One day in late 2022 or early 2023, a customer somewhere in the United States will make history by purchasing the first pair of hearing aids sold over the counter (OTC). For more than 40 years, these devices have been available in the United States and many other countries mainly through audiologists or other hearing professionals. But updated regulations scheduled for enactment later this year by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the US agency that oversees drugs and medical devices, will allow retailers to sell hearing aids directly to consumers [1].

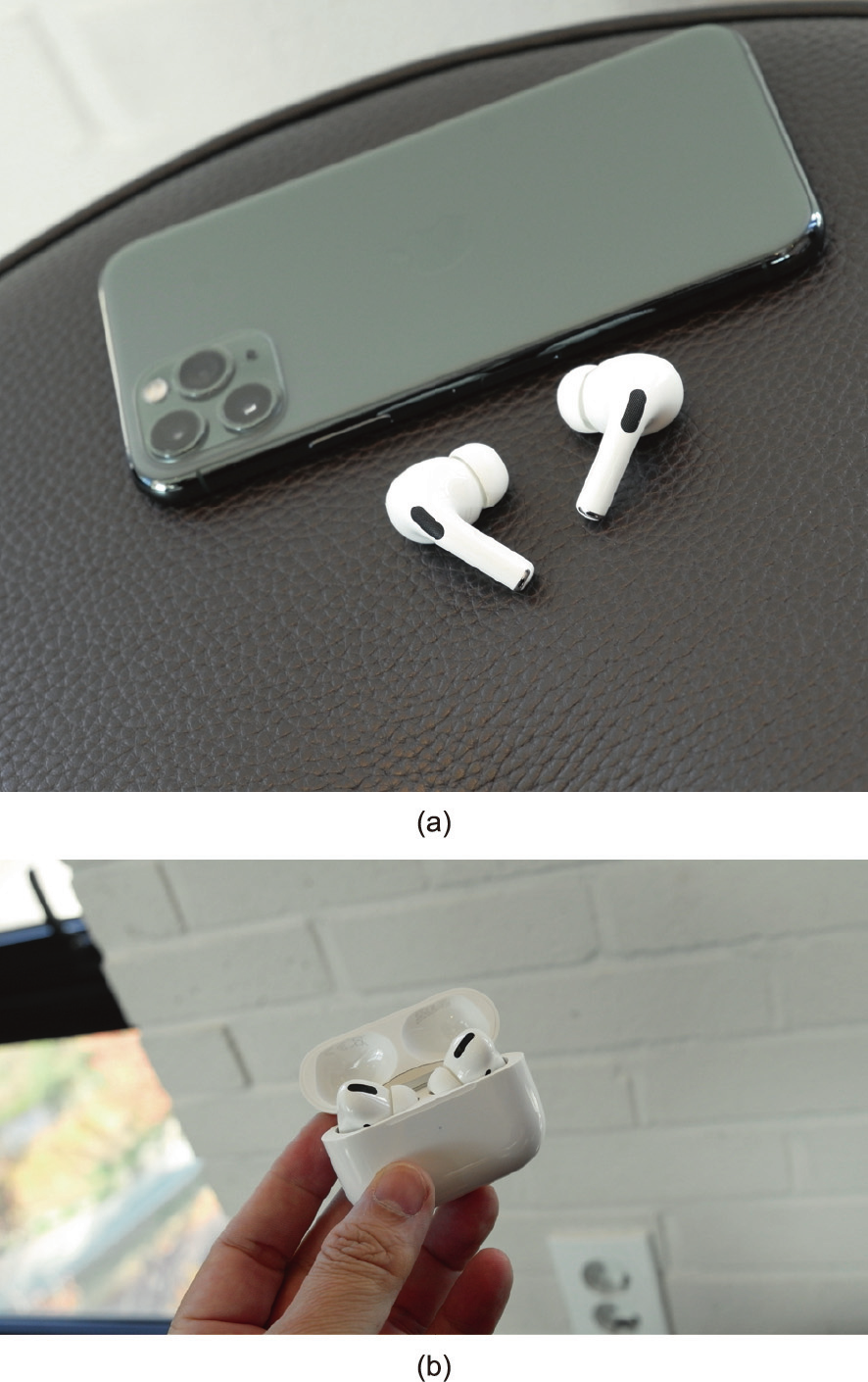

This change will lead to ‘‘a huge disruption in the delivery of hearing aids,” said Elaine Mormer, an audiologist and professor of communication science and disorders at the University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA. The devices will be available to millions more people in the United States who currently cannot afford them or have no way to obtain them [2]. More companies will enter the hearing aid market, experts predict, spurring rapid innovation that could make the devices not only cheaper, but also more capable, easier to use, and more stylish [3]. The regulations may also help customers benefit from hearing-improving technologies found in other consumer products. Apple, for example, hopes to market its top-of-the-line ear buds as hearing aids (Fig. 1) [4,5].

《Fig. 1》

Fig. 1. (a) Although they cannot yet be marketed as hearing aids, Apple’s AirPods Pro ear buds incorporate sophisticated sound processing that can be controlled with a cell phone app. And, according to the results of one study, they enhance speech intelligibility by about as much as hearing aids with directional microphones [5]. (b) Unlike many hearing aids still sold today, the much less expensive ear buds— and almost all bluetooth-paired cell phone accessories—are rechargeable. Credit: HS You (CC BY-NC 2.0).

And if this do-it-yourself approach to hearing care proves successful, other countries could follow suit, said Nicholas Reed, assistant professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, MD, USA. ‘‘The US is the experimental case.”

Hearing loss is prevalent, with about 40 million people in the United States suffering from reduced sound sensitivity in both ears [6]. Impairment becomes more common with age, affecting 25% of people between 65 and 74 and 50% of people 75 and over [7]. And the problem is global. A 2021 report from the World Health Organization estimated that 430 million people suffer from ‘‘disabling hearing loss” and projected that number would climb to almost 700 million by 2050 [8]. People with hearing loss are at greater risk for a variety of health problems, researchers have found, including depression, cognitive decline, and heart disease [9]. ‘‘It is arguably the single largest risk factor for dementia,” said Frank Lin, professor of otolaryngology and director of the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health at the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health.

Hearing aids do not correct the underlying defects that cause hearing loss. They amplify sound. Today’s devices rely on a variety of technologies and sound processing strategies to improve the quality of their output and tailor it to the wearer’s specific needs. They often feature an omnidirectional microphone that captures sound from all around the user as well as a directional microphone that typically points forward and can help separate speech from noise, one of the biggest challenges for wearers [10]. Noise reduction algorithms also help refine the output, and some hearing aids can now perform ‘‘split processing,” which involves breaking down and analyzing the input from forward and rear microphones separately to accentuate certain sounds and suppress background noise [11]. Some devices also employ artificial intelligence algorithms that can learn a wearer’s hearing habits and preferences and adjust the output accordingly [12]. And many hearing aids pair with cell phones or other electronics through bluetooth, allowing users to stream music, participate in video calls, listen to TV audio, and fine-tune sound levels [13,14].

The catch is that under the old FDA regulations enacted in 1977, obtaining hearing aids is complicated and costly [1]. A patient who suspected their hearing was declining would likely first see a doctor, who would check for a medical explanation [15]. If none were found, the next step would be a hearing test from an audiologist or a technician with less, but more specific, training, such as a hearing aid dispenser. This person then sells the patient hearing aids customized to fit their ears and to amplify the frequencies that they need or want to hear. Users often require several follow-up visits for adjustments to ensure the devices are performing properly.

Not only are hearing aids expensive in the United States, from 1000 to 14 000 USD per pair [1], but patients also must often bear the full cost themselves. Medicare, the US government medical insurance program for people aged 65 and older, does not currently cover hearing tests or hearing aids, and the same applies for most private insurance plans [13]. Not surprisingly, only about 16% of people in the United States between the ages of 20 and 69 who need the devices actually wear them [7].

‘‘Easier and less expensive access to hearing aids would have huge public health benefits,” said James Naples, assistant professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA, USA. The FDA is taking the right approach by targeting accessibility and cost, the two biggest obstacles to increased hearing aid use, said Mormer. People will be able to buy devices to improve their hearing not just from audiologists and hearing aid dispensers, but also from pharmacies, electronics stores, and other retailers. And by expanding the hearing aid market, now dominated by five large companies, the new regulations should boost competition and drive prices down, said Lin, who predicted some models could cost as little as 100 USD within a few years.

Increased competition could also spark further innovation, like the rechargeable hearing aids powered by lithium-ion batteries that finally reached the market in recent years. They are an upgrade from previous models—for decades, many elderly users with poor eyesight and arthritic fingers have had to fumble with tiny, expensive batteries that last no more than a few days.

One important benefit of the FDA’s new rules, said Reed, is that they will help consumers sort through a confusing range of hearing-improvement options. For example, some consumer products boast powerful sound processing capabilities but currently do not qualify as hearing aids. One category of these devices includes personal sound amplification products (PSAPs), which allow people to hear better in noisy public places or other settings [16]. Although PSAPs were designed to boost the sound sensitivity of people with normal hearing, some consumers use them as hearing aids because of their low cost—as little as 100 USD [17]. Indeed, a 2017 study by Reed, Lin, and colleagues suggested these people were not losing that much, with some PSAPS that cost around 350 USD improving speech understanding by almost as much as much more expensive hearing aids [18].

A second category contains the so-called hearables, wireless devices worn in the ear that can perform functions as diverse as playing music and tracking blood pressure [19]. Apple’s latest AirPods Pro ear buds, which cost around 200 USD, are an example. Such devices employ algorithms to shape the sounds the user hears. Some can even give the user hearing tests (like an audiologist’s examination) and then customize their output, increasing the volume of the frequencies that person has the most trouble discerning [20]. An additional feature of the AirPod Pros makes it easier to carry on conversations by amplifying the speech of anyone who is directly in front of the wearer [21].

Some manufacturers, such as Eargo, based in San Jose, CA, USA, already sell hearing aids directly to users over the Internet (Fig. 2), which is legal if the companies meet FDA labeling and consumer information requirements [22]. But to qualify for OTC sale under the new FDA regulations, devices will have to meet a variety of design and performance specifications, including maximum volume, amount of self-generated noise, and distance extended into the ear [23]. The maximum volume at any frequency is 115 dB in most cases, and the regulations also require the devices to span the frequency range of 250 Hz to 5 kHz which includes most speech. Consumers who choose OTC hearing aids will know what they are getting, Reed said. ‘‘This means you would have a device that says, ‘FDA approved hearing aid.’ That is appealing.”

《Fig. 2》

Fig. 2. Shown here one in and one out of their recharging case, Eargo hearing aids are designed to fit invisibly in the ear canal. Available for purchase on the Internet for around 2950 USD per pair, they feature rechargeable batteries and mesh with a cell phone, allowing users to adjust sound levels through an app. Credit: Eargo (public domain).

Some experts worry, however, that the new regulations put too much of a burden on consumers. The rules limit OTC sales to people with mild to moderate hearing loss, but consumers may not know if they fall into that category. A related concern is that people whose hearing loss results from medical conditions may go undiagnosed. Although Naples said he supports the coming changes, he is unsure ‘‘if patients have the intuition to say, ‘My hearing loss is more severe, and I need further investigation.’” And consumers will essentially have to become their own audiologist, choosing the right hearing aid and setting it up properly—a task many audi-ologists doubt they can accomplish. The process may be particularly challenging for elderly people who have difficulty using computers, let alone small, sophisticated devices that must be linked to smartphones. But Brian Earl, trained as an audiologist and now associate professor of communication sciences and disorders at the University of Cincinnati, OH, USA, said he is ‘‘tentatively in favor” of the changes if the FDA’s final rules accommodate audiologists concerns related to patient safety. ‘‘They are going in the right direction,” he said.

No country has attempted exactly what the United States is doing. A key indicator of how well the new FDA regulations are working, said Mormer, may be the number of customers returning purchased hearing aids to retailers. If consumers are satisfied with their first purchase, that will indicate that they are able to make appropriate choices. But if customers are returning the devices over and over, the regulations may need additional changes.

The procedures for obtaining hearing aids and the share of the cost covered by insurance vary from country to country [24]. However, Reed noted, even in the countries with the most generous coverage through national health insurance programs, less than 50% of the people who need hearing aids use them. Making hearing aids available OTC could improve that percentage even in these countries. The rest of the world, he said, will be watching what happens in the United States.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号