《1.Introduction》

1.Introduction

Metro Line 1 of the Naples underground metro system began from a first draft in 1976, and has been developed through subsequent insights and novel strategies to become the main instrument of urban and social transformation for the city of Naples. The major stations built at the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s, including the Viennese railway stations designed by Otto Wagner, express a committed intention to create a form of architecture to enhance the technical undertaking of transport infrastructure. However, unlike these, most of the railway station projects in other cities have been exclusively aimed at enhancing technical and engineering concepts. The infrastructure of such stations is only created to allow accessibility to specific areas, and the station itself is simply a place through which this infrastructure could be accessed. For a long time, and in many cases still today, this lack of quality has turned underground rapid transit stations and railway stations into urban spaces of degradation, even though they are located in central areas of the city: Such spaces cannot provide urban renewal to the city, nor can they be used for citypromoting activities

MN Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A. (hereafter referred as MN) is the general contractor of the city of Naples for the design and construction of Metro Line 1. Since 1990, in agreement with the municipal administration, MN has felt the need to provide a more competitive alternative to private transport, including the necessary revitalization of the underground and aboveground spaces, in order to increase public use of the underground rapid transit system and raise public perception of the efficiency and safety of the system.

《2.Art》

2.Art

The first experience with this revitalization was realized with the construction of the Vanvitelli–Dante subway segment. This undertaking consisted of revitalizing the underground spaces, which are crossed daily by hundreds of thousands of citizens, with contemporary artworks. This experiment, which has progressively seen the involvement of almost 200 artists, was the first of its kind in Italy, and may well be the first in the rest of the world as well.

A huge number of artworks were installed under the name of ‘‘public art.” In the words of Professor Achille Bonito Oliva, a consultant of MN and the curator of this experience, ‘‘public art is not simple furnishings or decorations to the architectural envelope; rather, it is a structure that interacts with the existing structure of the architectural shell and randomly draws the happy gaze of the public, who pass through these spaces with attention and sometimes with carelessness.”

Therefore, the revitalized Salvator Rosa Station (Fig. 1), Cilea Station (Fig. 2), Materdei Station (Fig. 3), Museo Station (Fig. 4), and Dante Station (Fig. 5) now represent a sort of ‘‘obligatory museum” and have earned the title of ‘‘Stations of Art” in the collective imagination.

《Fig. 1》

Fig.1.Salvator Rosa Station.(Photo credit:Luca Pioltelli)

《Fig. 2》

Fig.2.Cilea Station exhibits work by the artist Marisa Albanese.(Photo credit:Peppe Avallone)

《Fig. 3》

Fig.3.Materdei Station showcases work by the artist Sol Lewitt.(Photo credit:Peppe Avallone)

《Fig. 4》

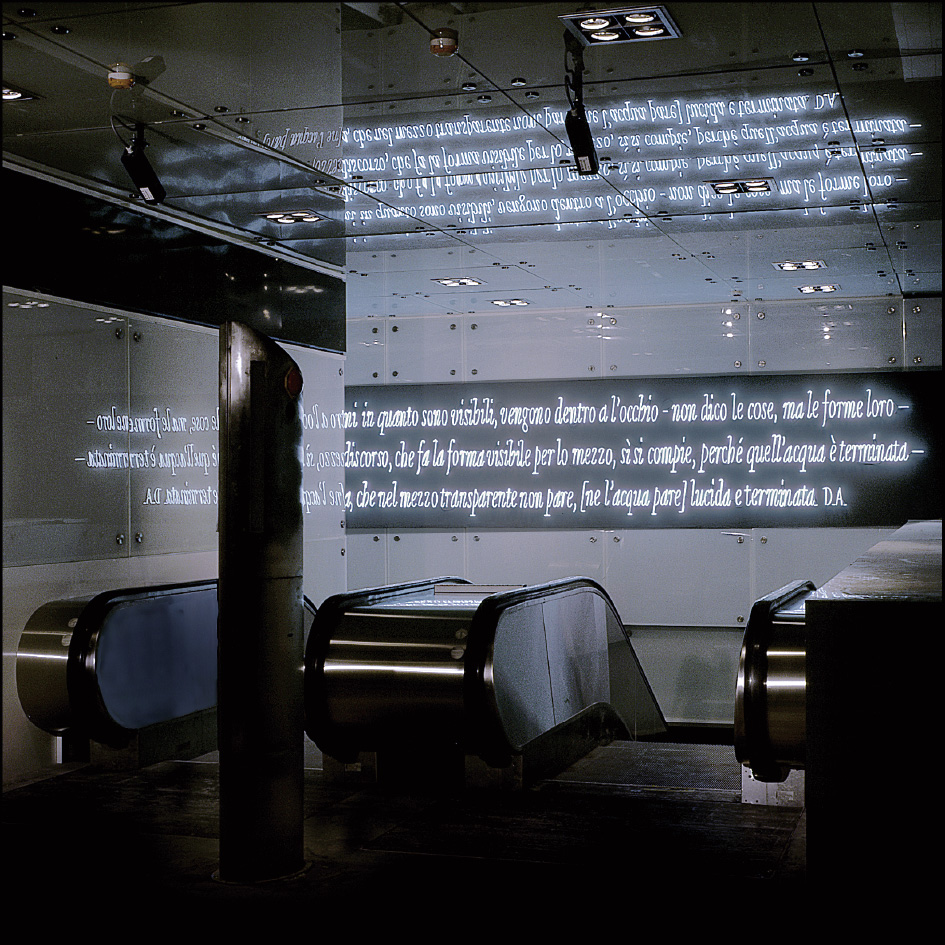

Fig.4.Museo Station displays work by the artist Mimmo Iodice.(Photo credit:Peppe Avallone)

《Fig. 5》

Fig.5.Dante Station exhibits work by the artist Joseph Kosuth.(Photo credit:Peppe Avallone)

This initial experiment has already improved the common landscape, if a ‘‘landscape” is understood not only as an open space, but also as any closed space, even an underground space, that is enjoyed or participated in by those who cross it at a particular moment.

After commissioning the Stations of Art and realizing the renewal of the downtown stations, it was necessary to manage the huge quantity of archeological findings and relate these to the history of the city of Naples, which encompasses the entire Mediterranean culture from the age of Magna Graecia to the present day.

《3.Archeology and architecture》

3.Archeology and architecture

By means of stratigraphic excavations, conducted in agreement with the archeological authority, all the historical periods through which Naples has passed, without solution of continuity, have been ‘‘rediscovered,” and exceptional descriptions have been written, allowing historians to rewrite important pages in the local urban evolution.

The scientific results of these excavations, which were conducted under the supervision of the Sovrintendenza Archeologica, are outside of the scope of this article, and contain so many discoveries that they would require years to be fully described. Notable discoveries include:

• A Roman shrine to the Isolympic Games,found in Piazza Nicola Amore (Fig.6);

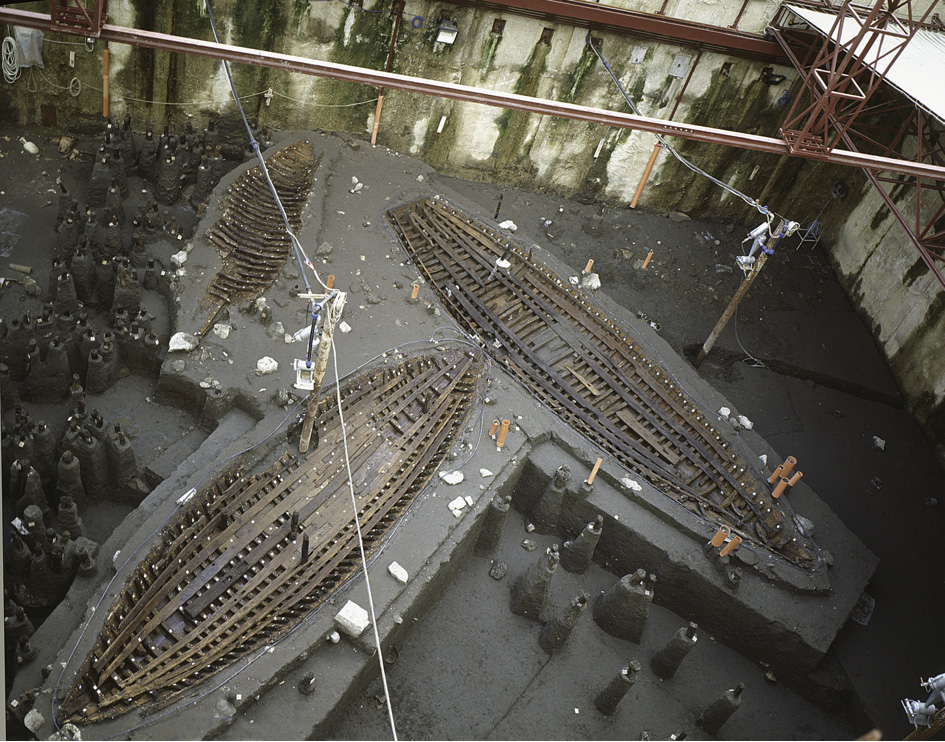

• A port built in the classical age,discovered in Piazza Municipio( Fig.7); and

• Parts of the Angioino District (XIII century) around Castel Nuovo (Fig.8).

《Fig. 6》

Fig.6.Duomo Station exhibits a Roman shrine to the Isolympic Games,a competition that followed the same regulations as the original Olympic Games of Ancient Greece.(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

《Fig. 7》

Fig.7.Municipio Station displays a Roman harbor.(Source:Archives of Metropoli-tana di Napoli S.p.A.)

《Fig. 8》

Fig.8.Municipio Station displays an excavation of the Angioino District(XIII century).(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

In light of these discoveries, it was considered to be a primary aim to proceed with the integration, as far as possible, of archeological findings into the design of the stations. This was done by collaborating with architects with proven international experience, who could bring quality design to the implementation of the infrastructural architecture in combination with archeology and contemporary art, thus giving life to the three ‘‘As” of the Naples metro system.

Through this concept, the Naples metro system represents an opportunity for urban redevelopment; this project sets in motion a process of true transformation for the city.

The Municipio Station, designed by the architects Alvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura, will be the best entrance to the city of Naples to welcome tourists coming from ocean routes. The architectural design of this station is based on structural works that were already realized under transportation criteria; for that matter, the Metro Line 1 track did not correlate well with the urban axes on the surface. Therefore, this project has had to articulate the different imprints of the Piazza Municipio and the rectangular well of the station by using a mezzanine plan to rearrange the pedestrian fluxes from the train level to the ground level. One of the goals of the project was to merge two different axis: the surface one and the Metro Line 1 track. The rotation has been realized at the mezzanine level.

In the realization of the Naples metro system, the excavation is itself a work in progress that follows the rhythm of the processing of archeological research. At the mezzanine level, the Municipio Station aligns with the discovery of the walls of Castel Nuovo from the Middle Ages, and with other constructions from ancient times up to the Roman Era; these discoveries are now part of the public space, and were considered to be the primary element of the project design and of the structural construction of the station. For example, the stone walls of the ancient castle are used as a support structure for the concrete cover of the mezzanine level. These walls are also fundamental in the final configuration and design of the interior spaces of the station. The excavations, deviations of the infrastructural network, access requirements, and other constraints have thus defined a new urban design.

The construction of the Naples metro system constitutes the foundation of a deep urban transformation. This transformation includes the definition of a continuous space between the Municipio Station and the Maritime Station (Figs. 9 and 10).

《Fig. 9》

Fig.9.The new Municipio Square with the historical layers.(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

《Fig. 10》

Fig.10.The Piazza Municipio at night.(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

This east-west urban axis was accentuated by using the same material for the floor of the whole square, and by implanting two continuous alignments of trees (Quercus ilex) that extend from Palazzo San Giacomo down to the Maritime Station. Over the course of history, as confirmed by abundant iconography, this visual of a continuous space with the hill of Castel Sant’Elmo as the background is a fundamental frame of the geography of Naples, and has been kept as a priority objective of this project.

《4.Urban renewal》

4.Urban renewal

Each urban design has its own history and its own raison d’être. In Naples, the most emblematic of these is, without a doubt, the renewal of Piazza Garibaldi. When dealing with the topic of Piazza Garibaldi in 2005, in consultation with the architect Dominique Perrault and the municipal administration, the need to establish a different urban environment at this location was immediately emphasized. In this case, the area of intervention was unique, encompassing an entire urban area that was complex in terms of both size and logistics.

Piazza Garibaldi is significantly important in comparison with all other Neapolitan squares, and is logistically linked to its position on a virtual boundary between the historic part of Naples and more recent development; thus, the piazza acts as an interchange hub of transport between the city and suburban areas. The revitalization of Piazza Garibaldi began with the goal of working out a proposal that was capable of initiating a complete renewal of the entire urban area, by extending as far as possible the borders of action and reaction for this urban renewal project.

Given the current administration, which promotes the progressive limitation of private transportation and facilitates the growth of public transportation, it may be said that the future of this district will depend on the process of strengthening and rationalizing transportation both private and public, as determined by the following concepts:

(1) Optimization of the public transport network (train, metro, bus, and taxi) by improving the usability of these services by the public, including promotion of bicycle use.

(2) Improvement of the road network on the surface,with the launch of a new platform that is able to manage traffic information.

(3) Restructuring of the existing stations and the provision of a network of pedestrian links on various levels to ensure good access to the new metro stations, and careful relocation of underground and aboveground spaces where necessary.

Urban redevelopment on this scale must necessarily be accompanied by a very strong political will, and requires a special architectural quality. Piazza Garibaldi already represents an urban space that is full of vivacity and movement, and reflects the needs and character of the Neapolitan people. This project aims to preserve and enhance this identity, which is inherent to the place, while simultaneously attempting to solve more problematic aspects related to the congestion of vehicular traffic and the extreme fragmentation of the public use of these spaces.

The existing station is a concrete monument; the design of the extensive coverage of the southern part of the piazza develops as a continuation of the old building roof, in an evolution and transformation of the theme abri, meaning shelter and protection. The new structure differs totally in terms of materials and line from the existing superstructure (the elegant work of Pier Luigi Nervi); however, it preserves the dimensional connotation, which expresses a very special relationship with the context, the existing structure and the new structure have the same height.

The square is then divided by its two distinct functions (Fig. 11):

《Fig. 11》

Fig.11.A computer-aided design(CAD)image of the new Garibaldi Square.(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

• The north part of the square contains a space consisting of gardens, and a belowground square that provides access to Metro Lines 1 and 2, highlighted by the presence of space for displays and/or performances by street artists.

• The south part is a protected space, and is shielded from the sun by a large permanent canopy structure containing a subterranean walkway. Here, pedestrian traffic mixes with users of varying origins and destinations (Naples Central Railway Station, Circumvesuviana Railway Station, and Metro Line 2). This walkway, or commercial gallery, is intended to be an entry to the ‘‘underworld” of the metro system; it is both parallel to and firmly integrated with the aboveground city (Fig. 12). The Piazza Garibaldi project is thus an emblem of how a great infrastructure of collective transport can induce a complete urban transformation.

《Fig. 12》

Fig.12.The commercial gallery at Garibaldi Station.(Source:Archives of Metropolitana di Napoli S.p.A.)

《5.The most beautiful station in Europe》

5.The most beautiful station in Europe

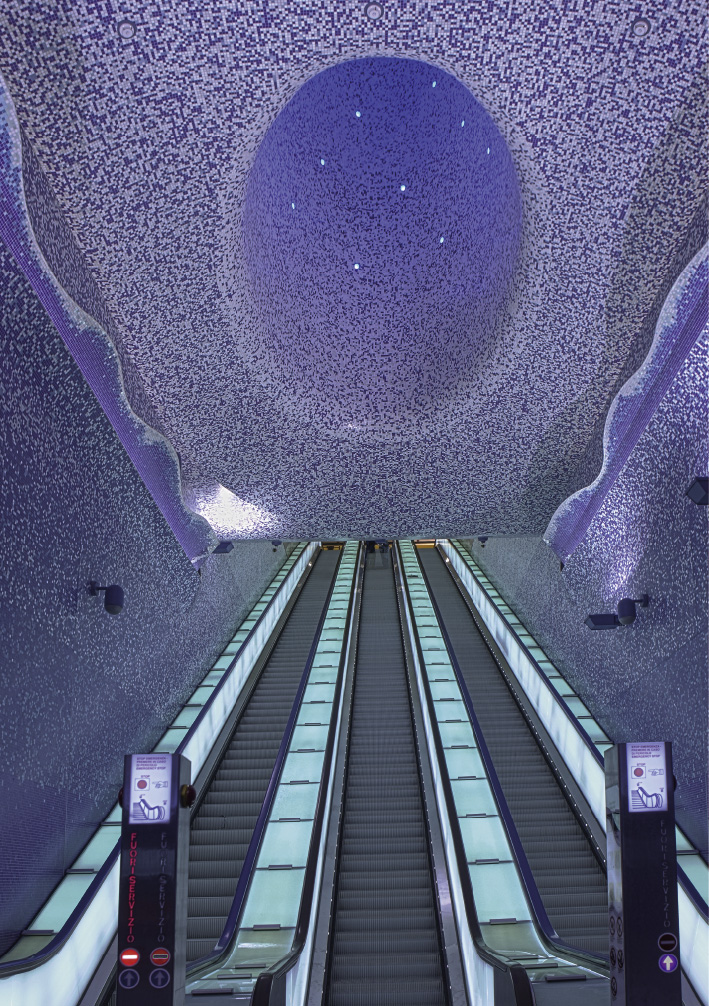

Toledo Station was designed by the architect Oscar Tusquets Blanca of Barcelona, and is a masterpiece. In fact, based on a survey that was conducted by the prestigious English newspaper The Daily Telegraph in major European cities, this station was designated the most beautiful of all the underground stations of Europe. The Toledo Station project represents a synthesis of the design strategy used in the Naples metro system.

This station is located between two contradictory sides of Naples: on the one hand, an ancient and problematic part of Naples, the Spanish Quarter, which began around 1500 as a military camp of the Spanish soldiers occupying Naples; and, on the other hand, the Via Toledo, a commercial and institutional headquarters that still bears the name of Viceroy Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, who first built it.

The general concept of the design is based on the concept of the ‘‘sea level” that horizontally divides the station interior. Above this level, the station is visually designed as the inside of an excavation, showing the Aragonian wall that was found during construction. Below the aquifer level, the user has the impression of diving underwater, due to the colors and materials selected by the architect (Fig. 13).

《Fig. 13》

Fig.13.The light cone of the Toledo Station.(Photo credit:Peppe Avallone)

All the floors are crossed by a large cone of natural light, as a periscope is open from the road surface above to a depth of 30 m below, allowing people on the surface to admire the immersed passage of subway users, and creating a ‘‘real” underwater architecture. Passengers on their way to and from trains will be drawn into the cone of light, which is coated in a mosaic colored in various shades of blue; the mosaic is partly lit by natural light coming from the surface and partly by the light artwork of Bob Wilson, which consists of LED lights in various intensities of blue and white.

The station is completed with the other artwork of Bob Wilson, which consists of backlit panels showing sea waves in slow motion, and with the artworks of William Kentridge (Fig. 14). In addition to two mosaics inside, William Kentridge has produced a wonderful equestrian sculpture for the new avenue that is integrated into the surface design by the architect, Oscar Tusquets Blanca (Fig. 15)

《Fig. 14》

Fig. 14. A mosaic by William Kentridge at Toledo Station. (Photo credit: Daniele Puglia)

《Fig. 15》

Fig.15.An equestrian sculpture by William Kentridge in Toledo Square.

The opening of the second exit of Toledo Station, in Piazza Montecalvario, completes a ‘‘network” project depicting the Spanish Quarter along a mechanized corridor; the traveler will encounter a myriad of characters photographed by Oliviero Toscani. Along the ascent into Piazza Montecalvario, passersby will appreciate the works of other artists, up to the mezzanine floor that will host a large mosaic by Francesco Clemente. The surface design of the piazza is articulated on multiple levels; designed by Oscar Tusquets Blanca, it blends perfectly with the urban context.

Art, archeology, and architecture thus characterize the design of the metro system in the historical center of Naples. The next step, with the agreement of the municipal administration, will be a line extension to Capodichino, Naples International Airport. Subsequent urban interventions will then be guided by the goal of triggering a real urban development in the suburban areas at the periphery of the north-east part of the city.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号