《1. Introduction》

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is inflicting an enormous toll on societies around the world. To deal with the pandemic, countries have adopted two types of isolation strategies for asymptomatic or mildly ill COVID-19 patients who do not require hospitalization: home isolation or community isolation. Home isolation has been adopted by many countries in the Americas and in Europe [1–4]. However, a major disadvantage of home isolation is that COVID-19 patients, even when asymptomatic or mildly ill, can still transmit the virus to their family or community members. Community isolation of COVID-19 patients in dedicated community isolation centers is an alternative isolation strategy that has been adopted by many East Asian countries, such as China, Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam [5–10]. A crucial advantage of community isolation is that it provides asymptomatic and mildly ill COVID-19 patients with a safe space to isolate outside their homes until they are no longer infectious [5,8,11,12].

For all isolation strategies, it is important to identify which COVID-19 patients are likely to progress to severe disease and require specialized hospital care [13,14]. The ability to identify such patients could guide decisions whether to isolate or hospitalize a patient and the design of routine monitoring and medical care of COVID-19 patients who are isolating [12,14,15].

Predicting the progression to severe disease is particularly important for COVID-19 because the disease often progresses rapidly [14–17]. Indeed, one major reason for the large differences in COVID-19 case–fatality ratios across countries may be the varying ability of national health systems to rapidly provide high-level care to patients [18–20]. While several studies have explored the risk factors of COVID-19 progression, most of these studies have focused on the transfer of COVID-19 patients within secondary or tertiary care hospitals from regular wards to intensive care units [19,21–29]. Our study focuses on progression from asymptomatic or mild to moderate symptoms—which can be treated at the community level—to more severe symptoms that require hospital care.

For this study, we used the clinical and health systems data collected from all patients in the largest of the community isolation centers—so-called Fangcang shelter hospitals—that were built in Wuhan, China during February and March 2020 [5]. The Fangcang shelter hospitals were an important component of the COVID-19 response in Wuhan, providing community isolation and care for COVID-19 patients who were either asymptomatic or suffered from mild to moderate symptoms. These community isolation centers were constructed within existing public infrastructures, such as stadiums and exhibition centers [5]. While the centers were developed and deployed for the first time during February and March 2020 in Wuhan, several other Asian communities have used this model of isolation and care for COVID-19 since then, as an alternative to home isolation [6,7,30].

The nurses and physicians working in the Fangcang shelter hospitals regularly monitored the disease progression of their patients and decided on a daily basis whether a patient needed to be referred to a higher level hospital because she/he developed more severe symptoms or signs indicating a deteriorating health status [5]. We used the clinical data that was routinely collected among all the patients in community isolation during the admission process to predict deterioration from asymptomatic, mild, or moderate COVID-19 to severe COVID-19. Our two competing outcomes in this survival analysis were deterioration (referral to a higher level hospital) and recovery (leading to discharge).

Our study provides important information for health policymakers and clinicians concerned with designing policies and systems for long-term COVID-19 control following the easing of lockdown policies in many countries [31–34]. In particular, our findings can inform the initial decision on whether to isolate and care for a patient who has newly tested positive for COVID-19 at home, in community facilities, or in higher level hospitals. Our findings can also inform the design of routine clinical monitoring and care for patients with no, mild, or moderate COVID-19 symptoms in home, community, or hospital isolation.

《2. Methods》

2. Methods

《2.1. Study population》

2.1. Study population

Our study population consisted of all patients with no, mild, or moderate COVID-19 symptoms who were admitted to the first and largest of the 16 Fangcang shelter hospitals that were constructed in Wuhan, China in February 2020 [5]. Our observation period lasted from 6 February 2020 (when the first patients were admitted to this community isolation center) to 9 March 2020 (when this center suspended operations because the number of new COVID19 cases had substantially declined in Wuhan). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were given to people who had come into close contact with COVID-19 patients or who presented with symptoms. The following official community isolation center admission criteria, which were adhered to across all of the 16 community isolation centers in Wuhan were then applied to determine the eligibility for admission [5]: ① a positive nucleic acid test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); ② either asymptomatic or mild signs or symptoms (mild clinical symptoms and imaging showing no signs of pneumonia) or moderate signs or symptoms (fever, respiratory tract symptoms, and imaging showing pneumonia); ③ ability to walk and live independently; ④ absence of severe chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, malignancy, structural lung disease, pulmonary heart disease, and immunosuppression; ⑤ no history of mental health conditions; ⑥ ≥ 5 and ≤ 65 years old (with the exception of patients who had family members in the same community isolation center); ⑦ a negative influenza test; and ⑧ blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) > 93% and respiratory rate < 30 breaths per minute. Patients were admitted to the Fangcang shelter hospital as a result of care seeking, contact tracing, or population screening for COVID-19. In Fig. 1, we show the distribution of the number of symptoms the patients in our sample suffered from upon admission to the Fangcang shelter hospital.

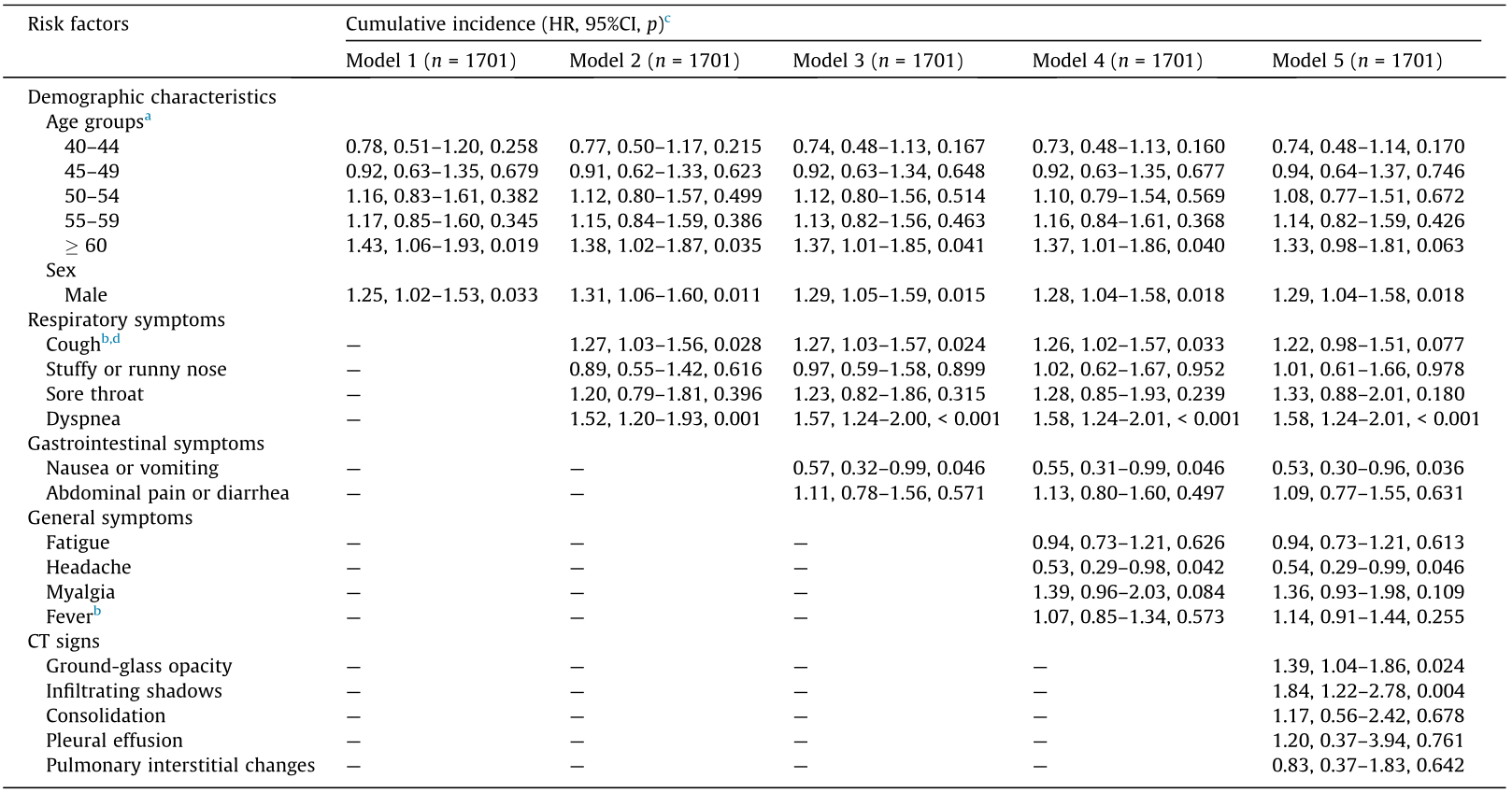

《Fig. 1》

Fig. 1. Distribution of symptom counts among patients upon admission to the Fangcang shelter hospital. 0 refers to patients who had no symptoms.

《2.2. Ethics》

2.2. Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Commission of the Union Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (KY-2020–01.01), and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Commission.

《2.3. Study location》

2.3. Study location

Located in the Jianghan district of Wuhan near the Yangtze River, the community isolation center that is the location of our study was the first and largest of the 16 Fangcang shelter hospitals in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province in China. It was built within the Wuhan International Conference and Exhibition Center. The distance from the community isolation center to the nearest higher level hospital designated for COVID-19 care was approximately 1 km.

《2.4. Outcomes》

2.4. Outcomes

Upon admission to the community isolation center, all COVID19 patients had no, mild, or moderate symptoms. Patients with deteriorating health status were quickly transferred from the community isolation center to higher level hospitals. Not a single COVID-19 patient died in the community isolation center during the observation period of this study. All patients in our study could thus develop only one of two mutually exclusive outcomes: deterioration (leading to referral) or recovery (leading to discharge).

2.4.1. Deterioration

If COVID-19 patients in the community isolation centers met any of the following clinical criteria, they were judged to have deteriorated and were rapidly referred to higher level hospitals designated for COVID-19 care [5,35]: ① respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths per minute; ② SpO2 ≤ 93%; ③ ratio of partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ≤ 300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 133 Pa); ④ lung imaging showing a greater than 50% progression of lesions within 24–48 hours; or ⑤ development of severe chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cancer, structural lung disease, pulmonary heart disease, or immunosuppression.

2.4.2. Recovery

If patientsmet any of the following clinical criteria, they were discharged from the community isolation centers because they were judged to have recovered: ① negative nucleic acid tests results for COVID-19 at two consecutive times with a sampling interval of at least one day;②normal body temperature formore than three days; ③ significant improvement of respiratory symptoms; or ④ lung imaging showing obvious absorption of inflammation.

《2.5. Predictors》

2.5. Predictors

We used three broad categories of predictors in our analysis. The choice of these predictor categories was based on data availability in the routine Fangcang shelter hospital database—all predictors used in this study were routinely collected from all patients upon admission to the community isolation center—as well as on usefulness for the routine monitoring of COVID-19 patients in a variety of settings. The first category comprises demographic characteristics (i.e., age and sex). The second category comprises clinical symptoms and consists of the following three subcategories: ① respiratory symptoms (cough or sputum, stuffy or runny nose, sore throat, and dyspnea); ② gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea or vomiting, and abdominal pain or diarrhea); and ③ general symptoms (fatigue, headache, myalgia, and fever). The third and final category comprises CT scan results (ground-glass opacity, infiltrating shadows, consolidation, pleural effusion, and pulmonary interstitial changes). Fever was defined as an axillary temperature of at least 37.5 °C. The CT signs were read and coded by radiologists.

《2.6. Statistical analysis》

2.6. Statistical analysis

We used a competing risk survival analysis to measure the predictors of progression from asymptomatic, mild, or moderate COVID-19 to severe COVID-19, because our outcomes data included the time to either of two mutually exclusive events: deterioration or recovery. For each patient with asymptomatic, mild, or moderate COVID-19, our observation period began upon admission to the community isolation center and ended when one of the following events occurred: ① the patient was transferred to a designated hospital for higher level clinical care because his or her clinical symptoms had deteriorated (outcome ‘‘deterioration”); ② the patient was discharged because he or she had recovered from COVID-19 (competing outcome ‘‘recovery”); or ③ neither ① nor ② had occurred before the community isolation center suspended operation (right-censored data). In the case of ③, the patients were transferred to higher level hospitals for continued isolation and care. In this case, the transfer took place because isolation and care in the community isolation center was no longer possible. We computed sub-distribution hazard ratios (HRs) in the competing risk survival analysis [36] to identify predictors of the absolute risk of deterioration during the time the patients stayed in community isolation [37–39].

We conducted both univariable and multivariable competing risk survival analyses. We adopted competing risk survival analyses because they are a valid, well-established procedure for estimating the cumulative recovery rate curve across a study period and are recommended by statisticians [40]. In our multivariable analyses, we sequentially added categories of potential predictors in nested regression models: demographic characteristics, symptoms, and CT signs. We assessed the proportional hazards assumption of the competing risk survival analysis using interaction terms between time and all other variables [41]. We used Stata version 15 to conduct the statistical analyses.

《3. Results》

3. Results

《3.1. Sample characteristics》

3.1. Sample characteristics

There were 1806 asymptomatic, mild, or moderate COVID-19 patients in community isolation who had a valid registration record in the database as of 9 March 2020 (the date on which the community isolation center was suspended). After excluding 53 patients with missing or invalid dates of admission (e.g., the date of admission was missing or was before the opening or after the closing of the Fangcang shelter hospital) or missing or invalid outcome data (e.g., the date of transfer or recovery was before the opening or after the closing of the Fangcang shelter hospital, or before the date of admission), we included 1753 inpatients in the final analysis. Out of these patients, 382 (21.8%) were transferred to designated higher level hospitals, 1270 (72.4%) were discharged, and 101 (5.8%) had right-censored outcomes data. The deterioration rate was slightly higher in our sample than in another study focusing on Fangcang shelter hospitals, in which 10% were transferred to designated hospitals due to deterioration [28].

The median time from admission to deterioration and transfer to designated hospitals was 16 days (interquartile range (IQR): 12–20), with a range of 0–30 days. The median time from admission to recovery was 14 days (IQR: 9–18), with a range of 0– 32 days. The median age of the 1753 patients was 50 years (IQR: 40–57), with a range of 15–73 years. Male patients accounted for 43% of the patients.

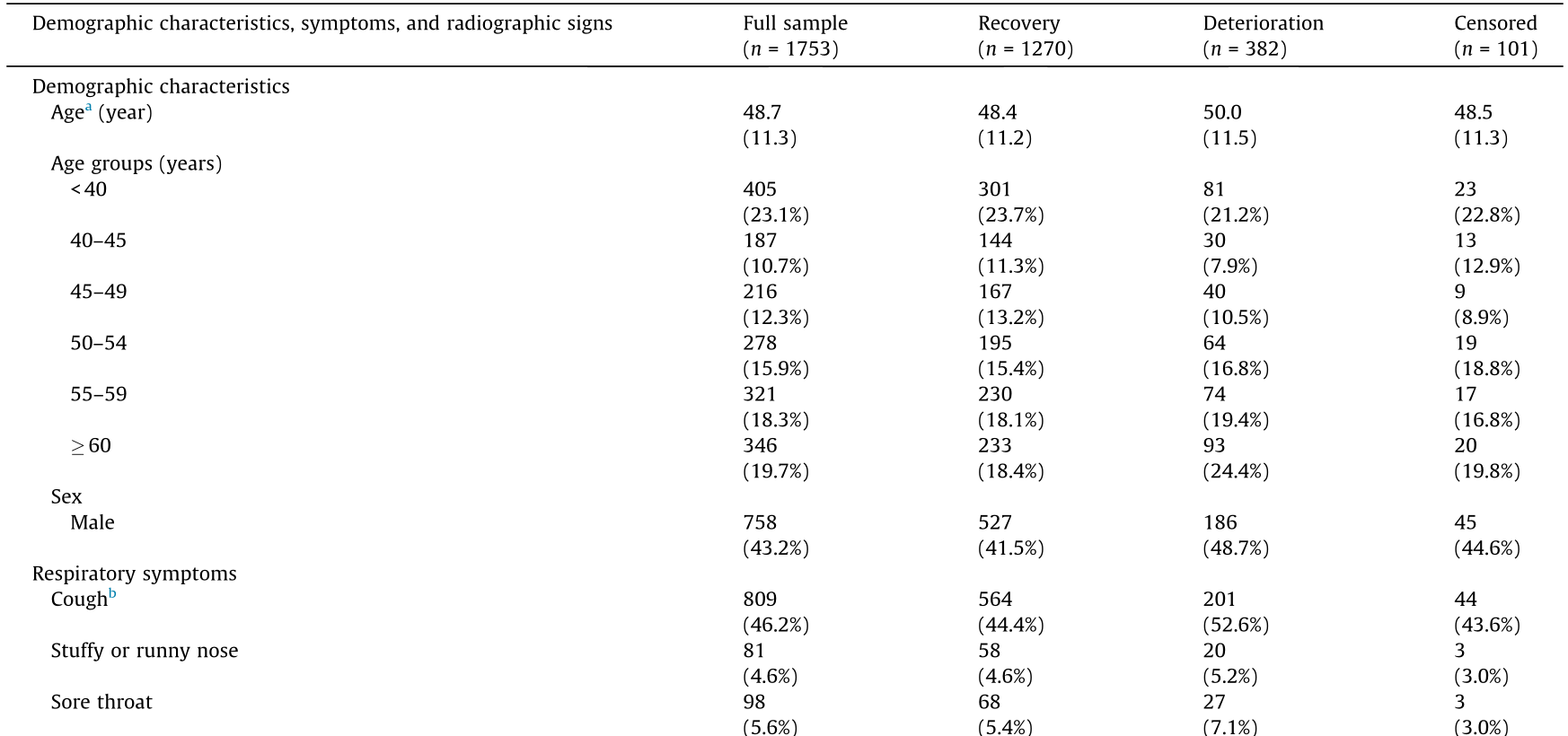

As shown in Fig. 1, most patients had one symptom (33.6%), while about one quarter (25.6%) of patients were asymptomatic. Patients who had four symptoms or less accounted for 93.4%. Patients with seven or more symptoms accounted for only 1.2% of all patients. The most common symptoms on admission were cough or fever, followed by fatigue and dyspnea. The most common CT sign was ground-glass opacity (Table 1).

《Table 1》

Table 1 Patients’ demographic characteristics, symptoms, and radiographic signs upon admission by outcome.

This table shows the demographic characteristics; respiratory, gastrointestinal, and general symptoms; and CT signs for all patients and for patients with deterioration, recovery, or right-censored outcome data.

a Values in the parentheses represent standard deviation.

b Cough includes cough with and without sputum production.

Fig. 2 presents the cumulative incidence curves for deterioration and recovery for all patients. The cumulative incidence for deterioration at days 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 was 1.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.0%–2.2%), 3.6% (95% CI 2.8%–4.5%), 9.8% (95% CI 8.5%–11.3%), 16.8% (95% CI 15.1%–18.7%), 21.2% (95% CI 19.3%– 23.2%), and 22.7% (95% CI 20.7%–24.7%), respectively. The cumulative incidence for recovery at days 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 was 5.3% (95% CI 4.3%–6.4%), 19.9% (95% CI 18.1%–21.9%), 41.8% (95% CI 39.5%–44.2%), 59.2% (95% CI 56.9%–61.5%), 71.1% (95% CI 68.9%– 73.2%), and 73.3% (95% CI 71.1%–75.4%), respectively.

《Fig. 2》

Fig. 2. Cumulative incidence of deterioration and recovery.

《3.2. Univariable competing risk regression》

3.2. Univariable competing risk regression

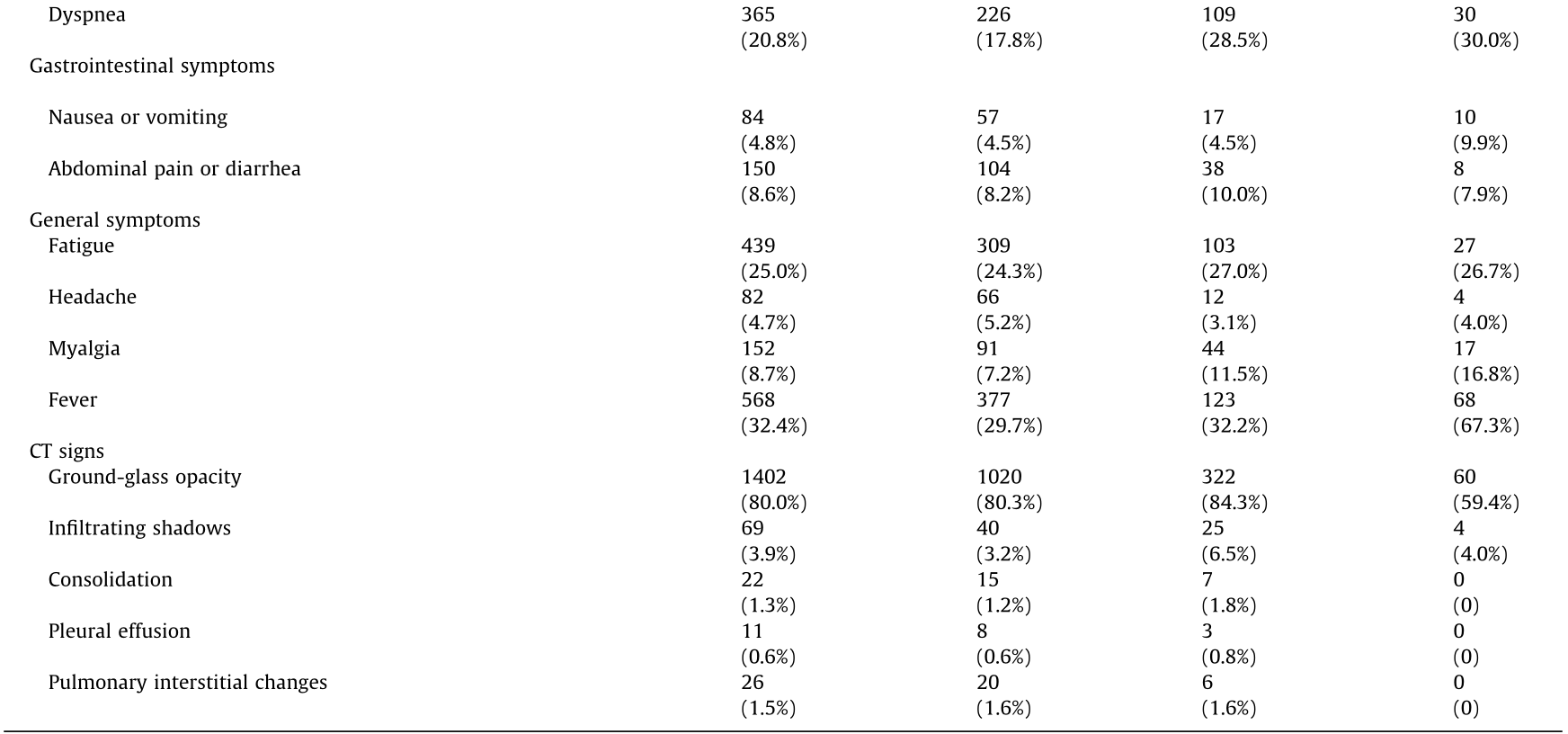

We show the cumulative incidence of progression to severe COVID-19 for the factors that are significant in multivariable competing risk survival analyses and are well-known risk factors of progression (Fig. 3(a)), CT scan signs (Fig. 3(b)), and common and unspecific disease symptoms (Fig. 3(c)). Fig. S1 in Appendix A provides the cumulative incidence curves for deterioration from the univariable regressions for other variables. In the univariable analysis, the HR of deterioration was higher in men and older patients (Fig. S2 in Appendix A). The symptoms at admission that significantly increased the cumulative incidence of deterioration were cough or sputum production (HR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.09–1.64, p = 0.004), dyspnea (HR = 1.61, 95% CI 1.29–2.02, p = 0.002), and infiltrating shadows (HR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.23–2.71, p < 0.001). Fig. S3 in Appendix A presents the cumulative incidence curves for recovery from univariable regressions.

《Fig. 3》

Fig. 3. Cumulative incidence of progression to severe COVID-19 for factors that are significant in multivariable competing risk survival analyses and are (a) well-known risk factors of progression, (b) CT scan signs, or (c) common and unspecific disease symptoms.

《3.3. Multivariable competing risk regression》

3.3. Multivariable competing risk regression

Table 2 shows the main results for the cumulative incidence of COVID-19 deterioration. In the multivariable model including all risk factors, deterioration was higher among men than women (HR = 1.29, 95% CI 1.04–1.58, p = 0.018), implying that male sex is associated with a 29% increase in the sub-distribution hazard of deterioration—that is, the instantaneous rate of occurrence of deterioration in subjects who have not yet experienced an event of deterioration [42]. Deterioration was lower among middleaged adults in comparison with younger adults and the elderly (Wald test of joint significance, p = 0.0943). Compared with patients aged below 40, the estimated risks of deterioration for the age group 40–44 and the age group 45–49 were lower (age group 40–44: HR = 0.74, 95% CI 0.48–1.14, p = 0.170; age group 45–49: HR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.64–1.37, p = 0.746), and the estimated risks of deterioration were higher for age groups older than 50 (age group 50–54: HR = 1.08, 95% CI 0.77–1.51, p = 0.672; age group 55– 59: HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.82–1.59, p = 0.426; and age group ≥ 60: HR = 1.33, 95% CI 0.98–1.81, p = 0.063).

《Table 2》

Table 2 Cumulative incidence of COVID-19 deterioration.

a Age group younger than 40 is the reference group.

b Evidence of violation of proportional hazards assumption in models 3 and 5 for cough, and in models 4 and 5 for fever. Estimates should be interpreted as the weighted average over the follow-up period.

c The regressions excluded 52 patients who were transferred immediately after admission. In all regressions, the total number of patients transferred, discharged, and censored were 372, 1228, and 101, respectively.

d Cough includes cough with and without sputum production.

The hazard of deterioration was higher among patients with dyspnea (HR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.24–2.01, p < 0.001) and lower among patients with nausea or vomiting (HR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.30–0.96, p = 0.036) than for patients without these symptoms at admission. Patients with CT signs of ground-glass opacity (HR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.04–1.86, p = 0.024) and infiltrating shadows (HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.22–2.78, p = 0.004) were significantly more likely to be transferred than to be discharged.

《4. Discussion》

4. Discussion

Our study provides answers to an important public health research question: Which factors predict progression to severe COVID-19 requiring hospitalization for intensive or complex care? Most previous studies elucidating the risk factors for COVID-19 progression have used data from COVID-19 patients that were already hospitalized with relatively severe symptoms [19,21–29]. However, most COVID-19 patients never require hospitalization and can be isolated and cared for at home or in community facilities. We used data from COVID-19 patients in community isolation in Wuhan, China, to determine the factors predicting COVID-19 progression. Most COVID-19 patients in our sample had mild to moderate symptoms; about one quarter of patients were asymptomatic. One in five patients in community isolation eventually needed the intensive or complex treatments that were only available in higher level hospitals designated for COVID-19 care. Another important advantage of this study is that we tried to include a list of potential risk factors based on low-cost diagnostic information, such as demographic and social characteristics, as well as easily identifiable symptoms. In low-income countries or settings where expensive CT scans are difficult to perform, this low-cost information is crucial for designing triage and isolation strategies and minimizing the economic harm of COVID-19 [43,44].

The most common clinical symptoms among the COVID-19 patients that were monitored and cared for in the community center in Wuhan were cough and fever, followed by fatigue and dyspnea. The standard protocol for community isolation in Wuhan included CT scans to rule out signs of severe disease. The most common CT sign among patients in the community center was ground-glass opacity.

Male sex, dyspnea, and ground-glass opacities and infiltrating shadows in CT scans were important predictors of progression to severe COVID-19 rather than recovery. These findings demonstrate that several important risk factors of progression to severe COVID19 are similar among patients in community isolation and among patients already needing hospitalization [45–50]. For example, increasing evidence shows that COVID-19 produces more severe symptoms and higher mortality among men than women, which is likely due to sex differences in immune responses during the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection [51]. Knowledge gained among hospitalized patients may thus be at least partially generalizable to milder cases of COVID-19 in patients in community or home isolation. Our findings also indicate that two easily identifiable risk factors—namely, male sex and dyspnea—should guide public health and clinical decisions regarding the intensity of monitoring and referral to designated hospitals. The strong associations of two specific CT symptoms with a deteriorating course of COVID-19 further suggest that countries where mass CT scanning is technologically feasible and affordable should consider adding CT scans to the routine clinical work-up of COVID-19 patients whose symptoms do not already indicate a need for hospitalization. Such decisions should be supported by future cost-effectiveness analyses of CT scans for screening COVID-19 patients to decide whether they should be hospitalized or not. It is possible that CT scans will indeed be cost-effective for the routine screening of COVID-19 patients, because most patients in most pandemic situations cannot be hospitalized, while patients that experience a deteriorating course of the disease often do so rapidly and with a relatively high risk of mortality if they do not quickly receive higher level care [18–20]. CT scan results may substantially and cost-effectively improve the outcomes of triage decisions that separate patients into those requiring immediate hospitalization and those that can be isolated in community centers or at home.

Headaches and nausea or vomiting were significant factors associated with a reduced risk of severe COVID-19 among our sample of patients in community isolation. The reason for these findings is unlikely to be biological. Headaches and nausea or vomiting are not specific symptoms of COVID-19, but occur in people suffering from a large number of other diseases and conditions. For example, previous research has found that, during pandemic, stress, mask wearing, social isolation, and taking medicines can all trigger headaches, of which nausea is an accompanying symptom [52]. The likely explanation for these "protective" associations is thus that increased stress induced by people’s fear of COVID-19 or coincidental diseases other than COVID-19 led patients to visit COVID-19 testing facilities or general outpatient healthcare, where they received COVID-19 tests [53]. These tests, in turn, led to COVID-19 diagnosis and subsequent isolation in community centers. Because the unspecific symptoms that brought these patients to the community center were likely caused by mostly harmless diseases (such as migraine or viral gastroenteritis)—rather than by COVID-19—these patients were less likely to progress to severe COVID-19 than other patients in the center, who were more likely to have presented with symptoms already indicating a degree of COVID-19 progression, which, in turn, increases the risk of further deterioration. Another study in China also reported on the ‘‘protective” association of nausea on disease progression among COVID19 patients [54]. This finding has implications for the routine monitoring of patients in community and home isolation. Patients with unspecific symptoms occuring in many harmless diseases may face a similar overall risk of COVID-19 deterioration as patients with asymptomatic COVID-19. Both groups are likely to be relatively safe in home or community isolation and have lower priority for monitoring and triage to higher level care than patients suffering from symptoms specific to COVID-19.

Our finding that common unspecific symptoms can induce selection effects in triage and prioritization systems has public health relevance far beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research should test alternative approaches to guard against inefficiencies in triage and prioritization that can occur because patients suffering harmless comorbidities are more likely to seek health care, which then leads to diagnostic detection and health system prioritization for an unrelated disease. Such knowledge could be actively incorporated into triage algorithms, for example, by adding further screening tests with prognostic value for those patients who are considered for prioritization for one potentially dangerous disease, but suffer from common unspecific symptoms indicative of many other harmless diseases.

Our study has a few important limitations. First, the public health guidelines for community isolation in China stipulated that COVID-19 patients with important comorbidities [55], including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and mental health conditions, should be hospitalized rather than receive care in a community center [5]. We were thus unable to investigate comorbidities as risk factors for COVID-19 deterioration. Second, we did not have access to other risk factors that could predict disease progression. For example, smoking was associated with COVID-19 disease progression in hospitals [56]. In China, about half of adult men smoke, which is much higher than the prevalence of smoking among women [57,58]. It is possible that smoking may partially explain the elevated risk in men in this study. Third, we did not have access to laboratory tests and other biomarkers that could be important predictors of COVID-19 deterioration. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that other factors could be important for early COVID-19 triage decisions. These limitations, however, do not reduce the usefulness of the findings on which factors predict COVID-19 deterioration and which do not. Our findings are broadly relevant for all contexts, including resource-poor communities, because they relate to symptoms and signs—that is, factors whose values can be measured at low cost and with simple and robust technologies. These findings are also relevant for resource-rich health systems in which CT capacity is widely available and CT use is generally affordable.

In sum, our study finds that male sex, old age, dyspnea, and ground-glass opacity and infiltrating shadows in CT scans were strong predictors of severe COVID-19 deterioration among patients in community isolation. We also find that common and unspecific symptoms—namely, headaches and nausea or vomiting—have likely induced a selection of COVID-19 patients for community isolation who are relatively unlikely to experience severe disease deterioration. Future public health and clinical guidelines should build on this evidence to design better screening and triage systems, as well as monitoring and care pathways, to ensure effective, safe, and efficient community isolation.

《Acknowledgments》

Acknowledgments

We thank all health workers working in the Fangcang shelter hospitals. Simiao Chen was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Germany and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Project INV-006261). Pascal Geldsetzer was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR003143). Till Bärnighausen was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the Alexander von Humboldt Professor award, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the European Union’s Research and Innovation Programme Horizon 2020, and the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP). Simiao Chen, Till Bärnighausen, Chen Wang, Juntao Yang, Zhuoran Wang, and Peixin Wu were also supported by the Sino-German Center for Research Promotion (Project C-0048), which is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC).

《Compliance with ethics guidelines》

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Simiao Chen, Hui Sun, Mei Heng, Xunliang Tong, Pascal Geldsetzer, Zhuoran Wang, Peixin Wu, Juntao Yang, Yu Hu, Chen Wang, and Till Bärnighausen declare that they have no conflict of interest or financial conflicts to disclose.

《Appendix A. Supplementary data》

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.07.021.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号