《1. Introduction》

1. Introduction

Water-triggered materials are currently drawing increasing attentions in various areas, such as transient electronics [1], smart materials [2], soft actuators [3], and energy generation [4,5]. Given the ubiquity of water, such materials generally have advantages such as easy operation, broad responsively, low cost, and environmental friendliness [5]. One of the most important applications of water-triggered materials is for shape memory actuators. Cheng et al. [6] had ever developed a fiber based on graphene, which can twist under different degrees of moisture and can act as a motor in a moist environment. Yang et al. [7] revealed a shape memory polymer that is sensitive to water and realizes reversible deformation under high and low water content. Shape memory polymers that can be triggered due to addition of water have also been reported [8]. However, restricted by the nature of polymers, these materials often request a large amount of water or take a long reaction time, and their mechanical properties may not meet the requirements, especially under extreme conditions. Moreover, the preparation processes usually appear rather complicated, and the fabricated materials are not easy to preserve in an ambient environment.

Liquid metal (LM), especially room-temperature LM based on gallium (Ga) alloys, is now of great interest in many areas such as three-dimensional (3D) printing [9,10], chip cooling [11,12], and flexible electronics [13–15], owing to its remarkable thermal and electrical properties. The liquid nature of these metals makes it possible to combine them with multiple particles of different species and sizes, which vastly improves the metal’s physical and chemical properties to better meet the requirements in various application scenarios. For example, researchers have loaded eutectic gallium–indium (eGaIn) alloys with nickel particles to enhance its adhesion and printing capability, and with copper particles to obtain better thermal conductivity [16,17]. Iron particles were also added into eGaIn, resulting in magnetic and self-expansive properties not owned by the original eGaIn otherwise [18]. It is worth noting that a special reaction would occur between eGaIn and aluminum in alkane solutions, in which the LM displays very conventional self-driven behavior [19]. Hydrogen production based on the Al-eGaIn in water has also been discovered [20]. The mechanism of the surface reaction based on the eGaIn system has also been discussed [21,22]. However, multiple challenges remain to be addressed for Al-eGaIn-based systems, such as gas production, thermal performance, reaction rate, and working efficiency.

In this study, we came up with a new kind of Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn material, which shows excellent thermal and gas production properties under the actuation of deionized (DI) water. Once triggered, the temperature rise of 1 mL of Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn increased to more than 40 °C in just several seconds, with the heat mostly being generated in the location where the water was applied, indicating potential for accurate heating. The gas production capability was also measured, including the generation rate and final volume of gas produced. It was demonstrated that the Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn can produce twice as much as its original volume of hydrogen gas via a pretty rapid rate. The recyclability and degradation behavior were also evaluated, revealing that Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn is a reusable and degradable material. Based on these results, we designed a novel, convenient, comfortable, and reliable fixation patch which can serve as a smart bandage in first aid applications using Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn and BiInSn alloy. Benefiting from the selfexpansion property of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn in the inner layer, this device is able to realize high adaptability and can firmly attach to various surfaces, including the surface of the human body. Furthermore, we developed a prototype of a watertriggered rolling robot consisting of a soft shell made of EcoFlex and an inner core filled with Al-NaOH-eGaIn. Once encountered with water, the device would pump up into a sphere, making further motions such as rolling and bouncing possible. This study provides a new material for thermal and pneumatic actuators, which can be used as a thermal trigger for temperature-related phase transition materials and as a pneumatic trigger for the motion regulation of specific structures in soft robotics. It holds big potential for applications in wearable motion-aided devices and exoskeleton systems, even in soft robotics.

《2. Materials and methods》

2. Materials and methods

《2.1. Preparation of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn》

2.1. Preparation of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn

For the raw material, eGaIn was selected, which was made by uniformly mixing molten pure Ga and indium (In) at 120 °C according to the weight ratio 75.5:24.5. Next, aluminum (Al) micro-powder (200 mesh count) was added according to the weight ratio 1:20. A certain amount of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) powder ground by mortar was then added and mixed uniformly (2.5 wt%). The mixture was mixed by a stirring paddle until it became uniform, resulting in a final product that appears as a gel-like semifluid with a dark silver luster. DI water was used as the trigger solution. The fabrication and trigger process is shown in Fig. 1(a) and Appendix A. Supplementary Video.

For comparison, Al-eGaIn and NaOH-eGaIn were prepared. The mass ratio of Al and eGaIn in Al-eGaIn is 1:20, and the NaOH-eGaIn was prepared according to the weight ratio of 1:40. The raw materials were the same as mentioned above.

《Fig. 1》

Fig. 1. Evaluation of the heat performance of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. (a) Schematic diagram of the preparation and trigger process of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. (b) Real and infrared images of Al-composited eGaIn and Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn triggered by DI water. The volume of the metal mixture and water applied was 1 and 0.5 mL, respectively. (c) Relationship between temperature rise (△T) and time. Inset is the expansion ratio of the mixture changed along with the time after triggering. The volume of water applied was 0.5 mL. (d) Relationship between the temperature rise and the time to reach the highest temperature as the amount of water increased.

《2.2. Heating performance measurements》

2.2. Heating performance measurements

To evaluate the heating performance, 1 mL of NaOH-eGaIn, Alcomposited-eGaIn, and Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn were triggered by a certain amount of water. The temperature change during the whole process was measured by a T-type thermocouple and recorded by Agilent 34970A (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). The sample internal was set as 5 ms. In addition, temperature distribution during the reaction was monitored by an infrared camera (SC620, FLIR Systems Inc., USA). FLIR software was used for image analysis and post-processing. The heat diffusivity of pure eGaIn and Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn from 30 to 150 °C was measured by LFA467 HyperFlash (NETZSCH, Germany).

《2.3. Expansion behavior evaluation》

2.3. Expansion behavior evaluation

The expansion behavior was evaluated using the volume of the metal itself and gas produced. The measuring system consisted of a 5 mL graduated cylinder and a 2 mL injector. The former was used to measure the volume of metal, while the latter was applied to measure the gas produced. The system was connected by silicon tubes and sealed by Vaseline to ensure its gas tightness. To begin the process, a certain amount of water was added into the cylinder prefilled with 1 mL Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. The plunger of the injector was pushed by the pressure caused by the gas generated. The final volume of gas produced and the metal in the cylinder after the finalized reaction were recorded. The time required to generate 1 mL of gas was recorded as an evaluation factor of the reaction rate of gas production.

《2.4. Element analysis》

2.4. Element analysis

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used for element analysis to further clarify the reaction mechanism. The Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn and reaction products were analyzed separately.

《2.5. Design of the liquid metal-based smart bandage》

2.5. Design of the liquid metal-based smart bandage

Based on the thermal and expansion behavior of Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn, a smart water-triggered bandage was designed. The bandage was fabricated as a double-layer structure. Its internal side was composed of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn and the material of outer side could be chosen as low-melting alloy such as BiInSn (melting point: 58.8 °C [23]) or other suitable Ga-based alloys. Polyethylene (PE) valve bags with the dimensions of 10 mm × 7 mm were used as the package. The thickness of the Ga layer and the Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn layer was 1.5 and 0.5 mm, respectively. These two layers were bonded by a thin layer of glass–rubber. A certain amount of water was injected at the desired position to trigger the reaction, melting the metal layer outside. Then the softened device was applied on a body part that needed fixation such as joint with the BiInSn layer on the outside, and continual pressure was put on to ensure its maximal contact to the surface. Ice bags or cold water could be used to cool the patch, accelerating the re-solidification process until the bandage became completely fixed.

《2.6. Design of water-triggered expansion spherical robot》

2.6. Design of water-triggered expansion spherical robot

The fabrication process of the spherical robot is displayed in Appendix A. Fig. S1. The sphere consisted of two parts: a shell made of EcoFlex 0050 and an inner core composed of Al-NaOHeGaIn. The shell was made using two semi-spherical molds with a diameter of 30 mm. The average thickness of the soft shell was 1.2 mm. The Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn was kept in a notched EcoFlex film to keep it in a fixed location while ensuring the release of the gas produced. After the EcoFlex was fully cured, an injector was adopted to extract the extra air inside.

《3. Results and discussion》

3. Results and discussion

《3.1. Performance of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn》

3.1. Performance of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn

3.1.1. Heating performance

The water-triggered heating behavior is one of the core functions of the present Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn material. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the mixture immediately reacted with water upon coming into contact. Its volume expanded and the surface was surrounded by a hard shell formed of grey powder. The residual eGaIn was squeezed out from the crack on the outside hull. According to the thermal infrared images, the temperature of the mixture increased rapidly, from 41.7 to 82.0 °C for Al-eGaIn and from 41.6 to 96.3 °C for Al-NaOH-eGaIn, both in 15 s. The heat generation was mainly focused at the center of the metal, while the eGaIn that was squeezed out had a much lower temperature due to its excellent heat conduction.

Fig. 1(c) shows the heating response of Al-eGaIn, Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn, and NaOH-eGaIn, respectively. Unlike the NaOH-eGaIn without Al powder, the Al-composited eGaIn without NaOH reacted with the DI water and rapidly produced a large amount of heat. However, the temperature rise (△T) was less than two-thirds of that with NaOH, indicating excellent heat conduction efficacy by Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. During the heating process, Al-eGaIn and Al-NaOH-eGaIn also exhibited expansion behaviors, which will be further discussed in the next section. The relationship between the volume of water applied and the temperature rise, as well as the response time of Al-NaOH-eGaIn per milliliter, is depicted in Fig. 1(d), which shows that even a tiny amount of water (0.01 mL) would cause an evident temperature rise of the Al-NaOH-eGaIn in a short time. As the amount of water applied increased, the maximum temperature rise could reach around 35 °C when 0.08 mL water was added, and then decreased. The decrease in temperature is probably caused by the evaporation of water and heat loss during the heating process, which may consume part of the heat generated. The time from being triggered to reaching the highest temperature always took less than 25 s, and ranged from 8 s when 0.01 mL water was added to 21 s when 0.12 mL water was added. Clearly, this time response is quick enough for most uses.

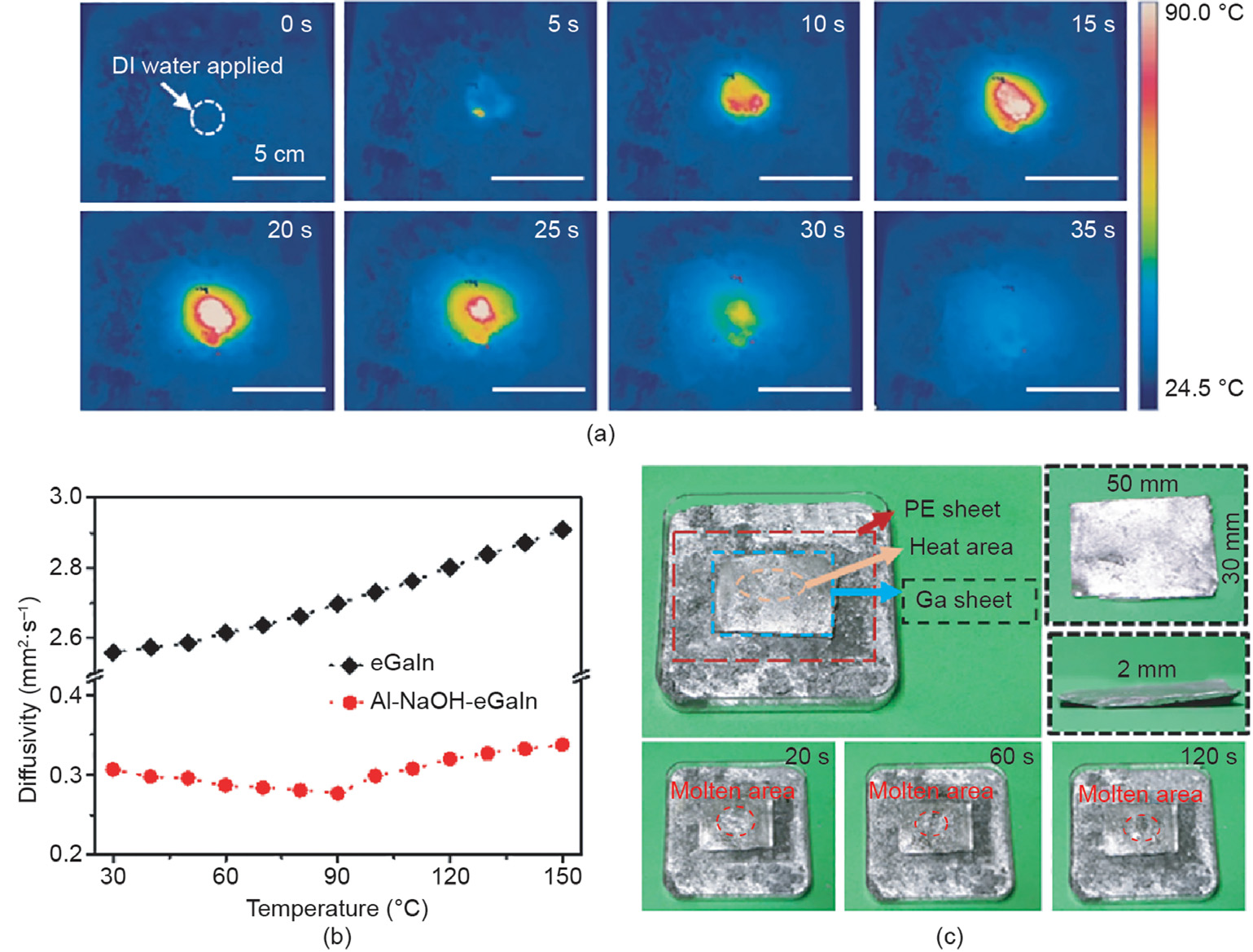

In addition to the quick heating phenomenon, the local response property of the material is worth noticing, as it permits accurate heating. Fig. 2(a) shows the temperature distribution of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn triggered at a certain point. During the whole process, the highest temperature occurred at the trigger point and slightly spread to the neighboring area, indicating the potential of an accurate calefaction source. The thermal diffusivity of eGaIn and Al-NaOH-eGaIn at different temperatures are provided in Fig. 2(b). Compared with pure eGaIn, eGaIn mixed with Al and NaOH had a lower diffusivity of 0.31 mm2 ·s-1 —about 1/8 that of pure eGaIn—which further proves the above assumption. This is mainly due to the addition of Al powder, which may introduce tiny gaps between the metal and grains, obstructing heat diffusion inside the material.

In addition to measurements, a heat diffusivity test was performed to evaluate the heating performance of the material. As shown in Fig. 2(c), a 2 mm thick Ga sheet was placed on a PE sheet above a pool of Al-NaOH-eGaIn. A volume of 1 mL DI water was added on the center of the bottom mixture. After 20 s, a small molten area with a diameter of 2 mm appeared at the triggered area and gradually expanded to 4 mm after 60 s. Finally, the molten area stabilized at a 5 mm circle after 2 min. The remainder of the Ga sheet remained in the solid state. This phenomenon reveals one possible method for using Al-NaOH-eGaIn—namely, as a thermal actuator to accurately regulate the stiffness of a series of low-melting metals such as BiInSn and BiInSnZn by changing their existing status.

《Fig. 2》

Fig. 2. Local heating performance of Al-NaOH-eGaIn. (a) Infrared images of the triggered Al-NaOH-eGaIn. 1 mL water was applied at a certain trigger point. (b) Heat diffusivity of pure eGaIn and Al-NaOH-eGaIn from 30 to 150 °C. (c) Partial melting of a Ga sheet by triggered Al-NaOH-eGaIn. A PE sheet was used to avoid direct contact between the Ga sheet and the triggered Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. The Ga sheet was 50 mm × 30 mm × 2 mm, and 1 mL DI water was applied at the center of the Al-NaOH-eGaIn material. The orange circle in the three bottom images indicates the area of the molten Ga.

3.1.2. Gas generation and expansion properties

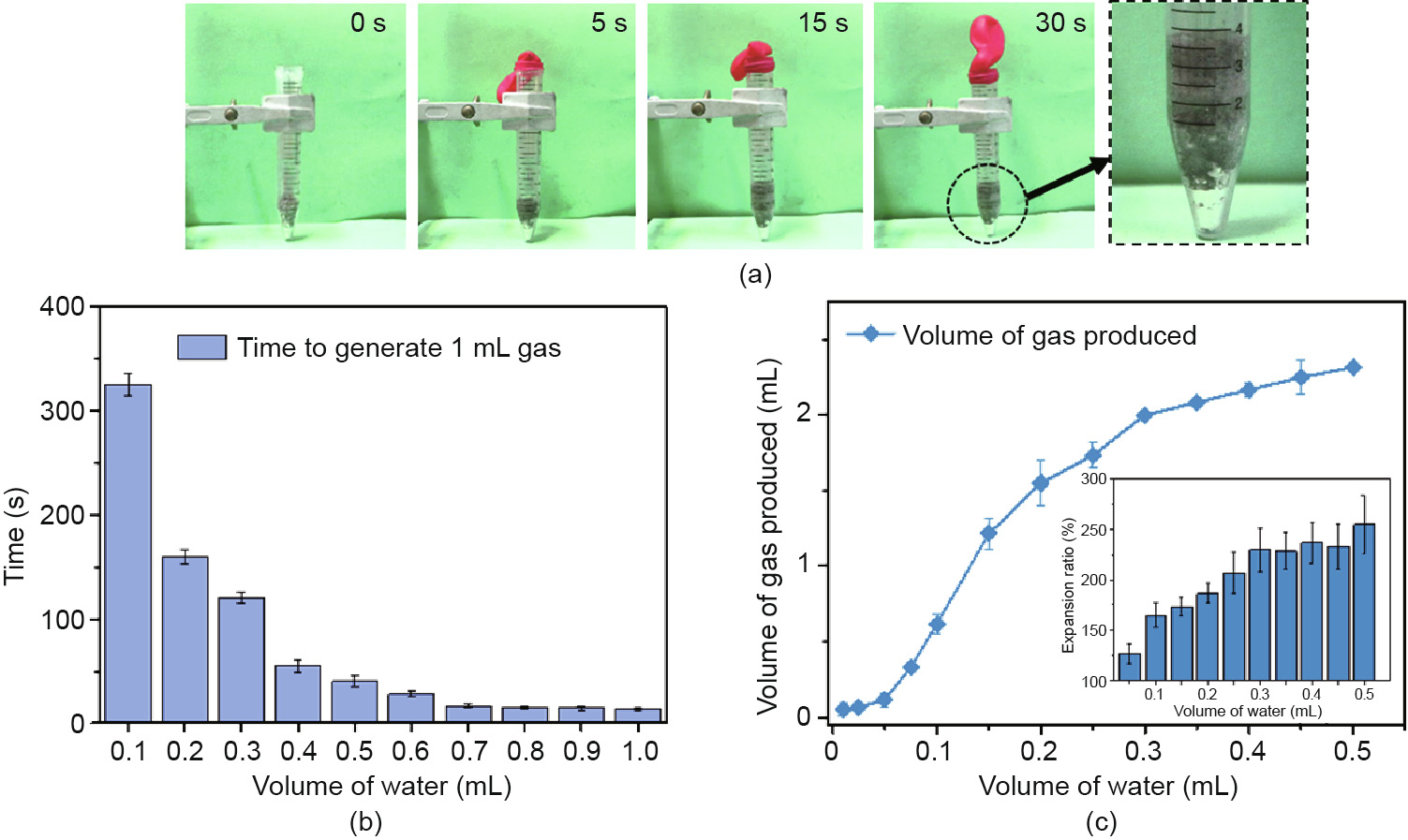

In addition to the production of heat after the application of water, Al-NaOH-eGaIn exhibited the phenomena of volume expansion and gas generation. As shown in Fig. 3(a), a substantial amount of gas was produced after the addition of water, which is consisted of H2 and the expanded air under heating conditions, while the mixture expanded to about two times its original volume in 30 s. As shown in the detailed photo, the mixture was split into two layers after the reaction: a residue of pure metal at the bottom and a black porous structure on top. Fig. 3(b) summarizes the relationship between the gas production rate and the volume of water applied. The time taken to generate 1 mL of gas per milliliter of AlNaOH-eGaIn was in a reverse ratio to the volume of water added, from 325 s with 0.1 mL of water added, to only 11 s with 1 mL of water added. Fig. 3(c) shows the quantity of gas production related to the volume of water added. The final volume of gas generated has a positive correlation with the volume of water added and tends to level off when the water reaches 0.4 mL. This is related to the extent of the reaction, which is determined by the volume of water added. Fig. 3(c) also shows the expansion ratio of the mixture itself in the inset. The mixture expanded from 125% to 250% of its original volume according to the amount of water added, indicating the potential for self-expansion in many applications. Based on these results, Al-NaOH-eGaIn could be used as a pneumatic actuator and as potential hydrogen production material.

《Fig. 3》

Fig. 3. Gas generation of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. (a) Gas generation process of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. The volume of treated eGaIn and water added is 2 and 1 mL, respectively. (b) Time for 1 mL Al-NaOH-eGaIn to generate 1 mL gas along with the volume of water added. (c) Relationship between the amount of gas produced and the volume of water added. Inset is the final volume of the metal expanded related to the volume of water added. The volume of initial Al-NaOH-eGaIn is 1 mL.

3.1.3. Reusability and degradation

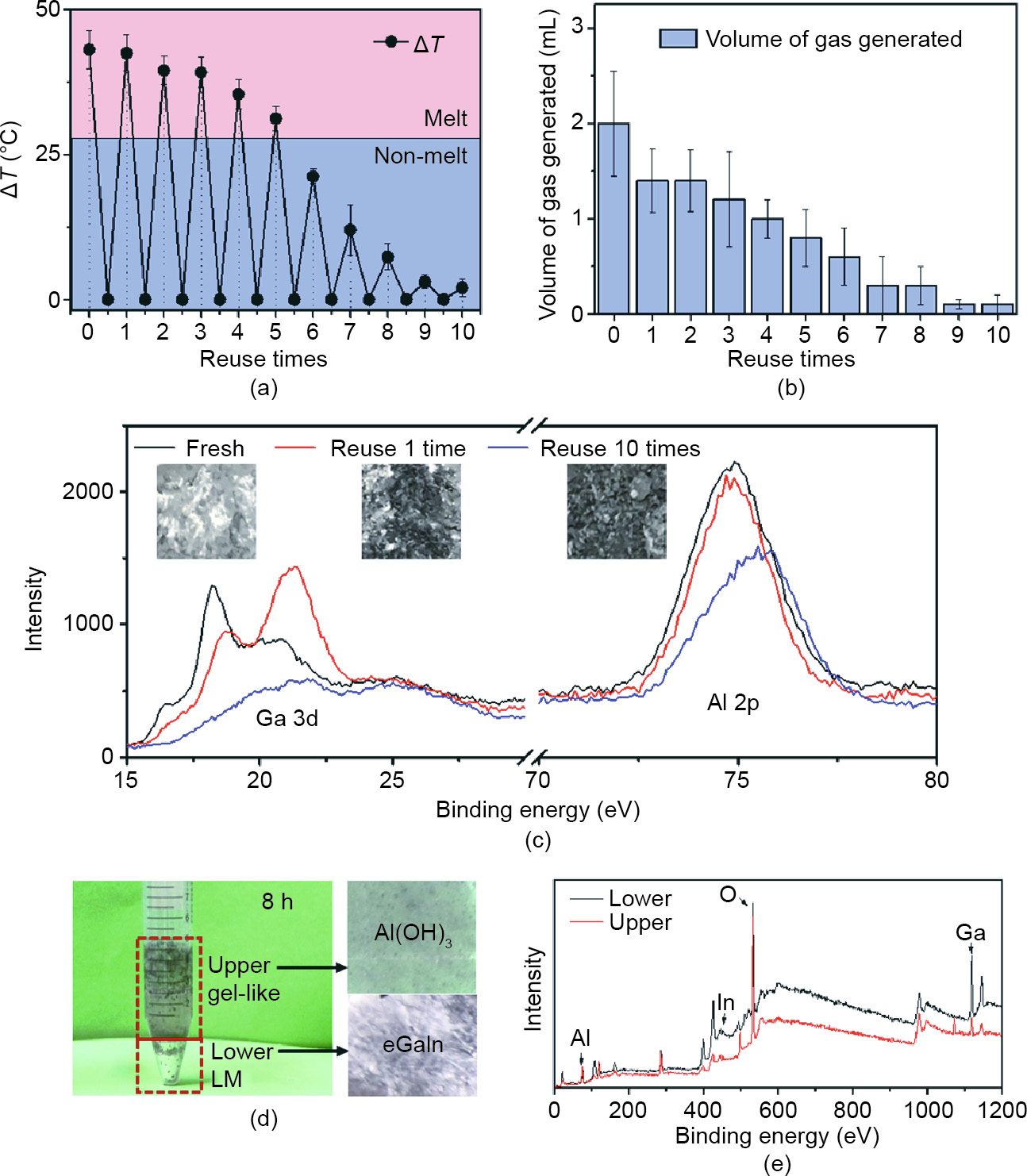

Instead of being immediately disposable, Al-NaOH-eGaIn has the ability to be re-triggered several times. Fig. 4(a) shows the highest temperature elevations of each re-triggered time. To better understand the meaning of the temperature change, we set the melting point of BiInSn alloys as a reference temperature. AlNaOH-eGaIn could act as a trigger for BiInSn phase transition, leading to a change in stiffness to realize multiple functions. For the first five re-trigger times, the temperature rise gradually decreased from 43 to 31 °C, which was strong enough to completely melt the BiInSn sheet underneath. However, the heat produced was insufficient for complete melting the sixth time. In the following triggering process, the heat produced failed to melt the BiInSn alloy of the outsider layer. Fig. 4(b) illustrates the gas production behavior. Triggered by 0.5 mL DI water, the gas produced each time gradually decreased from 2 mL for the first time to 1 mL for the fourth reuse time, and was finally near zero for the ninth and tenth reuse times. This result indicates the continuous gas production ability of such material, which would permit multiple control methods to regulate the actuation and deformation of the targeted structure. To further classify the changes in the substance during the reaction, Fig. 4(c) shows the XPS results of Al-NaOH-eGaIn after triggering. With an increased triggered time, the mixture became darker and more porous due to reaction, leading to unstable existence of the mixture, reflected in the consumption of Ga and Al in the mixture.

The degradation property of the material is also of great importance for better application and recycling. The original Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn could exist stably in an ambient environment for two weeks or even longer, reducing storage difficulties (Fig. S2). Also, the condition for the degradation of Al-NaOHeGaIn is quite simple: the addition of adequate water. Fig. 4(d) shows the outcome after Al-NaOH-eGaIn was left in excess water for 8 h, and Fig. 4(e) provides element analyses of the top and bottom layers. The final product was separated into two parts: gel-like Al(OH)3 and pure eGaIn alloys. Of these, the eGaIn could be recycled for other uses and the Al(OH)3 could be collected easily for further treatment.

《Fig. 4》

Fig. 4. Reusability and degradation of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. (a) Temperature rise after re-triggering. The volume of the initial Al-NaOH-eGaIn and of the water added each time is 1 mL and 0.1 mL, respectively. The thickness of the BiInSn (melting point ~58.8 °C) beneath is 1 mm. (b) Amount of gas produced related to the reuse times of Al-NaOH-eGaIn. The initial volume of Al-NaOH-eGaIn and of water added each time is 1 and 0.5 mL, respectively. (c) XPS results of Ga and Al in the fresh Al-NaOH-eGaIn, Al-NaOH-eGaIn triggered one time, and Al-NaOH-eGaIn triggered ten times. The inset pictures are the appearance of the sample for each period. (d) Actual photo of Al-NaOHeGaIn after being degraded by excess water after 8 h. The pictures on the right are the appearance of the upper gel-like liquid and the lower LM. (e) XPS results of the upper and lower materials. The red line represents the upper liquid and the black line indicates the lower LM.

《3.2. Reaction mechanism of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn》

3.2. Reaction mechanism of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn

Fig. 5(a) shows a schematic diagram of the mechanism. Once the composites come into contact with water, the NaOH particles dissolve first, providing a liquid reaction environment for the subsequent steps. As a typical amphoteric metal, Al can react with alkali solutions, producing large amounts of heat and hydrogen. The reaction equation involved can be written as Eqs. (1) and (2) [24]:

where  is the enthalpy change under 298 K.

is the enthalpy change under 298 K.

《Fig. 5》

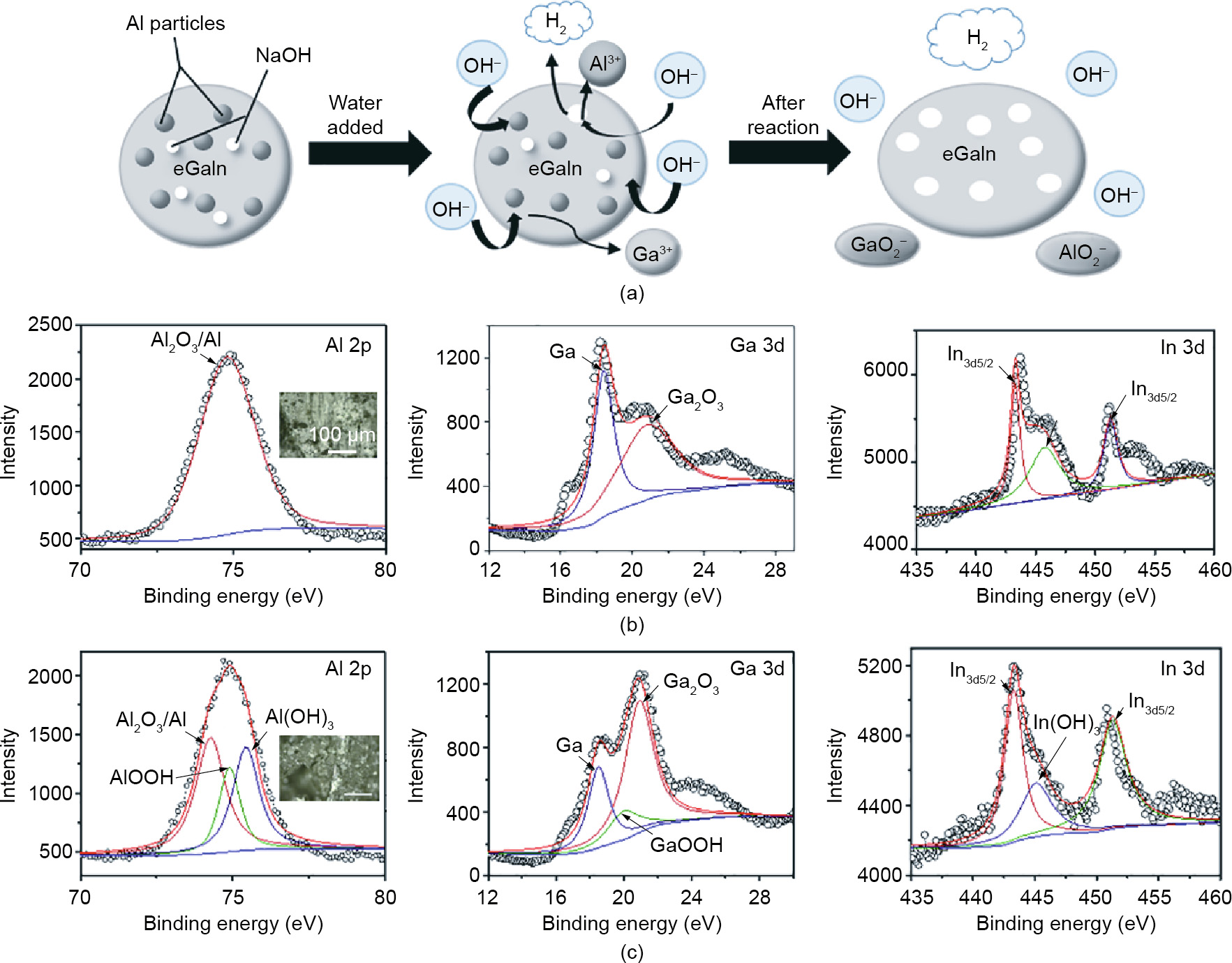

Fig. 5. (a) Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism of Al-NaOH-eGaIn with water. (b) Detailed XPS results of Al, Ga, and In in fresh Al-NaOH-eGaIn. Inset image is the micrograph of the fresh sample. The scale bar is 100 μm. (c) Detailed XPS results for Al, Ga, and In in the reacted Al-NaOH-eGaIn. Inset image is the micrograph of the reacted sample. The scale bar is 100 μm.

Unlike the regular reaction of Al and NaOH, in this case, the LM played an important role in promoting the reaction process. Four experimental groups were compared in the following order: Al powder with NaOH solution, Al powder mixed with NaOH with DI water, Al-composited eGaIn with NaOH solution, and AlNaOH-eGaIn with DI water. Of all of these groups, Al-NaOHeGaIn with water showed the most intense reaction phenomena, including a quick response, a large amount of heat released, and gas production. This can be explained by the primary battery theory. According to the activity order of metals, Al is more active than Ga and In, and acts as the cathode in the Al-eGaIn-NaOH system, while eGaIn is the anode. The reaction equations on electrodes are written as Eqs. (3) and (4):

In this situation, the Al particles, which worked as the cathode, were packed in the eGaIn, transforming the whole mixture into a reaction system. Compared with a conventional primary battery system, Al-NaOH-eGaIn has a larger contacting area here, accelerating the reaction rate. As the reaction continued, the hydrogen produced formed small holes on the surface of the mixture, permitting the permeation of water to the deeper part of metal, resulting in a porous structure and increasing the volume. To provide a better understanding of this reaction process, Figs. 5(b) and (c) show the detailed XPS results of Al, Ga, and In in the solids before and after triggering, which is based on the former XPS results shown in Fig. 4(c). As disclosed by these figures, the oxide content of all these amphoteric metals has decreased, while different basification processes were experienced. The Al powder, which had the largest specific area and high reactivity, became the main participant in the reaction, forming Al(OH)3 and AlOOH. The Ga also participated in the reaction and changed to its oxidation state, resulting in final products of mainly GaOOH and Ga2O3. The In tended to remain in the zero valence state, although a small amount changed to its oxidation state, probably reacted with NaOH, and formed In(OH)3. The gas produced was shown to be hydrogen by a flame test, which further demonstrated the hypothesis. According to the measurements, Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn has a density of 5.0 g·cm-3 , which is slightly lower than that of eGaIn (6.28 g·cm-3 ). Due to additional particles, the viscosity of the metal has been greatly improved, making better attachment on various substrates possible and improving the 3D shaping capacity. Based on these facts, the reaction process could be better controlled and the behavior of devices made from this watertriggered material could be regulated.

《3.3. Representative applications》

3.3. Representative applications

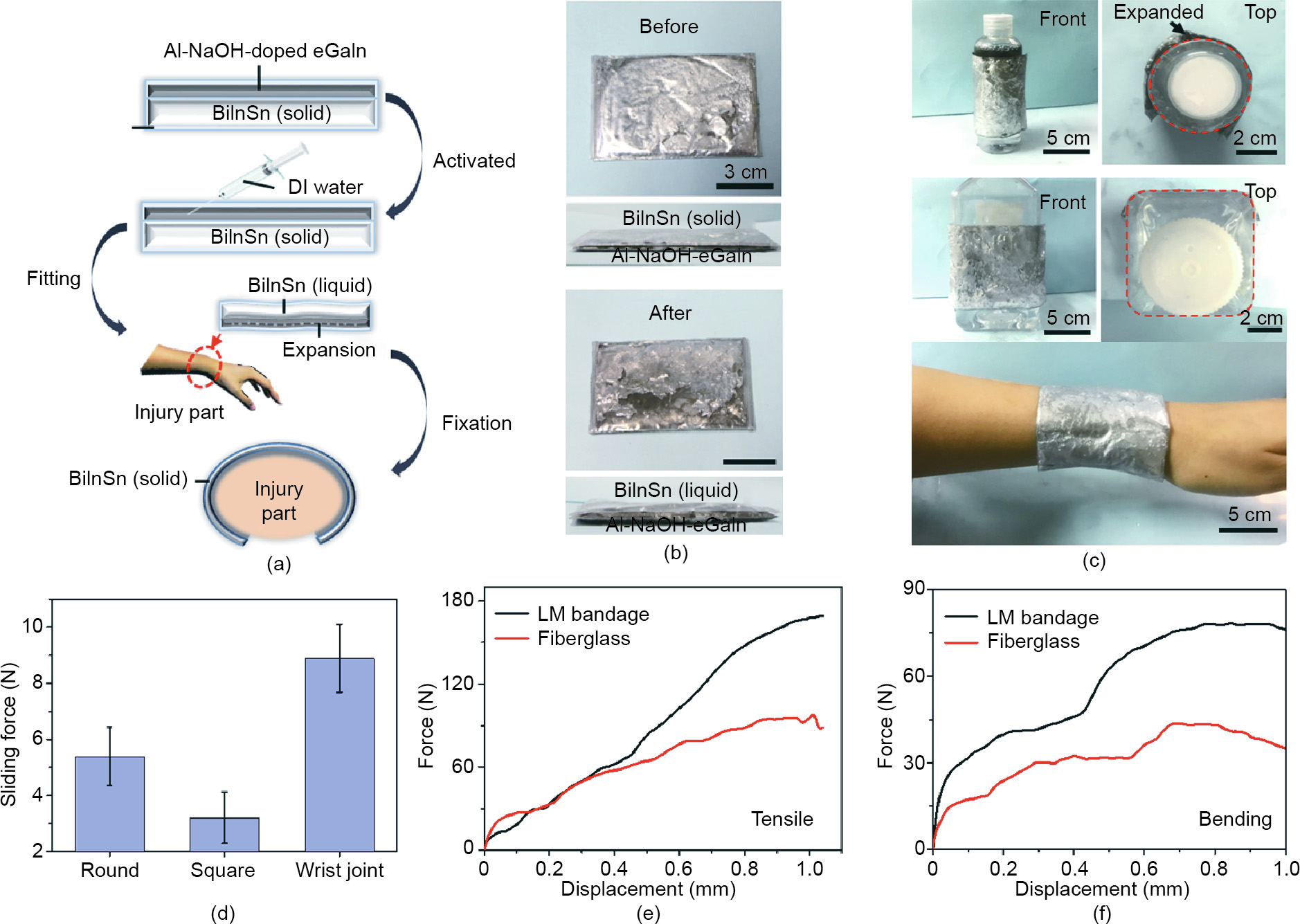

3.3.1. Smart bandage

Aside from gas production, the accurate local heating ability of Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn holds promise for development as a thermal actuator, which could be used to trigger the phase transition process. Combining these two important factors together, we designed a smart bandage system based on four low-melting point metals (such as gallium alloys and bismuth alloys) and Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn, which can be fixed on the human body or can act as a temporary support under emergency situations. The usage of the designed bandage (taken BiInSn as an example) is shown in Fig. 6(a).

The appearance of the double-layer patch is presented in Fig. 6(b). Before being triggered, the patch is maintained in the solid state with a thickness of 2.5 mm. After the injection of DI water, the thickness increases to 5 mm due to the self-expansion and gas production of the Al-NaOH-eGaIn. The generated heat melts the solid metal layer, changing the patch into a shapeable soft state. Fig. 6(c) shows the conformability of one activated bandage on various subjects with different types of sections, including round, square, and the physiological curve of a human wrist joint. The patch shows excellent fitting performance on these surfaces, benefiting from the pneumatic property of the inner Al-NaOHeGaIn layer. From Fig. 6(d), it can be seen that the sample showed the best attachment to the wrist joint—better than that on the PE bottle with a round section and a square section. This is probably related to the profile and material of the target surface. Furthermore, the soft nature of the inner layer causes no constriction or discomfort when applied on the human body. The slight warming caused by the reaction of the inner layer faded naturally in several minutes after application.

《Fig. 6》

Fig. 6. Smart bandage designed with BiInSn and Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn. (a) Usage of the smart bandage based on Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn and BiInSn alloy. (b) Appearance of the bandage before and after triggering. (c) Bandage using Al-NaOH-composite eGaIn as heating agent applied on a cylinder surface, square surface, and human wrist. (d) Sliding force of the bandage applied on a cylinder surface, square surface, and human wrist. Force-displacement curve of the LM bandage and fiberglass under (e) stretching and (f) bending.

We also compared the mechanical property of our bandage with fiberglass, which is a common material used for body fixation in medical applications. The fixation effect is highly related to the stiffness of the fixator. Assuming that the Al-NaOH-composited eGaIn is a liquid whose Young’s modulus can be regarded as zero, then the model can be simplified as a Ga sheet with a thickness of 1.5 mm. According to the formula of the flexural rigidity of a sheet, Eq. (5) is obtained:

where D is the flexural rigidity, E is the Young’s modulus of the material, t is the thickness of the sheet, and μ is the Poisson’s ratio. Loading tests of stretching and bending were performed, and a comparison of the force–displacement relationship of the LM bandage and that of fiberglass is shown in Fig. 6(e). The calculated tensile and bending modulus of this LM bandage are 11.85 MPa and 2.17 GPa, respectively, which are much higher than those of a fiberglass bandage (5.24 MPa and 0.74 GPa, respectively). Furthermore, the application process is shortened from 10 min (fiberglass) to 5 min (LM bandage). An actual loading measurement was also applied to the designed bandage. The sample showed excellent bearing capacity after solidification, especially under a loading of 1.8 kg, demonstrating its reliability and rigidity. When the loading reached around 2 kg, cracks started to occur at the area in contact with the bottom edge of the weights, leading to failure of the structure. This was due to crystallographic defects that occurred during re-solidification because of uneven cooling, which weakened the mechanical performance under the high-load conditions. However, the bandage still satisfied the requirements of fracture fixation in general applications.

To extend the applicability of the device to more specific situations, we came up with a method to assemble the single parts into an overall system. The binding force between two different parts was tested, and the average force required to peel two parts apart was found to be (12.35 ± 2.43) N after the Ga got completely solidified. Failure mainly occurred on the outside package instead of at the joint, demonstrating the reliability of the connection. However, when necessary, these two parts are easy to separate by reheating the Ga layer. This provides a new approach for external fixation methods for first-aid measures and follow-up treatments for bone fracture—and even for wearable motionaided devices and exoskeleton systems.

3.3.2. Prototype of water-activated rolling spherical robot

In addition to the excellent thermal performance of this material, its potential for pneumatic actuation is also of practical importance. Along this direction, we designed a water-triggered soft robot, which expands from a small volume into a sphere after water is applied and realizes movement including rolling and bouncing when an external force is added (Fig. 7(a)). The robot maintained a semi-spherical shape in its initial state. After injecting a specific amount of DI water into the cavity, the Al-NaOHeGaIn was triggered and the gas produced started to pump up the whole structure into a sphere. When the inflation process was finished, the spherical soft subject could easily be rolled, driven by airflow, or bounce after falling. Fig. 7(b) offers an intuitive view of the expansion process. The pumping process took only 30 s. As the process went on, the sphere expanded larger, making it easier to move under external stimulation. For the rolling test, a 5 W mini fan was adopted to generate a flow to imitate the breeze of a natural wind, and the sphere started rolling at an average speed of 1.1 cm·s-1 on a flat surface (Fig. 7(c)). Then the sphere was dropped from a height of 18 cm and reached a maximum height after bouncing of 9 cm, indicating 50% loss of its initial energy. However, the bouncing ability provides a possibility for the sphere to get over some obstacles in a complex field environment. The movability of the sphere is mainly determined by the degree of inflation, which is related to the diameter as well as the contact area of the bottom, reflected in the perimeter and friction. By controlling the water added, the device might be further regulated and realize more modes of motion. This device suggests a new path for the development of individual soft robotics without external devices.

《Fig. 7》

Fig. 7. Prototype of the water-activated rolling sphere. (a) Working mechanism of the water-triggered rolling sphere robot. (b) Real images of the sphere after being triggered. (c) Rolling of the sphere under airflow produced by a universal serial bus (USB) mini fan. (d) Bouncing behavior of the sphere when dropped from a height of 18 cm.

《4. Conclusion》

4. Conclusion

In summary, a water-triggered Al-NaOH-eGaIn material with excellent thermal and pneumatic performance has been developed. This material could rapidly respond to the addition of a tiny amount of water, resulting in a sharp temperature rise and a large amount of hydrogen production. Its thermal and pneumatic capabilities can be regulated through adjusting the volume of water added, which provides options for accurate control. In addition, the new material shows good reusability, as it can be retriggered at least five times and will degrade once it is immersed in an excess amount of water. This permits the recycling of eGaIn and harmless handling of the solution, indicating good environmental friendliness. Based on these characteristics of the AlNaOH-composited eGaIn, we fabricated a novel kind of fixation patch for medical application in the case of bone fracture or other injury consisting of BiInSn and Al-NaOH-eGaIn, with Al-NaOHcomposited eGaIn used as the inner layer. As a self-expansion material triggered by water, it can provide sufficient heat to melt the metal support layer on the outside of the patch and improve the fitness between the inner edge of the patch and the body curve. The fitting performance and loading ability of this smart patch have been tested, demonstrating its feasibility and reliability. In addition, a prototype of a water-triggered sphere robot was designed based on Al-NaOH-eGaIn, which realized rolling and bouncing behaviors under specific external conditions. Overall, the present material provides a new option for thermal and pneumatic actuators in a wide area, and could function as both thermal trigger for temperature-related phase transition materials and pneumatic trigger for the motion regulation of specific structures in soft robotics. It is expected that Al-NaOH-eGaIn holds big promise for future use in developing wearable motion-aided devices and exoskeleton systems, even soft robotics.

《Acknowledgements》

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by the Key Program of National Natural Science foundation of China (91748206) and Dean’s Research Funding and the Frontier Project of the Chinese Academy of Science.

《Compliance with ethics guidelines》

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Bo Yuan, Xuyang Sun, and Jing Liu declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

《Appendix A. Supplementary data》

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2019.08.020.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号