1. Introduction

Research on social media has become a very successful topic in recent years. One of the research streams regarding social media focuses on technology. Most researchers in computer science use this type of research methodology to analyze users’ behavior on social media and develop automatic intelligent services for users. The other research stream on social media focuses on the aspects of management and other social sciences. Among these kinds of research, information systems (IS) is one of the main areas producing research on social media. Unlike the technical research stream, in the second research stream, multiple disciplines are used to understand the usage of social media, such as data science, social science, behavioral science, or design science. Among these many disciplines, some are more popular than others. For example, the topic of this research paper is the application of philosophy to social media, in part because such a topic is usually overlooked in favor of sociology-related studies in social media. However, for the purpose of suggesting a theoretical framework to understand human’s social media usage behavior, philosophy provides a more basic foundation than sociology. Combining sociology and philosophy will allow us to obtain more powerful theoretical tools to explore people's deep requirement for social media usage; such work will also lend strong support to the technology research stream on social media.

Current IS research on social media use may be characterized by reductionism and universalism. Whereas reductionism appears through a lack of alternative theories, universalism is to be found in a lack of contextualization of the findings. In contrast to reductionism and universalism, this study suggests a journey toward pluralism and contextualization: Pluralism requires a manifold of theoretical perspectives, and contextualization demands an outline of a contingency model.

The research questions that have been raised so far may be reworded in the form of the following axiomatic:

(1) Which philosophical foundations may be relevant to compare different theories regarding social media?

(2) What is the respective contribution of the different theories that are applied to the use of social media?

(3) Which of these theories match with findings in the IS literature regarding social media?

Although many theoretical perspectives may qualify, only four theoretical perspectives are considered here: Goffman’s presentation of self, Bourdieu’s social capital, Sartre’s existential project, and Heidegger’s ‘‘shared-world.” The first two perspectives have been extensively used in IS research to analyze the use of social media; however, fewer publications focus on the second two perspectives.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the framework, and Section 3 discusses the application of these four theories to social media and compares them with empirical findings in the IS literature. Section 4 outlines a contingency model for these theories. In Section 5, we give the conclusions and point out the contribution of this paper.

《2. Framework》2. Framework

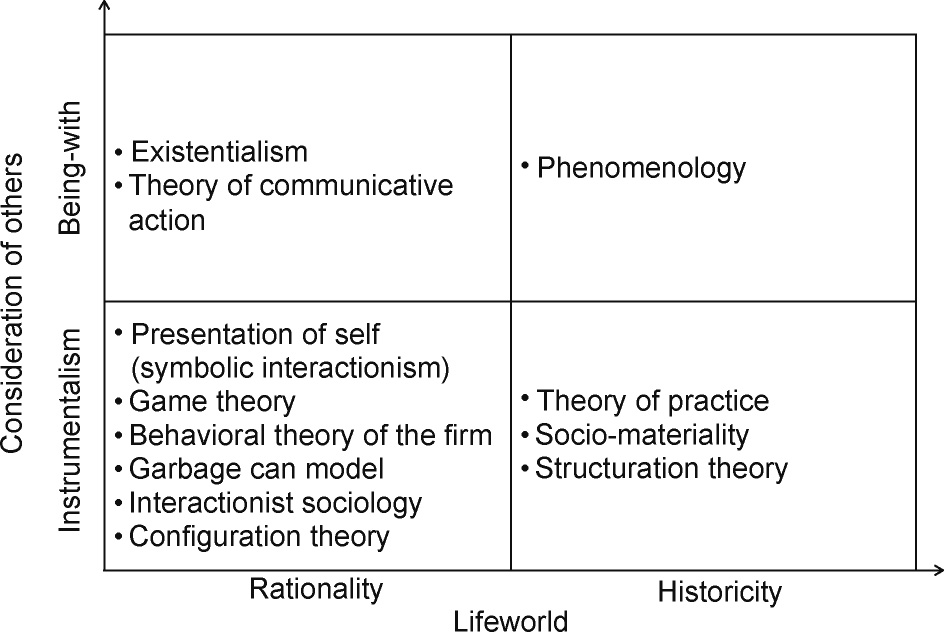

How can the use of social media be described? Here, we suggest a framework elaborated from philosophy. The horizontal axis describes the lifeworld, which may be dominated by either rationality or historicity. The vertical axis relates to consideration of others, in that others may be considered either as means or as ends. Considering others as means is the characteristic of instrumentalism, whereas considering others as ends is consistent with "being-with” (Fig. 1).

《Fig.1》

Fig. 1. A framework describing the use of social media.

A lifeworld is not made of objects, but of history. Heidegger [1] elaborated on the idea of a lifeworld based on history, and introduced the opposition between rationality and historicity. Descartes elaborated on a rational philosophy called "Cartesianism,” which is based on the separation between the mind and any other object in the world. As introduced by Husserl, history creates meaning in a person’s lifeworld. Heidegger defined the way in which ancient worlds are still present in our being and an authentic mode of being by the word historicity.

The way we consider others was introduced into IS through Habermas’ theory of communicative action [2,3]. Habermas asked a question about the way we consider others: Do we use others as instruments to achieve our objectives or do we consider them as an end in themselves? If we consider others as means, we are acting in an instrumental manner. If we consider others as ends, we are in a position that Heidegger called ‘‘being-with-others.”

《3. Archetypical theories》3. Archetypical theories

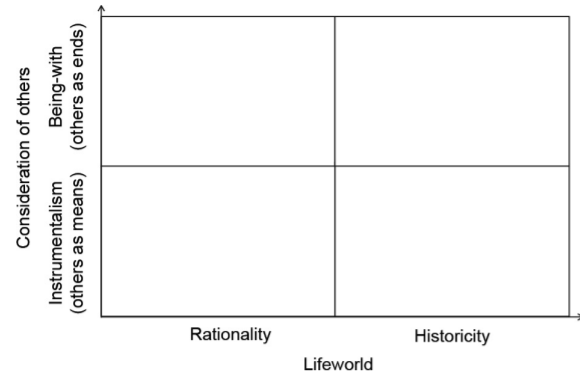

Many theories have been suggested regarding the use of IS in an organizational context. Although the mainstream assumes that IS leads to performance, especially in regard to enterprise social media [4], a wide range of references coming from organization science are less optimistic. Instead of information sharing, an important trend in organization studies assumes that information itself is power, and that power stems from information retention. For example, this trend is represented by theories such as the behavioral theory of the firm [5], agency theory [6], the theory of organizational choice known as the "garbage can model” [7], inter-actionist sociology [8], and the configuration theory [9]. The presentation of the self, also known as symbolic interactionism [10], and game theory [11] are part of this trend as well. Because of the distantiation of others that is part of this trend, this kind of rationality can be described as conflictual; it is also called instrumental action by Habermas [2]. However, of all these theories, Goffman's presentation of self [10] is the only one that has been widely used to examine IS within social media. Because these theories rely on an image of humans acting through rationality, these theories correspond to Descartes’ rational view where a rational observer is detached from the world. However, many theories have criticized the assumption of rational choice theory. One of these theories in IS is actor-network theory, considered as a socio-material theory. This theory suggests a focus not only on human agency, but on material agency as well. Thus, certain objects such as a meeting room, a building, a spreadsheet, or a software, which are referred to as ‘‘actants,” may have an equal influence as human agency [12]. Another alternative theory used in IS is structuration theory, which stresses the influence of the structure on individual action [13]. So far, however, Bourdieu’s theory of practice [14] is the only theory that is able to analyze not only power at both the organizational and individual levels, but also the way individual behavior reproduces structure through the concept of habitus. Due to the influence of the outside world on our actions, the concept of habitus may be considered as an approximation of "inner worldliness.” Others are present in each aspect of our behavior, including our judgment of taste. Although the view of the world provided by the theory of practice includes an approximation of innerworldliness through habitus, it retains an instrumental stand-point toward others because of the concept of a "strategic move,” as described hereafter.

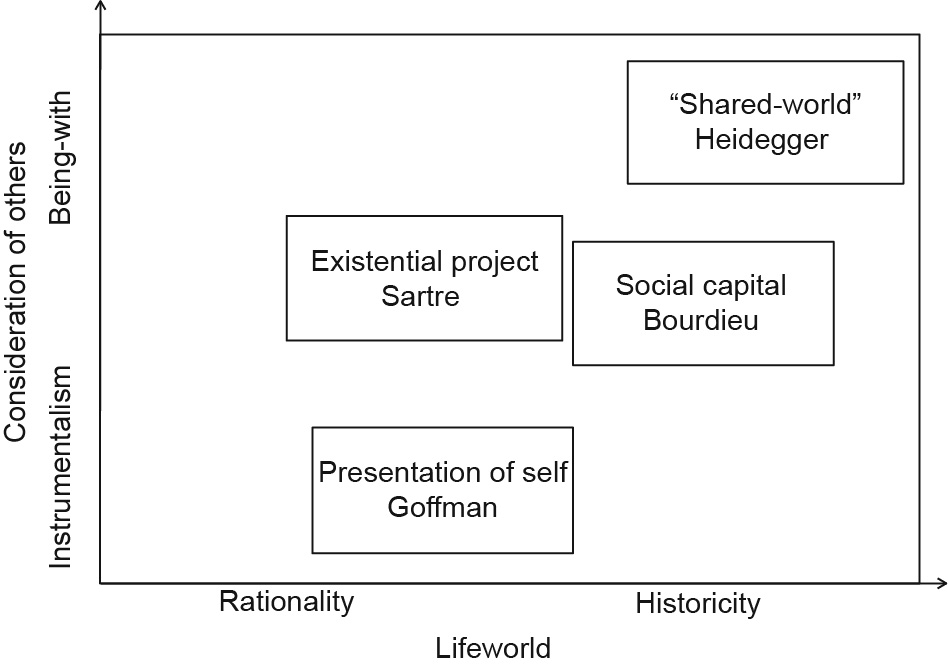

In contrast, an approximation of "being-with” can be found in Habermas [2] through the concept of communicative action. Instrumental action is oriented toward success and occurs in a non-social world where we use others; it refers to distantiation. Communicative action is oriented not toward success, but toward understanding; the world is considered as social. Therefore, the status of others moves from means to ends, which is consistent with Heidegger's "being-with.” However, because of its linguistic assumptions, Habermas’ work [2] remains within the rationality perspective, especially in terms of the idea of argumentative rationality. Also, while the theory of communicative action has been extensively applied at the level of an organization or at the level of society, its relevance at the level of an individual is questionable. On the other hand, a theory of "being-with” at all levels, including the individual level, can be found in Sartre’s concept of the "existential project,” which is the meaning we give to our life. Indeed, through his description of concrete relations with others, Sartre claims that others are included in our existential project, and his theory is therefore consistent with Heidegger's "being-with.” What is an existential project? Sartre claims that this is a decision that each of us makes sooner or later. This decision relies on a concept of freedom that is therefore related to Descartes’ rationalism. The only theory that combines both innerworldliness and "being-with” is Heidegger's theory of the "shared-world” (Fig. 2).

《Fig.2》

Fig. 2. Theories related to each configuration of the framework.

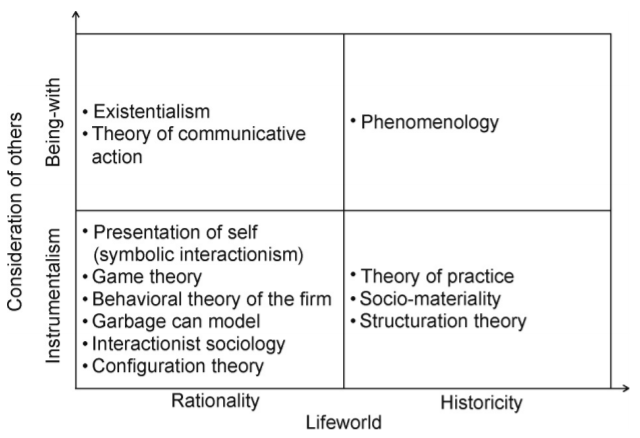

Therefore, despite the manifold of possible theories for under-standing social media use in everyday life, this paper utilizes only four archetypal theories: Goffman's symbolic interactionism, Bourdieu’s theory of practice, Sartre's existentialism, and Heidegger's phenomenology. Within each of these four archetypal theories, only one concept will be selected for of its potential relevance to social media: Goffman’s presentation of self, Bourdieu's social capital, Sartre's existential project, and Heidegger's "shared-world” (Fig. 3).

《Fig.3》

Fig. 3. Four archetypical theories for each configuration of the framework.

《4. Using archetypical theories to understand social media》4. Using archetypical theories to understand social media

While the category of lifeworld includes the modalities of Descartes’ rationality and Heidegger's historicity, the category of consideration of others includes the modalities of instrumentalism as opposed to Heidegger's "being-with.” This section outlines the framework where different archetypal theories applied to social media may be compared: Goffman's presentation of self, Bourdieu's social capital, Sartre's existential project, and Heidegger's "shared-world.”

《4.1. Social media and Goffman's presentation of self》4.1. Social media and Goffman's presentation of self

4.1.1. Goffman's presentation of self

Goffman’s book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life [10] introduces the "way to present”: "Regardless of the particular objective which the individual has in mind” (p. 3), and "Thus, when an individual appears in the presence of others, there will usually be some reason for him to mobilize his activity so that it will convey an impression to others which it is in his interests to convey” (p. 4).

(1) Lifeworld. The presentation of self serves an objective. It conveys an impression to others that lies in accordance with one's own interest. Goffman’s book is therefore all about the outward appearance of action [1]. This outward appearance is first applied to the agent. The presentation of self is the way we appear objectively before others. Others will form an opinion about us through perceptual rationality. Others are perceived in turn through their external objective qualities and appearance. "Others” are not the same as "us.”

Moreover, Goffman’s book introduces ‘‘the way in which the individual in ordinary work situations presents himself and his activity to others, the way in which he guides and controls the impression they form of him, and the kinds of things he may or may not do while sustaining his performance before them” (preface). Here, the analogy of Cartesian dualism—between the thinking subject and the world as a space or territory that the subject will influence—is fully relevant.

This relevance is confirmed by the fact that "This control is achieved largely by influencing the definition of the situation which the others come to formulate” (p. 4). In this perspective, the world is not somewhere we live or dwell, somewhere familiar, or somewhere we remain; rather, the world is a stage. Further-more, that stage is temporary and a-temporal. There is no past, and the only objective is to achieve an objective. The description of the world of others is reduced to the strict minimum that is necessary for performing the action. Indeed, the whole book is intended to "serve as a sort of handbook” (preface). Therefore, the lifeworld assumed by Goffman's presentation of self is closer to rationality than to "being-in-the-world.”

(2) Others. The status of "others” is introduced by Goffman through the principle that the agent should express "himself in such a way as to give them the kind of impression that will lead them to act voluntarily in accordance with his own plan.” (p. 4). Others are supposed to be led to "act in accordance with his plan.” Such a status of the other has clear aspects of instrumentalism [1], not to say instrumentalization. Such an instrumental status of others is confirmed by the notion of control: "it will be in his interests to control the conduct of the others” (p. 3).

Goffman's theory leans toward instrumentalism through the concept of "move,” which is described in his book Strategic Interaction [11]. A strategic interaction is based on game theory. There are "game-like situations” when a person can "influence his own decision by his knowing that the other players are likely to try to dope out his decision in advance. . . An exchange of moves made on the basis of this kind of orientation to self and others can be called strategic interaction” [11]. After being described as a stage, the world becomes a chess board and a territory for conquest. All the dimensions of instrumentalism are present in this situation: Agents totally unrelated to others, alien relationships, not mattering to one another, and passing one another are the least that can be said of such relationships dominated by mistrust. As noted by Apel in his book Towards a Transformation of Philosophy [15], the ultimate stage of conflict recreates objective-like situations. Indeed, the being of others causes the pure objective presence of several subjects—which would rather be called agents here—to disappear. Therefore, the status of others, in Goffman’s presentation of self, incorporates a position of instrumentalism.

4.1.2. Social media and Goffman’s presentation of self

Empirical research regarding social media found that people use social networking services (SNS) in order to present themselves as better than they actually are [16]. Peoples’ online identity is more imaginative than their true self [17]. Young people tend to facilitate their life, which they perceive as complicated [18–21]. This improvement of the virtual self on SNS is related to the work of Goffman [11]. Our presence on social media seems to be customized for an audience [22].

In the context of a public and accessible narrative of a "brand,” micro-blogging sites that allow messages to be viewed publically across a platform and to spread through likes and re-shares (such as the Twitter's re-tweet) are ideal for personal brand construction. The relatively limited and short messaging style, coupled with easy categorization of a theme through a hashtag (#), allows a presentation of cultural, social, and political interests in a consistent and visible manner. While other SNS are characterized by limited connections with others based on shared geographies, circum-stances, or personal histories, micro-blogging sites allow people to make connections with any other person on the network, regardless of whether the persons involved know one another or are connected in any other way, and to present the self in a representational manner. A comparison of the characteristics of social media use extrapolated from Goffman’s presentation of self and empirical findings is suggested in Table 1.

《Table 1》Table 1 Goffman’s presentation of self theory compared with findings in IS literature.

4.2. Social media and Bourdieu's social capital

4.2.1. Bourdieu's social capital

Social capital is defined as an aggregation of resources that is linked to the possession of a durable network of relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition—or, in other words, to membership in a group. This capital provides each of its members with the backing of the collectively-owned capital, a ‘‘credential” that entitles them to credit [14]. The profits that accrue from member-ship in a group are the basis of the solidarity. This does not mean that these profits are consciously pursued as such. First, Bourdieu’s lifeworld is clearly positioned in opposition to rationality. The concept of habitus (inherited dispositions) ‘‘has the virtue of pushing aside interpretations in terms of ‘rational choice’” [23]. However, the status of others remains in instrumentalism.

(1) Lifeworld. Through the concept of habitus, Bourdieu’s life-world in social capital is consistent with innerworldliness. Indeed, Bourdieu [14] claims that all our actions are influenced by contextual factors such as our education level or our social origins, even the judgment of taste. ‘‘The human mind is social, bounded, socially structured” [23]. The influence of social structure is radically opposed to a rationality that is separated from the world. The mind, which is the prerogative of the subject, becomes an object of the world. The subjectivity of the subject itself disappears: ‘‘The individual, and even the personal, the subjective, is social, collective” [23]. The agent is dissolved into the group, and the group into external factors such as structures. Even the judgment of taste, which we assume to be one of the most personal and subjective judgments, becomes collective and social. In his book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste [24], Bourdieu claims that we find pieces of art beautiful not because they are intrinsically beautiful, but because of our social origins. This explanation of such differences of taste is bound up with the ‘‘system of dispositions (habitus) characteristics of the different classes. . . Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier” [24]. The distinction between the beautiful and the ugly, the distinguished and the vulgar is linked to the economic and social conditions that such judgments arise from and originate in. Even in food, the distinction between quality and quantity, form, and substance corresponds to the opposition between the taste of necessity of the working class, and the taste of the liberty of luxury that is related to a life of ease.

In organizations, the willingness of agents is influenced by the structure of the organization through habitus, and is defined as "socially constituted systems of rational and motivating structures” [14]. From the definition of habitus, rationality itself becomes socially constituted; therefore, less rational than social; and, therefore, worldly. From this definition, the theory of practice criticizes the theory of rationality, especially the way in which eco-nomics relies on rationality, and especially the rationality concept that is used in economics. Indeed, this rationality tends to ignore the history of agents [23]. Through the collective dimension, the forgotten dimension of Goffman’s presentation of self finally reap-pears: history. This history may appear to be different from Heidegger’s historicity because of its social dimension. However, in this view, the past influences the present and the present is made of the past. The past tends to be reproduced by actors even if they are not conscious of this reproduction. Although there is no Hegelian "spirit” of history, history influences actors through its existence.

The link between social capital and habitus is that the existence of a connection network must be maintained in order to produce benefits such as symbolic or economic capital. Social capital repro-duction implies an ongoing sociability that is associated with exchanges. Therefore, while Goffman’s lifeworld of the presentation of self refers to rationality, Bourdieu’s social capital moves toward innerworldliness through the historical dimension of the concept of habitus.

(2) Others. What is the status of others in social capital? Are they considered in terms of instrumentalism or in terms of "being-with”? In his concept of strategy, Bourdieu remains, like Goffman, in a position of instrumentalism rather than moving toward "being-with.” Strategy is defined as a ‘‘practical evaluation of the likelihood of success of a given action in a given situation” [14]. However, such a concept remains opposed to rationality: "pushing aside interpretations in terms of ‘rational choice’ that the ‘reasonable’ character of the situation seems to warrant” [23]. Once again, if moving away from rationality constitutes a progress, the others are only considered through the point of view of distance: "This ongoing dialectic of subjective hopes and objective chances, which is at work throughout the social world, can yield a variety of outcomes ranging from perfect mutual fit (when people come to desire that to which they are objectively destined) to radical disjunction” [23]. Desire seems to fall back at the individual level. The "objective destiny” of desire is once again on the side of mistrust and not mattering to one another. Moreover, strategies are a "feel for the game”: "Far from being posited as such in an explicit, conscious project, the strategies suggested by habitus as ‘feel for the game’ . . . the objectively originated lines of . . .” [23]. After Goffman's reference to game theory, the world becomes a critical concept again. Even if the potential moves of the players are less subjectively than objectively influenced by history and social context, such a lifeworld considers others in the mode of passing one another and being initially unrelated to others. Such a view is reinforced by the "objective chances”; "[Social strategies are] the internalization of objective chances in the form of subjective hopes and mental schemata” (p. 130, footnote) and "the relationship between dispositions and conditions” (p. 130, footnote). One of the main strategies, according to Bourdieu, is to increase not only economic capital but also social capital, because it may be converted in the long run into economic capital.

Therefore, social capital and strategies are linked through the network of relationships. This network results in investment strategies such as establishing and maintaining social relation-ships. Due to these strategies, Bourdieu's social capital cannot be consistent with Heidegger's "being-with,” and remains within a consideration of others that is characterized by instrumentalism.

4.2.2. Social media and Bourdieu's social capital

Empirical studies have confirmed the importance of strategy in micro-blogging—that is, strategically deciding what to post, what to share, and whom to share with on an open platform where the message has the potential to go viral across the network. These strategies play a critical role in the management of this image of the self, or presentation of the self. In a strategic use of micro-blogging, the posting of content on social media becomes a method of accruing social capital from others in the network and from the metrics and data that comprise the network itself [25]. Online social capital is distinct from offline social capital because of the wide range of people that can be reached instantly online [26]. Online social capital can be considered as a subset of social capital [26]. In this use of social media, the character of use is instrumental, operationalizing a set of objectives for use, into a pattern of use, which corresponds to a strategy for use. For example, academics are noted for their strategic use of social media to build their own image as an academic among the community of academics on social media [27]. This manner of micro-blogging paradigmatically belongs to the field of representational computing, as both the purpose and character of use are instrumental in the pursuit of social capital.

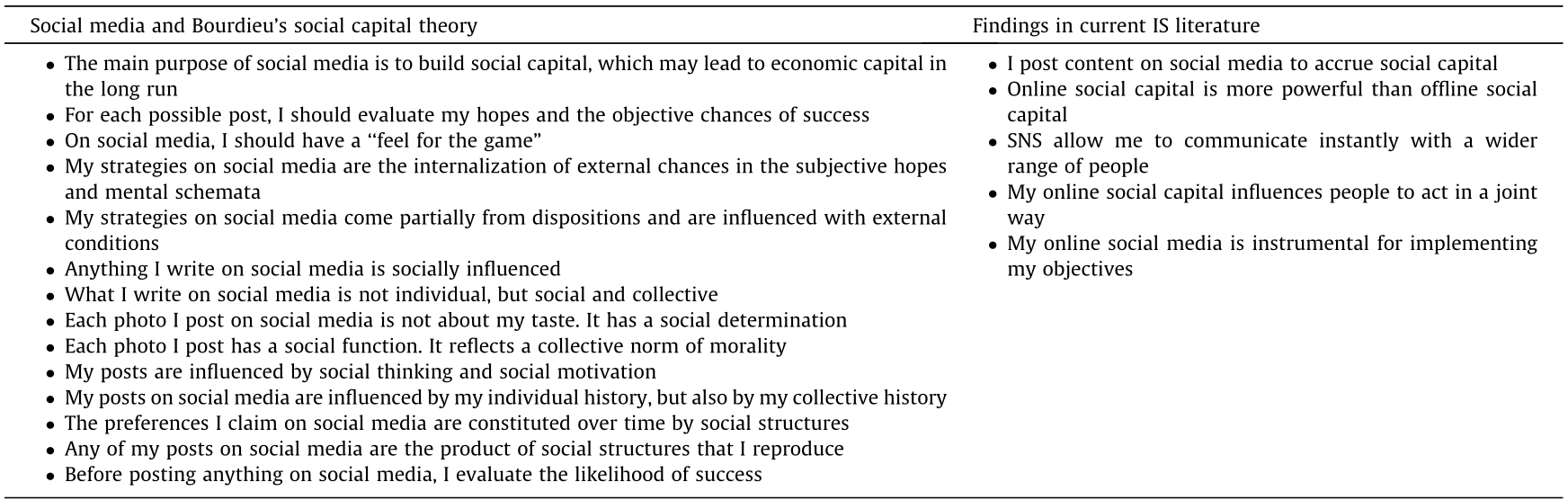

A comparison between Bourdieu’s theory of social capital and empirical findings regarding social media use is provided in Table 2.

《Table 2》

Table 2 Bourdieu's social capital theory compared with findings in IS literature.

《4.3. Social media and Sartre’s existential project》

4.3. Social media and Sartre’s existential project

4.3.1. Sartre’s existential project

Sartre's existentialism has been suggested as a sociological paradigm by Burrell and Morgan [28]. Yoo [29] introduced an existential dimension through experience: "Experience is an essential aspect of our existential struggle. It is our experiences that shape our identity, ideals, and worldview” [29]. Existentialism may definitely be introduced as an archetype of social media use through Sartre's existential project. What assumptions does this theory carry regarding the lifeworld and the status of others?

(1) Lifeworld. What kind of lifeworld does the existential project assume? First, a clear description of what an existential project entails is needed. According to Sartre, behind each human, we need to discover a unity of his or her life. This unity is related to responsibility, and this responsibility should be personal. This unity is also the unity of the person, and the person should be free to perform this unity. In Being and Nothingness [30], Sartre describes the meaning of our being through a project of being. He calls it the "original project,” although here it is called the "existential project.” This project is expressed in each of our observable tendencies. In each tendency and at each moment, the person expresses himself or herself, although from a different angle. Such a unification has been criticized by Bourdieu [14], who claimed that Sartre’s work can be compared with the subjectivity of Descartes. In any case, by the importance it gives to the individual decision and free choice, Sartre’s work carries clear echoes of Cartesian dualism in terms of individual decisions and free choices invoking the specter of the rational agent that is detached from the world and that considers decisions as a "thinking thing” in isolation from the material world. For this reason, Sartre's existential project remains closer to Descartes' rationality than to Heidegger's innerworldliness.

(2)Others. Although Sartre's existentialism has been criticized by Bourdieu [14] and Heidegger as being close to Descartes' duality between the mind and the world, it nevertheless opens a dimension that cannot be found in the work of either Goffman or Bourdieu: "being-with.” Unlike Goffman and Bourdieu, Sartre's Being and Nothingness [30] explores concrete relations with others, and systematically questions the status of the other in such relations. Concrete relations with others are related to the way the "other” looks at "me.” Therefore, Sartre's existential project is consistent with Heidegger's "being-with.” Although this theory is normative, we are not aware of any research in IS that explicitly refers to it. However, is it possible that some of the assumptions of this theory match some of the current empirical findings in social media use, as published in IS?

4.3.2. Social media and Sartre's existential project

Although some of the features of personal representation are clearly shared between micro-blogging sites and SNS, the key difference between the instant flows of micro-blogging and the rooted everydayness of SNS lies in the possibility of constructing coherent histories of presence on SNS. This possibility intermingles with everyday life. In this sense, SNS act as part of the everyday “being-with-others,” in a projection from past relationships to future actions that shapes the present action, as opposed to the reactive, promotional strategies of presentation in micro-blogging. Here, we propose that the everyday use of SNS may be understood through the project of historicizing oneself, which is facilitated by SNS, and that this externalization of memory to SNS can be seen as a continuation in the memorializing of the self in inorganic media that has historically been performed through letters, diaries, and other media-based recordings of the self. The role of SNS in the development of intimate relationships and inter-personal relationships among young people can be understood as an extension of the everyday project of a unity of the self and "himself” or "herself” that is facilitated by SNS; for example, SNS are used for individual customization [31]. Young people have use SNS for experimenting or finding justifications related to diverse aspects of their identity, including sexual, cultural, or ethnic characteristics [32–34]. SNS may also be used for claiming an ethic identity or a cultural identity [35].

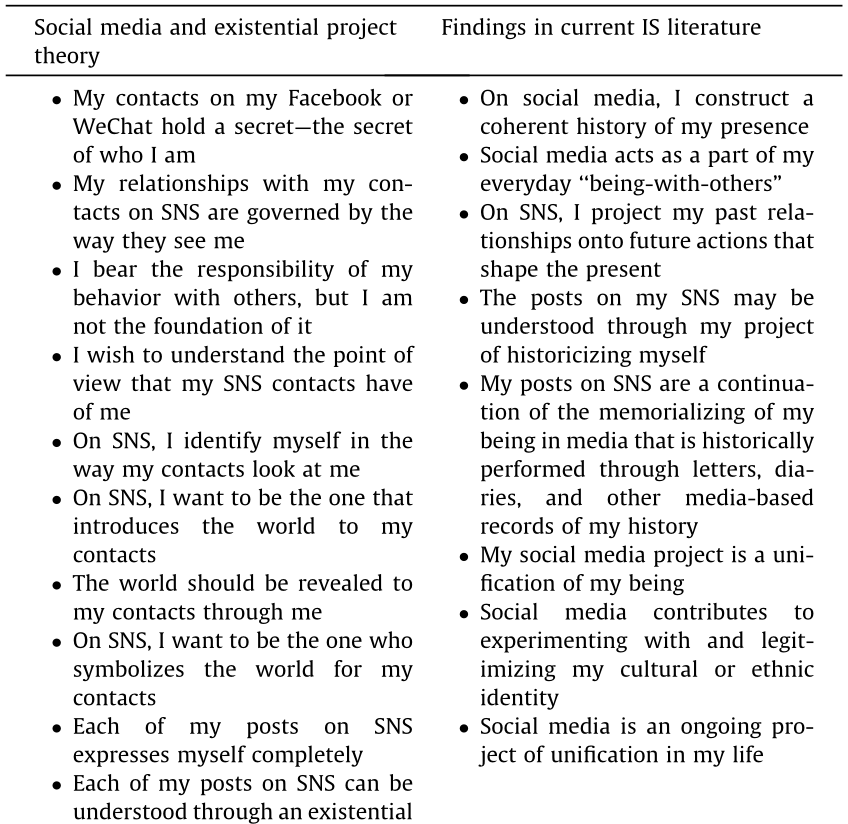

A comparison between Sartre’s theory of the existential project and empirical findings regarding social media use as published in IS literature is provided in Table 3.

《Table 3》

Table 3 Sartre's existential project theory compared with findings in IS literature.

《4.4. Social media and Heidegger's "shared-world”》

4.4. Social media and Heidegger's "shared-world”

4.4.1. Heidegger's "shared-world”

Heidegger has been introduced by Yoo [29] as one of the main references for understanding experiential computing. Because of his aforementioned opposition to Descartes’ rationality, the positioning of Heidegger’s lifeworld toward the "being-in-the-world” that he himself established can be considered as an expected result. In the same respect, Heidegger's critique of instrumentalism locates his theory on the side of "being-with.” However, what does Heidegger’s theory of the shared-world” mean, precisely, and how does it apply to social media use? Because of the importance of others in Heidegger’s theory of the "shared-world,” this section starts by introducing the status of others before describing the lifeworld.

(1) Others. According to Heidegger, our being-in-the-world may be characterized by taking care and by concern for others. Everything I do and everything I think is a reference to my parents, my friends, and/or the love of my life, even if they are not present and even if they have passed away. The meaning of what I do is to show how much I care for them, because they used to care for me so much—like my parents when I was a child, or like my friends who were there for me when I needed them. Such a care may also be expressed in the future by the way I care for my child, or by the way I care for someone I do not know, simply because we are all humans and because humanity is not a fact of nature but a value that is built by our deeds [36]. This is what Heidegger calls the ‘‘shared-world” (in German, MitWelt, which is literally ‘‘with-world”). Therefore, the ‘‘shared-world” moves away from instrumentalism and toward ‘‘being-with.”

(2) Lifeworld. In the perspective of the ‘‘shared-world,” there is no objective presence of objects, unlike in Descartes’ rationality. In ‘‘being-with” and being toward others, there is a relation from one being to another. We ‘‘see through them.” These others are already disclosed in their own being. This previously constituted disclosed-ness of others, together with ‘‘being-with,” helps to constitute innerworldliness. The understanding of others already lies in the understanding of our being because being is ‘‘being-with.” This makes it possible for our being, as an existing being-in-the-world, to be related to beings and to be understood by those it encounters in the world as well as to itself in existing. Therefore, the ‘‘shared-world” moves away from rationality and toward innerworldliness. In what respect can such a normative view contribute to the interpretation of some findings regarding social media use, as published in IS research?

4.4.2. Social media and Heidegger's "shared-world”

Some recent empirical findings on SNS may be related to Heidegger's "shared-world,” such as findings about connectedness or belonging [33]. People are attracted by SNS because of experiences related to others who use such spaces [37]. As Yoo argues, this kind of community and coexistence are not accomplished through a reduction of the complexity of being down to a flattened, emaciated form; rather, they are a facet of the transformation of natural phenomena into digital phenomena that is the key characteristic of digital media. This transformation or remediation does not preserve the original entity; however, the possibility of conducting interpersonal affairs through these channels is just another way of "being-with.” "The current form of associations among individuals that exist in these social network sites can be expanded in several different ways. Currently, most popular social network sites use friendship networks in order to build associations among users” [29].

Historicity is also an aspect of social media use; for example, when using Facebook, the behavior of users can be related to both their past and their future projects. The past appears in Facebook status updates; the present is seen in terms of what is going on; and the future appears through the intentions of the user or through a user’s continuous use of Facebook [25]. SNS use by millennials may be related to this interpretation. Indeed, SNS are contributing to identity expression and sociability in a peer-based and critical way [38]. SNS help young people who come to a university from high school to maintain their previous high school friends and develop new friends at the university, especially those who are less satisfied with the university or who have a low level of self-esteem [26]. Indeed, SNS are often used to maintain existing relationships with friends [39], strengthen young people’s relationships with existing friends [40], or develop intimate relationships [41]. SNS contribute to consolidating identities [41–43].

The role of SNS in the everyday life of millennials is also related to the maintenance of existing friend relationships in the real world. Indeed, compared with real-world relationships, relation-ships that only occur on SNS are not as strong [44]. However, in the case of marginalized or isolated young people, relationships developed on SNS contribute to socialization; for example, this applies to those who suffer from a disability or chronic diseases [45,46]. SNS also contribute to the formation of collective identity in new forms, and create a sense of belonging to a community that is broader than the one in the real world [34,46].

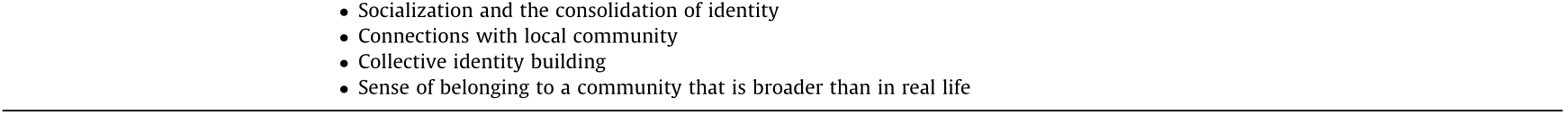

A comparison between Heidegger’s theory of the ‘‘shared-world” applied to SNS and empirical findings regarding social media use as published in IS literature is provided in Table 4.

《Table 4 》

Table 4 Heidegger's "shared-world” theory compared with findings in IS literature.

《5. Conclusion》

5. Conclusion

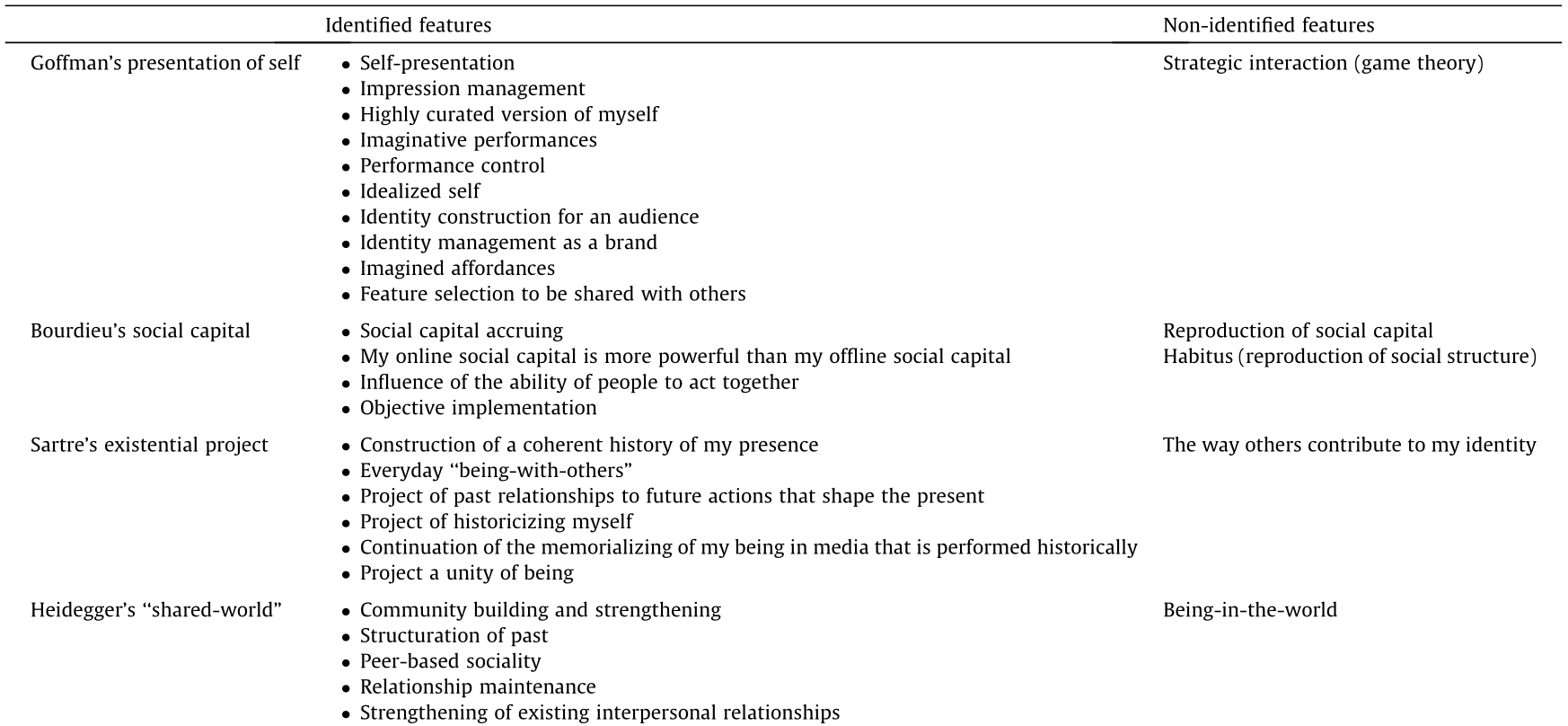

In conclusion, this paper suggests a theoretical framework describing the use of social media relying on Heidegger’s phenomenology that may be referred to as ‘‘phenomenological computing.” This framework allows four archetypal theories to be integrated into the new theoretical perspective. Some of the concepts extrapolated from the four archetypal theories were con-firmed by empirical findings regarding social media as published in IS literature, while others do not match any findings. An abstract of the comparison of concepts related to the four theories and the empirical findings in IS literature regarding social media is provided in Table 5.

《Table 5》

Table 5

Comparison of concepts related to the four theories and empirical findings regarding social media use in IS research.

The features extrapolated from the theories that do not match current findings are Goffman’s strategic interaction (game theory), Bourdieu’s reproduction of social capital and reproduction of social structure ("habitus”), Sartre’s gaze of others that contributes to our identity, and Heidegger’s being-in-the-world. Such a gap may be understood by the fact that most of these concepts were simply not included as observable phenomena in the studies, and therefore may have been neglected because of a methodological theoretical lens.

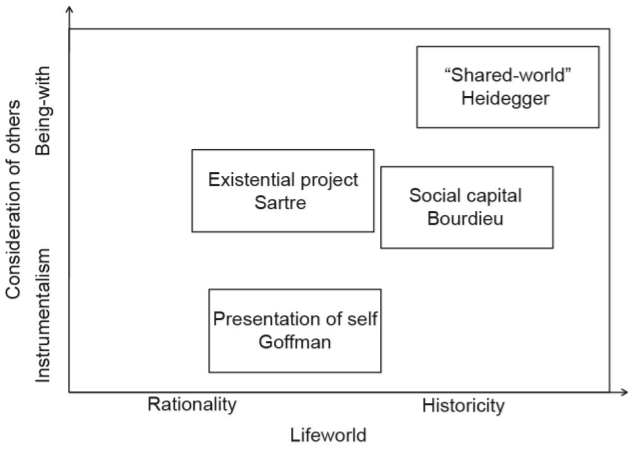

An important finding is that no IS publications regarding social media relying on Goffman or Bourdieu includes a discussion about the contingency of these theories. Therefore, they fall into universalism. Indeed, applying the presentation of self to private life may be arguable, considering that Goffman’s book is related to work situations. Indeed, the intention of Goffman is to describe situations "organized within the physical confines of a building or a plant” (preface). The examples Goffman provides are of a salesman, a waitress, a teacher, an asylum attendant, a doctor, a gas station attendant, or a hotel manager. Therefore, as Goffman’s symbolic interactionism has been built for a work context, it may have little relevance to an understanding of our personal life.

Bourdieu’s theory of social capital is nearly in an opposite situation, compared with Goffman. While Goffman’s presentation of self was written for a work environment, Bourdieu introduces social capital along with cultural capital and symbolic capital in realms other than economics. For example, social capital is dis-cussed for diverse groups in the social world such as a family, class, tribe, school, party, clan or club. The point is that although these kinds of capitals are distinct from economic capital, they are all convertible in the long run into economic capital. Bourdieu’s theory of social capital has been discussed for two decades in management [47]; however, its application to the work environment in IS has been limited to a few studies [48–50] and occurs even less in enterprise social network research.

Although Heidegger’s phenomenology has been introduced as a preferred method for IS research [51], Sartre’s existentialism has been introduced as a sociological paradigm, along with Habermas’ theory of communicative action, by Burrell and Morgan [28]. However, to our knowledge, neither Heidegger’s concept of "shared-world” nor Sartre’s concept of "existential project” has been used in IS research on describing social media. The point is that these two philosophies were written for everyday life, and therefore may be more relevant for describing the personal use of social media than the works of Goffman or Bourdieu. Indeed, while Bourdieu’s theory refers to any group in the social world, it still remains within the perspective of conversion into economic capital, and thus remains in an economic perspective rather than in a perspective of everyday life.

Along with this contextual inquiry, another contingency should be discussed here: the intention of social media uses. Elaborating on Boyd [21], three intentions may be distinguished: open, semi-open, and closed intention of use. For example, an open intention of social media use may correspond to micro-blogs because postings are mostly open to anyone; that is, anyone can read a post and repost it, and anyone can connect to anyone without permission. On the other hand, a semi-open intention of use may be found when we protect our micro-blog account. Finally, a closed intention of use may be found in SNS such as WeChat or Facebook. Indeed, these SNS require users to limit the audience of their posts. To be connected, a person needs the other’s agreement first. Although closed-use intention may be more relevant to a personal environment, open-use intention may correspond to a work environment. However, this distinction is challenged by companies that tend to encourage their employees to discuss not only work matters but also personal matters with colleagues using SNS, in order to enhance cooperation [52]. This matching of theories and context is purely speculative here; however, an outline of a contingency model that may guide future research is provided in Table 6.

《Table 6》

Table 6 Speculative contingency model of the four theories.

The contributions of this research are as follows:

- In order to compare different theories regarding social media, philosophical foundations based on Heidegger’s phenomenology were proposed to elaborate a framework of lifeworld and consideration of others.

- Four different theories were compared regarding the use of social media: Goffman’s presentation of the self, Bourdieu’s theory of social capital, Sartre’s existential project, and Heidegger’s "shared-world”.

- The conceptual implications of the four theories were compared with the findings in the literature related to social media.

- In order to suggest a context of relevance for each of these theories, a contingency model was suggested.

Although many of the concepts related to these theories match findings in IS research about social media, some of these concepts have not investigated yet, creating new research opportunities. In addition, a contingency model regarding the relevance of the theories that were identified encompasses the environment and the intention of use. The environment may be related to work or to personal life, and the intention of use may be open, semi-open, or closed. Although the theories of Goffman and Bourdieu were developed in an economic context, they have been applied to a personal context and to a closed intention of social media use without a discussion of their relevance. Such an extrapolation is question-able. Indeed, new contexts require new theories. For describing the contexts of a personal environment and a closed intention to use social media, compared to Goffman and Bourdieu, the theories of Sartre and Heidegger may be more relevant because they were not written from an economic perspective but are philosophies of everyday life.

《Acknowledgements》

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Key Programs of National Natural Science Foundation of China (71231002), Major Projects of National Social Science Foundation of China (16ZDA055), National Natural Science Foundation of China (91546121 and U1636215), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFB0803300).

《Compliance with ethics guidelines》

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Jiayin Qi, Emmanuel Monod, Binxing Fang, and Shichang Deng declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号