation/separation performance via structural/material design to achieve a promising water–energy nexus. Therefore, it is crucial to adopt new materials and to design particular membrane architectures in order to obtain highly permeable NF membranes with excellent desalination ability and good stability in aqueous solution for practical desalination.

Nature is an endless source of inspiration, as natural materials and technologies have a sophisticated foundation that is worth utilizing in various applications. Natural saccharides and their derivatives have been tentatively employed for constructing NF membranes [4,5]. However, such membranes exhibited unsatisfactory NF performance because of their relatively thick selective layers, which are limited by manufacturing strategies and negativecovalent or non-covalent interactions with the support substrates [6–8]. In contrast, dopamine, as a mussel-inspired catecholamine, can achieve an adhesive material-independent surface coating by self-polymerizing into a polydopamine (pDA) membrane, which has sparked extensive research interest [9–12]. Although pure pDA can modify a porous matrix for NF applications, a single layer of pDA coating is relatively loose, which is not ideal for the rejection of inorganic salts [10], In addition, many nanoparticles accumulate on the surface of the membrane due to non-covalent interactions during the self-polymerization of urinary dopamine [11], which increases the roughness and thickness of the pDA coating membrane and may block membrane pores, causing flux decline. In fact, the amine groups and phenolic hydroxyl groups of pDA can provide practical reactivity with a wide variety of materials [13–15]. To address the issue of the loose and rough layer of NF membranes induced by the conventional coating method, which greatly deteriorates the membrane desalination performance, we conceived of utilizing a new green-resource hydrophilic saccharide-based material to couple with the pDA in order to construct an ultrathin, highly hydrophilic, and precise sieving layer for highly efficient desalination. Such a biopolymer combination provides inspiration for a unique green concept for the fabrication of membranes for molecular-scale separation.

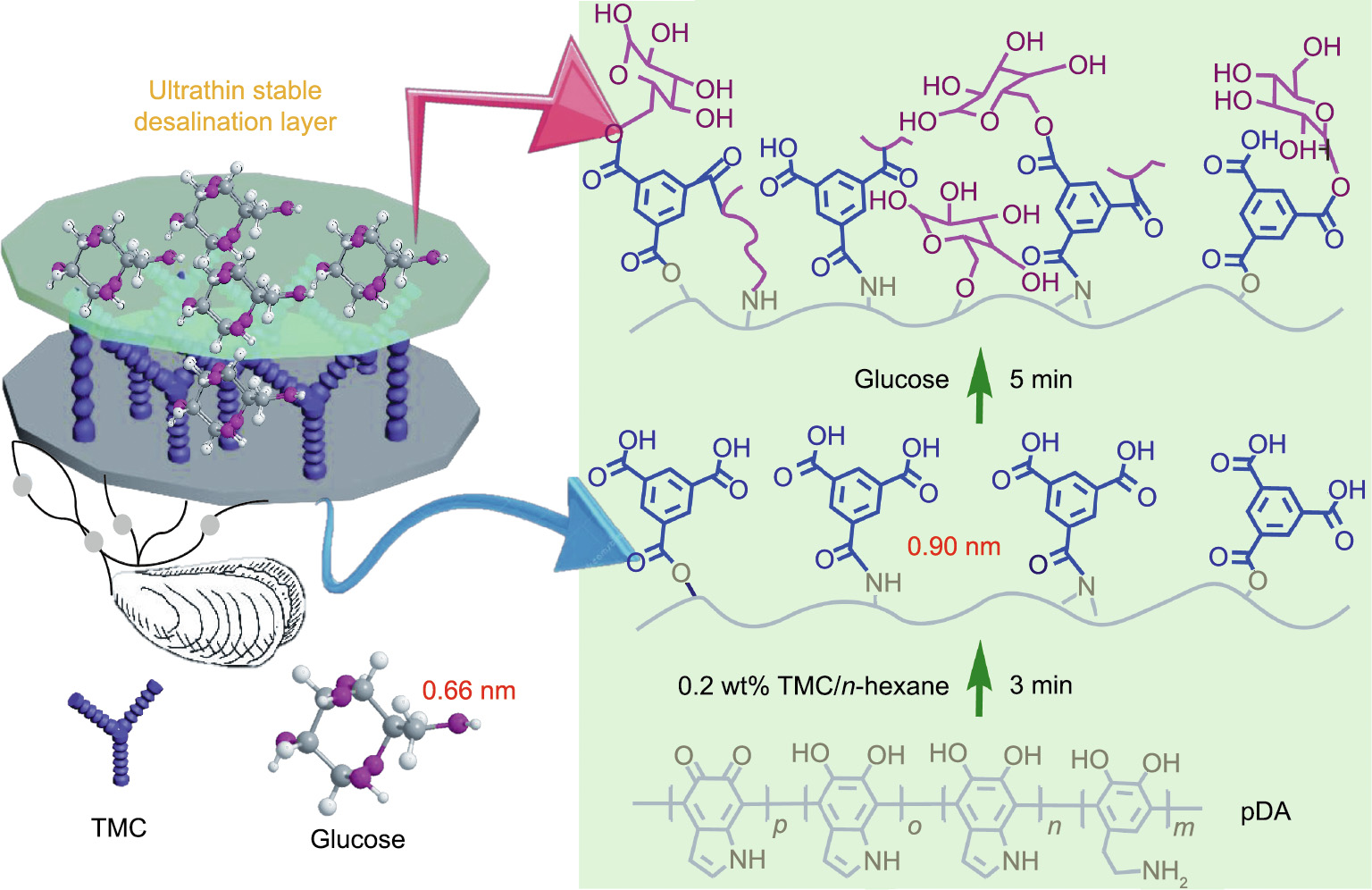

In this research, a novel nanoporous membrane was created using renewable resources, bioinspired by pDA as a key intermediate layer for the interfacial polymerization of 1,3,5- benzenetricarbonyl trichloride (TMC) and glucose to form a hydrophilic, precise, and selective layer for highly efficient desalination. Small glucose molecules (0.66 nm), which possess high hydrophilicity, diffuse into the membrane, and the hydroxyl groups of glucose react with dopamine via an interfacial reaction with TMC; this introduces chemical cross-linking in the interface in order to tune the smaller membrane pores and interrupt dopamine non-covalent interactions, thereby limiting pDA aggregate formation. A defect-free sub-44 nm selective layer can be successfully fabricated. Various characterizations were carried out to analyze the properties of the novel NF membrane. Due to the ultrathin and hydrophilic surface imparted by the renewable materials, the composite NF membrane (named PI-pDA2G) exhibited an ultrahigh Na2SO4 flux and excellent rejections for desalination. Most importantly, the membrane demonstrated excellent long-term stability, as well as tremendous acid-base and alkali-base stability and high anti-pollution capacity.

《2. Materials and methods》

2. Materials and methods

《2.1. Materials》

2.1. Materials

N-Methyl-2-pyrrlione (NMP), MgCl2·6H2O, MgSO4, NaCl, and Na2SO4 were received from Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent, Co. (China). D-(+)-glucose (China), tris(hydroxymethyl)amino methane (Tris), dopamine, isopropanol (IPA), TMC, 1,6-hexanediamine (HDA), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) were provided by Aladdin Industrial Co., Ltd. (USA). The P84 polyimide (PI) raw material was purchased from HP Polymer Gmbh (Austria). All water used was deionized.

《2.2. Forming the highly permeable nanoporous membrane》

2.2. Forming the highly permeable nanoporous membrane

The novel NF membrane was prepared in a clean assembly room (Fig. 1). Porous PI substrates were prepared according to previous reports (Fig. S1 in Appendix A) [16]. The substrate was coated in a Tris–HCl buffer of dopamine hydrochloride (0.2 wt%) for a certain period of time as specified in Section 3.3. The membrane was then washed three times with water. Afterward, the membrane was dried in air and covered with 0.2 wt% TMC hexane solution for 3 min. Then, a glucose solution (1 wt%) containing 0.27% (w/ v) DMAP was added to the membrane surface for 5 min and fixed at 70 °C for 15 min. Thus, a glucose-modified hydrophilic NF membrane (PI-pDA1G) was obtained. NF membranes with different glucose concentrations of 2 wt%, 3 wt%, 4 wt%, and 5 wt% were prepared using the same method and were denoted as PI-pDA2G, PI-pDA3G, PI-pDA4G, and PI-pDA5G, respectively.

《Fig. 1》

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the procedure for constructing the ultrathin and highly hydrophilic nanoporous membrane.

《2.3. Membrane characterizations》

2.3. Membrane characterizations

The surface morphology of the membrane was obtained by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S-4500, Hitachi, Japan) and an atomic force microscope (AFM; Multimode 8, Bruker, USA). The surface chemical composition was characterized by Xray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher, USA) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR; Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher). Wettability in the form of the water contact angle (WCA) was measured by means of a SL 200 KB machine (Kono, USA). The zeta potentials were recorded by adjusting the solution pH from 3 to 10 using 0.1 mol∙L–1 HCl or NaOH.

《2.4. Nanofiltration tests》

2.4. Nanofiltration tests

A home-made filtration system was used to characterize the membrane performance under a pressure of 5 bar (1 bar = 105 Pa) at room temperature, while being continually stirred at 1000 r∙min–1 to reduce the concentration polarization derived from a nitrogen tank. The effective area of the membrane was 21.2 cm2 . The membranes flux was calculated as shown in Eq. (1) [17]:

where F corresponds to the permeation flux (L∙m–2 ∙h–1 ), V is the solvent permeation volume (L), A is the effective membrane area (m2 ), and t is the operation time (h). Solvent rejections were calculated according to Eq. (2) [18]:

where R corresponds to rejection; and Cp and Cf refer to the concentrations of inorganic salts in the permeate and feed solution, respectively, which were determined by means of a conductivity instrument (DOS-307A, Shanghai Leici, China). The calculations of mean pore size and pore-size distribution were based on previously reported methods [19–22]. A long-term stability test was carried out at an operation pressure of 5 bar with Na2SO4 aqueous solution using the PI-pDA2G membrane as the test object. The initial permeances of the membranes were measured after continuous operation for 1 h under a pressure of 5 bar, and the samples were collected for 50 h.

《3. Results and discussion》

3. Results and discussion

《3.1. Exploring the reaction mechanisms for the nanoporous selective layer formation》

3.1. Exploring the reaction mechanisms for the nanoporous selective layer formation

To explore the reaction mechanisms in the formation of the nanoporous selective layer, the presence of glucose and pDA on the PI substrate was validated using FT-IR (Fig. 2(a)). For the pDA coating membrane, a peak at about 3374 cm–1 correlated to the stretching vibrations of the amine and phenolic hydroxyl groups of pDA, while a peak at about 2933 cm–1 corresponded to the –CH2– stretch in pDA. The aromatic rings of pDA contributed to peaks at about 1640 and 1530 cm–1 [23,24]. To facilitate the subsequent coupling of glucose and pDA, we introduced trimesoyl chloride onto the pDA layer. This resulted in a redshift of the peak at about 3374 cm–1 to about 3283 cm–1 , while drastically reducing the intensity of this peak. This peak was broadened further when glucose was coupled onto the membrane surface, due to the introduction of more –OH groups by the formation of new amide bonds via nucleophilic reactions between glucose hydroxyl groups and pDA, and to the formation of ester bonds between glucose hydroxyl groups and TMC acyl chlorides [25].

《Fig. 2》

Fig. 2. (a) FT-IR spectra and (b) XPS characterization of the fabricated membranes, including cross-lined PI, PI-pDA, PI-pDA-TMC, PI-pDA2G, and PI-pDA5G.

XPS was also deployed to verify the presence of glucose and pDA (Fig. 2(b), Fig. 3, and Table S1 in Appendix A) in the membrane regulated by natural materials. After being coated with pDA, the membrane demonstrated higher oxygen content (from 16.94% (PI) to 22.62%), due to the high percentage of oxygen in pure pDA [26]. Furthermore, the peak at 531.1 eV (C=O*) (1 eV = 1.602 ×10–19 J) of PI was significantly weakened, while a new peak at 532.9 eV (=C–O*H) formed, whose appearance was attributed to the phenolic hydroxyl groups of pDA (Figs. 3(a) and (b)) [27]. In addition, after TMC grafting, the carbon content increased from 70.33% (PI-pDA) to 81.24%, with a new peak at 533.3 eV (the –O*–C=O and H*O–C=O moieties in TMC) (Fig. 3(c)) [24]. Compared with the PI-pDA-TMC membrane, the PI-pDA2G membrane exhibited a wider, enhanced peak at 533.1 eV (O*–C=O) (Fig. 3(d)). Moreover, the oxygen content obviously increased from 14.39% to 16.01% when glucose was coupled onto the PI-pDA-TMC layer, due to the introduction of more –OH groups from glucose, with the formation of covalent bonds through the reaction of acyl chlorides with pDA [28]. Therefore, the XPS results were consistent with the FT-IR results, confirming the occurrence of the designed glucose/pDA interfacial reaction and the formation of the novel membrane.

《Fig. 3》

Fig. 3. High-resolution and deconvolution of O 1s spectra of the membranes: (a) cross-lined PI, (b) PI-pDA, (c) PI-pDA-TMC, and (d) PI-pDA2G.

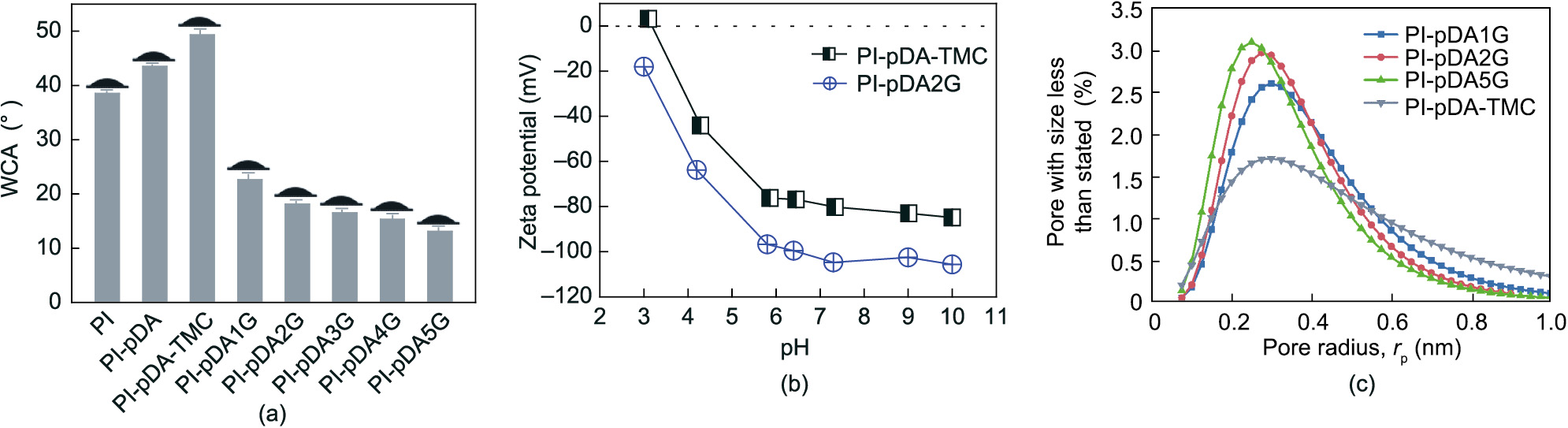

While the pre-treated membrane was immersed in the glucose solution, some of the glucose formed covalent bonds on the surface, which improved the hydrophilicity and tunable surface charges of the separation layer. The –OH groups of the nanoporous membrane loaded with glucose remained highly hydrophilic—a key requisite for a high-performance and antifouling nanoporous membrane [29]. The PI-pDA membrane had a visibly higher WCA (43.5° ± 0.2°) compared with the pristine cross-lined PI substrate (38.5° ± 0.2°), which can be explained by the introduction of the hydrophobic benzene ring structure at the pDA layer. After the grafting of TMC, the WCA of the PI-pDA-TMC selective layers was 49.3° ± 0.5°; in the presence of glucose, it sharply decreased to 22.6° ± 0.8° for PIpDA1G, 18.1° ± 0.6° for PI-pDA2G, 16.5° ± 0.2° for PI-pDA3G, 15.3° ± 0.5° for PI-pDA4G, and 13.1° ± 0.3° for PI-pDA5G (Fig. 4(a)). The hydrophilic –OH groups also reduced the zeta potential of the PI-pDA-TMC selective layers. The PI-pDA2G membrane presented a negative charge at pH values ranging from 3 to 10. When the pH value was 7, the zeta potential of PI-pDA2G was –104.8 mV (Fig. 4(b)), resulting in a remarkable NF performance for ions with the same charge.

《Fig. 4》

Fig. 4. (a) WCAs of the fabricated membranes, including cross-lined PI, PI-pDA, PI-pDA-TMC, PI-pDA1G, PI-pDA2G, PI-pDA3G, PI-pDA4G, and PI-pDA5G; (b) zeta potential of the fabricated membranes PI-pDA-TMC and PI-pDA2G; (c) pore-size distribution of the fabricated membranes PI-pDA1G, PI-pDA2G, PI-pDA5G, and PI-pDA-TMC.

The effective pore sizes of PI-pDA-TMC, PI-pDA1G, PI-pDA2G, and PI-pDA5G were also tested to confirm the occurrence of the reactions of glucose with dopamine and TMC via interface reactions. The PI-pDA-TMC membrane had a wide pore-size distribution, with many of the pores being larger in size than glucose (0.66 nm) (Figs. 1 and 4(c)); this finding demonstrated that glucose can diffuse into the pores to eliminate the defects of the PI-pDA-TMC pre-treated membrane. As the glucose concentration increased, the pore-size distribution of the membranes narrowed, and the pore sizes also gradually decreased (Fig. 4(c)). Thus, small glucose molecules can covalently react with TMC, reducing the pore size of the membrane and tuning the pore diameter, which is conducive to improving the desalination performance.

Herein, based on the above chemical characterization results, the reaction mechanisms for the interfacial-reaction-based composite membrane between glucose and dopamine can be summarized as follows: As a small molecule (0.66 nm), glucose can diffuse into the membrane and form covalent bonds with TMC and pDA; these bonds endow the membrane with a smaller pore size and significant stability for efficient desalination. In addition, the glucose molecules can greatly improve the hydrophilicity and tune the surface charges of the separation layer to improve permeability. The synergetic effect of green-resource-derived pDA and glucose can lead to membranes with excellent NF performance for desalination.

《3.2. Observation of various membrane morphologies》

3.2. Observation of various membrane morphologies

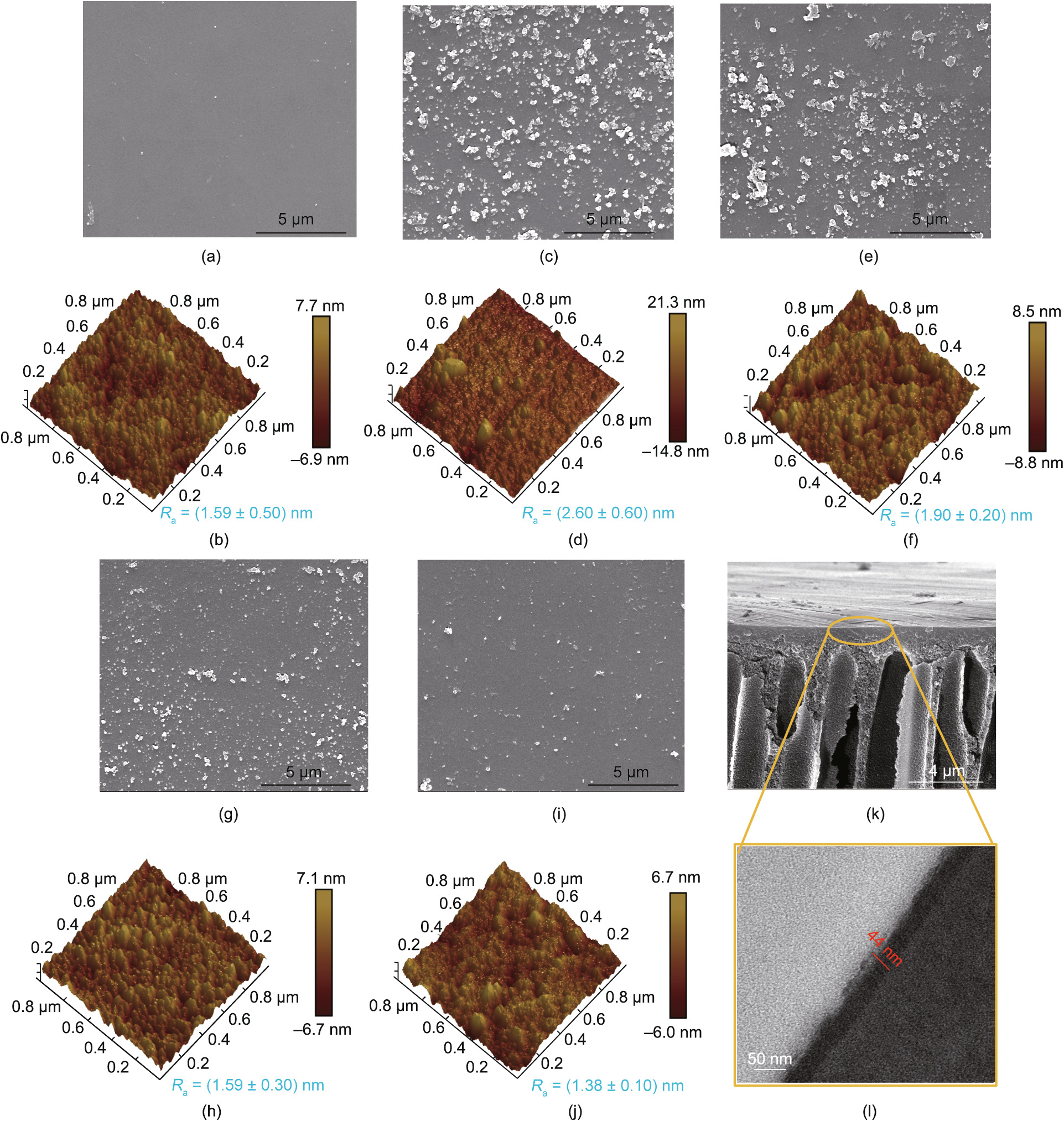

Membrane morphologies—especially selective layer morphologies—are crucial in determining membrane performance. The surface morphologies of various membranes during the selective layer building process were characterized by SEM and AFM (Figs. 5(a)–(j)). The neat cross-linked PI membrane exhibited a smooth surface (roughness Ra = (1.59 ± 0.50) nm) (Figs. 5(a) and (b)). A large number of particles appeared on the surface of the dopamine-modified membrane, resulting in an increase of Ra from (1.59 ± 0.50) to (2.60 ± 0.20) nm (Figs. 5(c) and (d)), which indicated the formation of a pDA coating on the substrate during the dopamine self-polymerization process. When the pDA-modified membrane was grafted with TMC (PI-pDA-TMC), the reduction in the size and number of particles led to a decrease of Ra ((1.90 ± 0.20) nm) (Figs. 5(e) and (f)). The further introduction of glucose caused the resultant membrane to possess only a relatively small number of particles on the surface (Figs. 5(g) and (i)). Most importantly, the decrease in the Ra value (Figs. 5(h) and (j)) after the introduction of glucose indicated that the resultant membrane had smoother surfaces, which was consistent with the trend of the SEM results. To examine the exact thickness of the constructed selective layer, cross-sectional SEM and transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of PI-pDA2G were obtained, as shown in Figs. 5(k) and (l). The thickness of the layer was found to be about (44 ± 5) nm. An ultrathin and smooth selection layer are crucial in achieving high-performance membranes for desalination.

《Fig. 5》

Fig. 5. (a–j) SEM and AFM images of the NF membranes, including (a, b) cross-lined PI, (c, d) PI-pDA, (e, f) PI-pDA-TMC, (g, h) PI-pDA2G, and (i, j) PI-pDA5G; (k, l) crosssectional SEM and TEM images of PI-pDA2G.

《3.3. Desalination performance of the nanoporous membranes》

3.3. Desalination performance of the nanoporous membranes

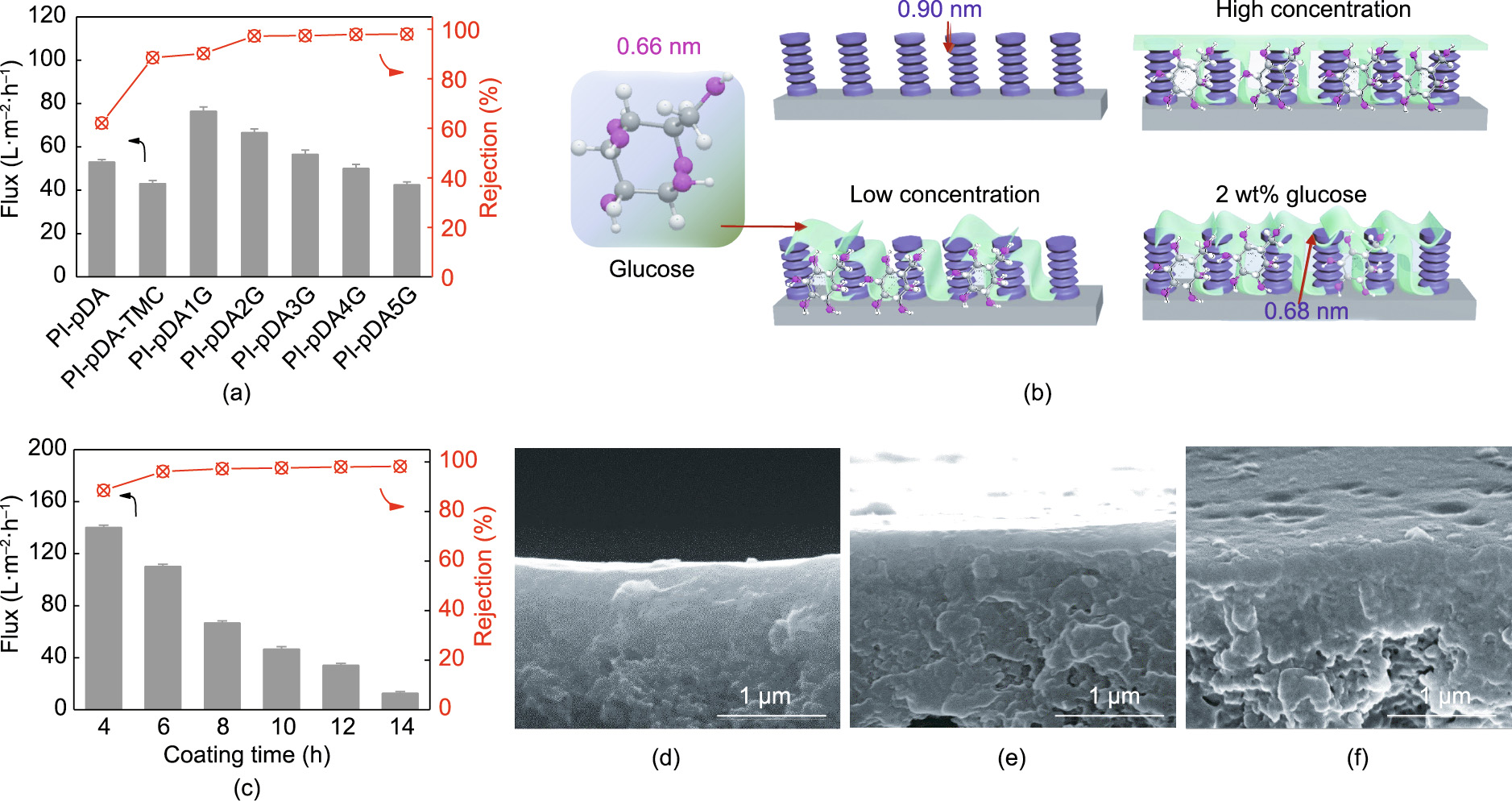

Fig. 6(a) demonstrates the excellent separation capabilities of our synthesized glucose-assisted membranes for desalination. The concentration of glucose molecules affected the performance of the NF membranes, because glucose forms covalent bonds with TMC on the surface and penetrates into the PIpDA-TMC layer to tune the membrane structure. Therefore, the presence of glucose drastically improved both the Na2SO4 flux and the rejection compared with those of the pDA-coated membrane, which had a low-level Na2SO4 flux and poor rejection (62.1%). In fact, glucose with its abundant –OH groups significantly enhanced the hydrophilicity and increased the negative charge of the membrane surface, while simultaneously reducing the pore size of the membranes and tightening the membrane structure. The PI-pDA1G membrane with a low level of glucose introduction showed a generally improved Na2SO4 flux from 43.0 to 76.5 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 and an increased rejection from 78.5% to 90.2% compared with those of the PI-pDA-TMC. After increasing the glucose concentration to 2 wt%, the Na2SO4 flux gradually decreased from 76.5 to 66.5 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 ; however, the Na2SO4 rejection was enhanced to 97.3% due to the denser and more uniform separation layer on the membrane surface and the relatively small pore radius (0.34 nm) in the NF pore-size range (Figs. 4(c) and 6(b)). As the concentration of glucose was increased up to 5 wt%, the Na2SO4 flux decreased, while the Na2SO4 rejection was maintained at about 97.5% due to the increased mass transfer resistance.

The pDA coating time greatly influenced the nanoporous membrane performance, so it required optimization. By varying the pDA coating time, the separation performance of the as-prepared nanoporous membranes (2 wt% glucose) was examined with the Na2SO4 aqueous solution; the results are demonstrated in Fig. 6(c). As the pDA coating time increased from 4 to 14 h, the Na2SO4 flux decreased significantly. This result should be due to the size sieving effect, as there was a decrease in membrane pore size and enhanced mass transfer resistance due to the anchoring of pDA onto the internal walls of the pores [30,31]. Furthermore, due to the increased layer thickness (Figs. 6(d)–(f)), the Na2SO4 rejection increased from 88.5% (4 h) to 97.3% (8 h). However, after the coating time was extended to 14 h, the rejection remained almost constant. Therefore, 8 h was determined to be the optimum pDA coating time for building our nanoporous membrane.

《Fig. 6》

Fig. 6. (a) Effects of glucose concentration on the Na2SO4 rejections and Na2SO4 flux with a pDA coating over 8 h; (b) illustrations of the membrane formed by a low glucose concentration, 2 wt% glucose concentration, and high glucose concentration (glucose is shown in green); (c) effect of pDA coating time on the Na2SO4 rejections and Na2SO4 flux of PI-pDA2G; (d–f) cross-sectional SEM images of PI-pDA2G membranes with different pDA coating times of (d) 4 h, (e) 10 h, and (f) 14 h.

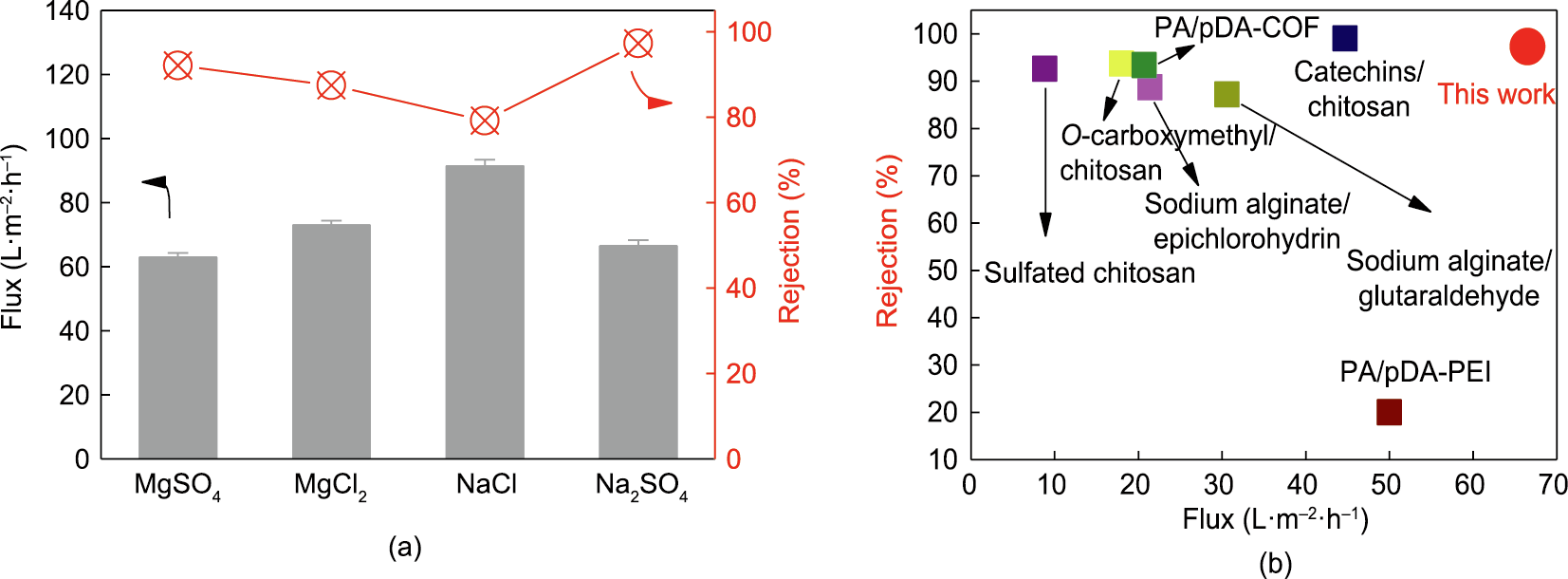

To further examine the membrane desalination performance, the PI-pDA2G membrane was evaluated at a pressure of 5 bar with various inorganic salts (MgSO4, MgCl2, NaCl, and Na2SO4) (Fig. 7(a)). The PI-pDA2G membrane showed high fluxes of 66.5 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 for the Na2SO4 solution and 63.0 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 for the MgSO4 solution, which were higher than those reported in the literature [32–34]. The rejection decreased in the following order: Na2SO4 (97.3%) > MgSO4 (92.1%) > MgCl2 (89.5%) > NaCl (80.2%). This finding suggests that the membrane can well reject the divalent anion SO42–; it aligns with the Donnan exclusion effect [24,35], because the PI-pDA2G membrane was negatively charged under the testing conditions [24]. The rejection of MgCl2 and NaCl was slightly lower than that of Na2SO4 and MgSO4; however, the rejection for MgCl2 and NaCl was still higher than 80%. These results indicate that the interfacial reaction (i.e., coating) can not only adjust the structure of the top ‘‘skin” layers of the membranes and ‘‘block” the big pores but also simultaneously improve the surface hydrophilicity and tune the surface charge of the membrane. Compared with the reported data [7,36–41], the green-resource-based nanoporous membrane in our study exhibits the best Na2SO4 rejection and Na2SO4 flux performance among the membranes composed of natural products (Fig. 7(b)).

《Fig. 7》

Fig. 7. (a) Fluxes and rejections of the PI-pDA2G membrane for different inorganic salt aqueous solutions at a pressure of 5 bar and pH = 7; (b) comparison of Na2SO4 rejection and Na2SO4 flux with selective layers composed of natural products (round symbols represents PI-pDA2G in this work, while squares represent membranes with selective layers composed of other natural products). COF: covalent organic framework; PEI: poly(ethylene imine).

《3.4. Stability of the nanoporous membrane》

3.4. Stability of the nanoporous membrane

Membrane stability plays an important role in long-term practical operation. As shown in Fig. 8(a), our PI-pDA2G membrane exhibited an extremely stable filtration performance. No discernible degradation of the PI-pDA2G membrane performance was observed during tests over 50 h with Na2SO4 solution at the transmembrane pressure of 5 bar. In addition, the Na2SO4 flux of the membrane exhibited a linear increase, and the rejection displayed a stable high value as the pressure was increased to 10 bar (Fig. 8(b)). Even in a high-concentration of Na2SO4, the PIpDA2G membrane maintained a relatively high rejection (Fig. 8(c)).

《Fig. 8》

Fig. 8. (a) Time-dependent Na2SO4 flux and rejection of PI-pDA2G membranes for Na2SO4 aqueous solution; (b, c) NF performance of the PI-pDA2G membrane with (b) different pressure changes and (c) different concentrations of Na2SO4.

In practical separation applications, the cleaning process of a membrane often involves acid or alkali treatment and vibration ultrasound. As shown in Figs. 9(a)–(e), the prepared PI-pDA2G membrane was immersed in 0.1 mol∙L–1 HCl (0.1 mol∙L–1 NaOH) for 24 h or exposed to ultrasound for 8 h at 40 kHz, following which the separation performance was tested. The membrane still maintained a relatively high flux and rejection, with a slight change in Ra due to the falling off of dopamine self-polymerization nanoparticles, which did not affect the stability of the membrane. Both the strong adhesion of pDA to the cross-linked PI and the chemical bond linkages between glucose and pDA and TMC granted excellent stability to our green-resource-based nanoporous membrane.

《Fig. 9》

Fig. 9. (a–d) AFM and SEM images of the PI-pDA2G membrane after (a, c) acid or (b, d) alkali treatment; (e) NF performance of the PI-pDA2G membrane after ultrasonic, acid, or alkali treatment; (f) normalized flux of the PI-pDA2G membrane in the antifouling test (1 g∙L–1 BSA or HA); (g, h) FRR, DRt, irreversible fouling ratio (DRir), and reversible fouling ratio (DRr) values of the membrane during the ternary-cycle filtration test using BSA/HA as the model foulant.

Fouling affects membrane performance and shortens the life of the membrane, so it is a common major problem in membrane separation processes [42,43]. The antifouling performance of the PI-pDA2G membrane was estimated by 1 g∙L–1 bovine serum albumin (BSA) or humic acid (HA) solutions for 30 h (Fig. 9(f)). The flux recovery (FRR) of the PI-pDA2G membrane was 92.8% for BSA and 96.3% for HA, with a low total fouling ratio (DRt) (HA 4.9%, BSA 13.0%) (Figs. 9(g) and (h)).

The PI-pDA2G membrane exhibited better antifouling property with HA than with BSA because the molecular size of BSA (7.5 nm) is much smaller than that of HA (92 nm) and tends to form a denser contamination layer on the membrane surface [44,45]. The membrane’s excellent resistance to these hydrophobic contaminants was also due to the hydrophilicity and negative charge of the membrane. Since both BSA and HA molecules are negatively charged, the Donnan exclusion mechanism contributed to the membrane’s resistance to biofouling.

A membrane’s mechanical properties also have an important impact on its practical application. We determined the mechanical properties of the PI-pDA2G membrane (Fig. S2 in Appendix A). The tensile strength of the PI-pDA2G membrane was (2.69 ± 0.10) MPa and the Young’s modulus (calculated by the stress–strain curve) was (38.0 ± 0.5) MPa. These test results show that the prepared PIpDA2G membrane has a relatively good mechanical stability, which is conducive to increasing the practical value of the membrane.

《4. Conclusions》

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have presented a facile technique to produce highly permeable nanopore-based NF membranes by employing glucose and pDA via interfacial reactions. Control of the preparation parameters allowed for the fabrication of a novel NF membrane. The addition of glucose endowed the PI-pDA2G membrane with a highly hydrophilic, ultrathin surface and a negative charge. In addition, it exhibited a high Na2SO4 flux and excellent rejections of Na2SO4 (66.5 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 , 97.3%) and MgSO4 (53.0 L∙m–2 ∙h–1 , 92.1%) aqueous solutions, which were higher than those of previously reported NF membranes made of natural products. Furthermore, a long-term separation test of the Na2SO4 aqueous solution, acid-base and alkali-base, ultrasonic treatment, and anti-pollution testing were carried out and revealed that our membrane exhibits a stable separation performance in industrial environments and can be used to construct NF membrane selective layers with other natural materials.

《Acknowledgments 》

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21878062) and the Open Project of the State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment (Harbin Institute Technology) (QA201922).

《Compliance with ethics guidelines 》

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Yanqiu Zhang, Fan Yang, Hongguang Sun, Yongping Bai, Songwei Li, and Lu Shao declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

《Appendix A. Supplementary data 》

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.06.033.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号