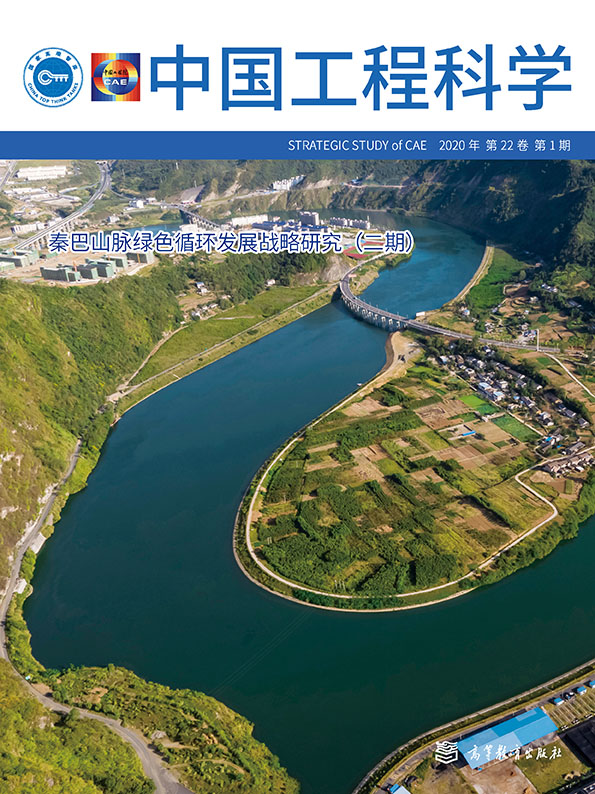

《1 Introduction》

1 Introduction

The Qinba Mountain Area includes both Qinling and Bashan mountain ranges, which cover five provinces of Shaanxi, Hubei, Sichuan, Henan, and Gansu, as well as the city of Chongqing, with an area of 308 600 square kilometers and 61.64 million population. Despite its unique ecological value as China’s central reservoir, ecological green lung, and biological gene pool, the region is also known for its abject poverty with the largest area and population among the 11 concentrated and extensive poverty-stricken areas in China [1]. The protected areas in Qinba Mountain Area have the highest ecological value but heavily affected by poor transportation, facilities, and economic conditions. Precisely, conservation policies here can deter local income earning. For instance, 40% of rural households living around protected areas in the Qinling mountain range claimed that environmental regulations have led to wildlife–human conflicts, which put constraints to timber and herb harvest and house construction [2]. Conversely, biodiversity suffers from human activities as well, such as grazing, illegal hunting and logging, and harvesting forest by-products, which cause habitat fragmentation of giant panda. Therefore, it is crucial to reduce the conflicts between conservation and development in Qinba Mountain Area for better environmental purposes and human settlement [3].

Community-based co-management (CBCM) is regarded as a process for communities to get involved in the decision-making, implementation, and assessment of protected areas to achieve the dual aims of conservation and sustainable development [4]. Since protected areas were initially established in China in the 1950s, many protected area authorities started to cooperate with communities for their initiative. For instance, Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve Authority (NNRA) embarked on joint forest management with residents in the 1770s. And later in the 1990s, the concept of the CBCM was initially introduced by non-governmental organizations. The International Crane Foundation introduced the idea of participatory management to Caohai National Nature Reserve (NNR) in Guizhou province. The Global Environment Facility initiated co-management pilots in Taibaishan, Foping, Zhouzhi, and other NNRs in Shaanxi province since 1995 [5], followed by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) that implemented Qinling project in 2002 to promote community conservation and local livelihood [6]. After that Conservation International (CI) embarked on Conservation Steward Program in Qinghai and Sichuan provinces [7], focusing on building agreements with communities to encourage conservation activities. According to relevant research in 2009, 87.0% of NNRAs in China tried to partner with communities [8], most of which failed due to various challenges. Then, the recommendation to build the CBCM mechanisms was officially stated in a policy guideline called Overall Plan for Establishing National Park System enacted jointly by the General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and General Office of the State Council in 2018.

The challenges between conservation and development caused protected area authorities to initiate the CBCM systems much earlier and in more diverse ways in Qinba Mountain Area than other places. Thus, some parts of those areas have achieved many positive outcomes. However, previous research papers are inadequate in terms of systematic analysis and comparative studies from a regional perspective, as most research mostly focused on single-case studies, e.g., Jiuzhaigou [9], Baishuijiang [10], and Foping [11] NNRs. Consequently, the experience sharing of successful cases refrains in this region, which limits learning opportunities for other protected areas.

In this article, we aim to compare among multiple typical cases of the CBCM in Qinba Mountain Area to analyze how the CBCM assists in coordinating between conservation and development and experiences learned. Also, we propose to improve the current arrangements.

《2 Research methods and case studies》

2 Research methods and case studies

《2.1 Research methods》

2.1 Research methods

Literature review, fieldwork, expert interviews, and comparative analysis are undertaken in this article. First, data of all the single-case studies of the CBCM in Qinba Mountain Area were collected. From the preliminary investigation, five typical cases were selected for more detailed reviews, including Jiuzhaigou NNR and Tangjiahe NNR in Sichuan province, Zhuhuan and Taibaishan NNR in Shaanxi province, and Baishuijiang NNR in Gansu province. Apart from that, we traveled to Shaanxi province in August 2017 and Sichuan and Gansu provinces in October 2018 to visit those CBCM cases. During that period, three panel discussions with protected area authorities, 12 interviews with protected area staff, and 31 interviews with community leaders and villagers held for more information and better understanding. They are all semi-structural interviews, focusing on its development process, co-management forms, and advantages and disadvantages combined with open-ended questions based on answers of interviewees and lasting from 60 to 90 minutes. The experts in community planning and co-management in both theoretical and practical fields were also interviewed, and each interview lasted 30 to 90 minutes. Then, after collecting the aggregate data from the literature review, fieldwork, and expert interviews, five selected cases were thoroughly analyzed and compared.

《2.2 Case studies》

2.2 Case studies

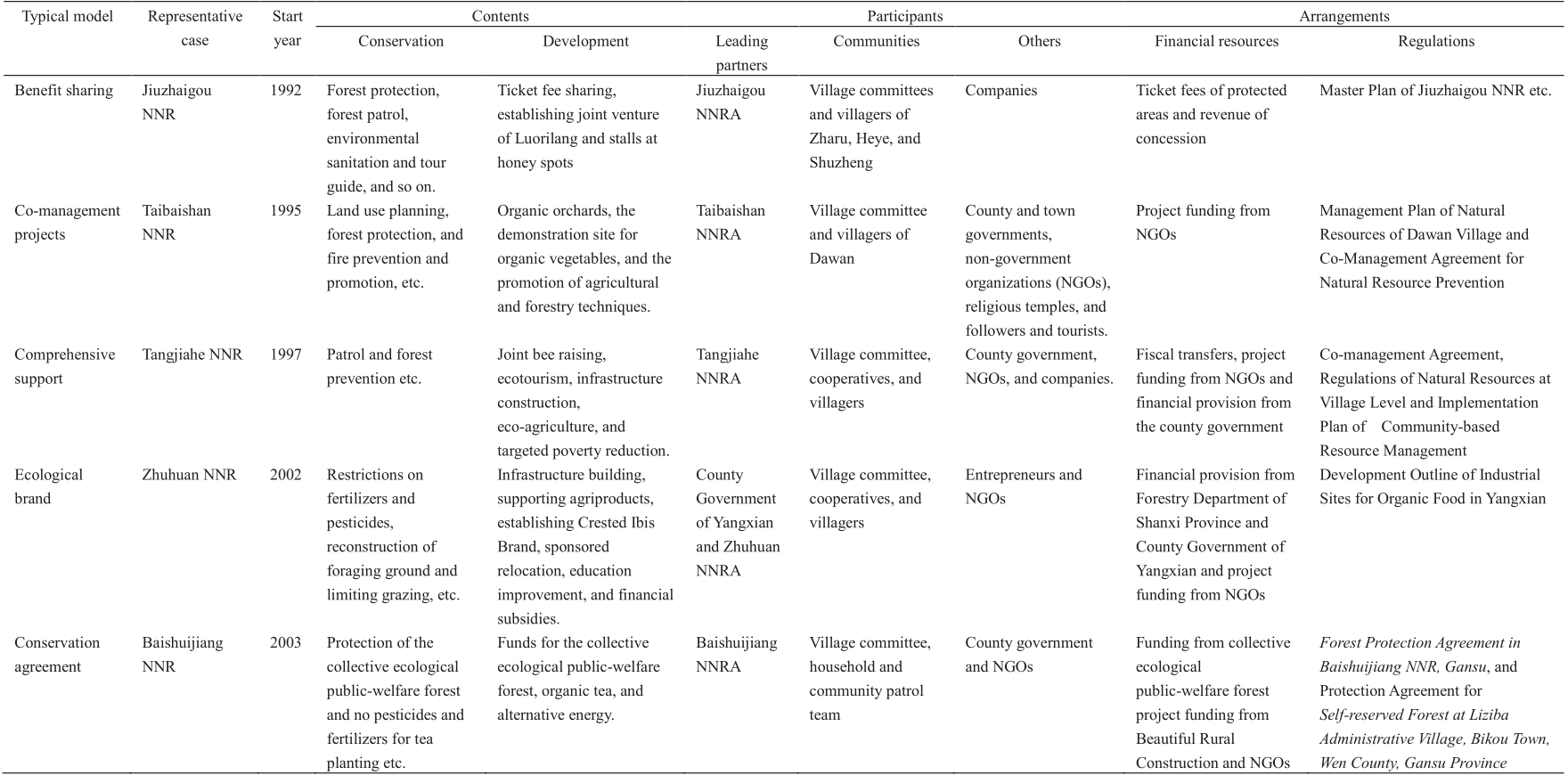

There are multiple factors to be considered when selecting the five cases, including information access, representativeness of cases, geological distribution, and so on. Large documents can be found about those cases, representing five different models of the CBCM, which are Benefit Sharing, Co-management Projects, Comprehensive Support, Conservation Agreement, and Ecological Brand. All these CBCM practices were initiated before 2003 and have been undertaken for more than 15 years. Therefore, relatively stable mechanisms and positive effects can be observed in both conservation and sustainable development aspects. Within the boundary of the study region, no literature of the CBCM is found in Hubei, Chongqing, and Henan provinces, so selected study cases are located in Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Gansu provinces.

Jiuzhaigou NNR stands for the Benefit Sharing model of the CBCM, as the authority brought benefits to communities by ticket fee sharing and mutual concession to ask for cooperation on natural resources protection [9]. The Taibaishan NNR represents the Co-management Project model of the CBCM for its co-management committee started from and implemented by projects sponsored by international organizations [12]. The authority of Tangjiahe NNR helped with communities to develop alternative livelihoods for conservation purposes using multiple methods, which we regard as a Comprehensive Support model [13]. The feature of the Conservation Agreement model is distinctive in Baishuijiang NNR, as Liziba village formed a four-level agreement among Baishuijiang NNRA, conservation station, administrative village, and petrol group/villagers [14]. The Zhuhuan NNRA established a commercial brand in the name of the Crested Ibis to promote the production, processing, quality assessment, and marketing of organic rice to make up for communities’ loss caused by the restriction of fertilizers and pesticides [15] (Table 1).

《Table 1》

Table 1. Typical cases of CBCM in protected areas in the Qinba Mountain Area.

《3 Coordination approaches of the CBCM》

3 Coordination approaches of the CBCM

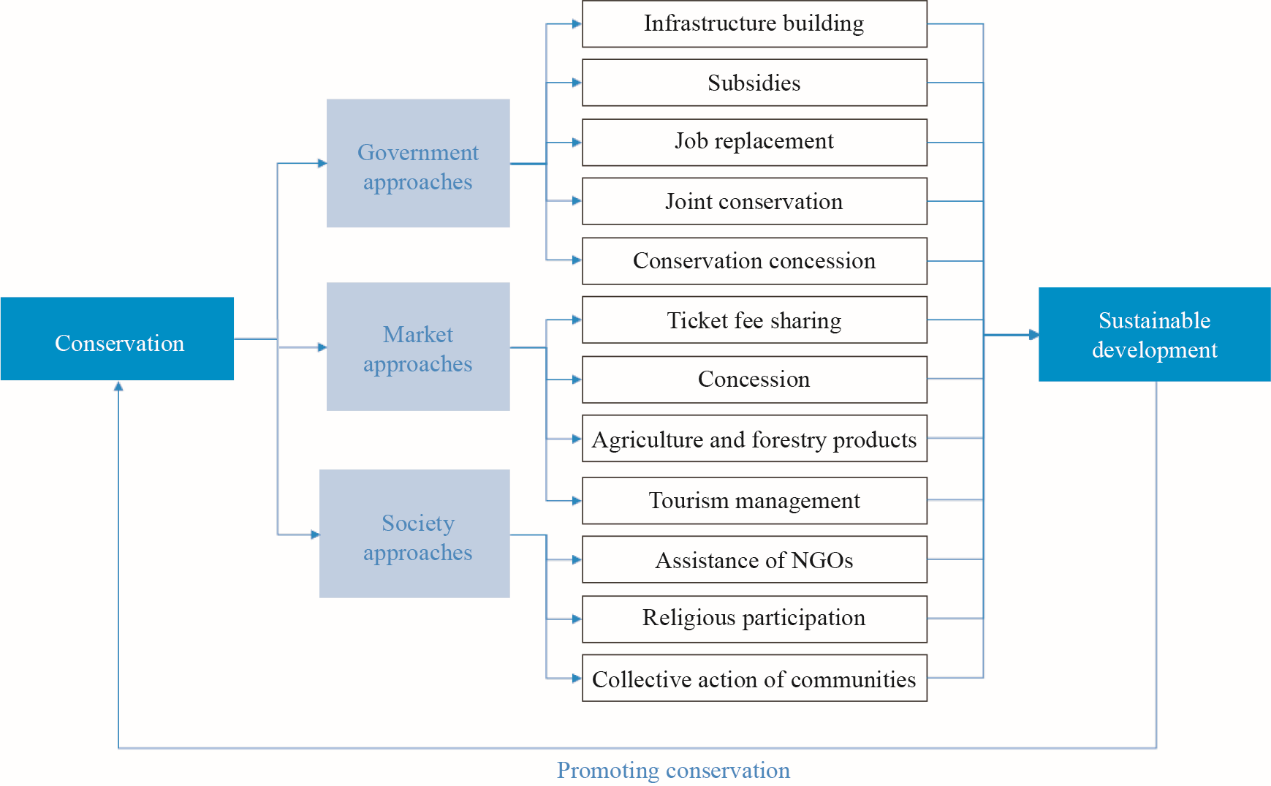

The traditional countermeasures to regulate communities in protected areas usually put conservation and development in opposite stands, thereby raising various conflicts among locals. However, with the novel idea of the CBCM, protected area agencies can seek support from the communities and allow resource utilization to a certain degree, thus reducing potential disagreements. By looking at five selected cases, three principal approaches of CBCM to coordinate between conservation and development are summarized in this study, namely from perspectives of the government, market, and society (Fig.1).

《Fig. 1》

Fig. 1. Coordinated approaches to conservation and development in case studies.

《3.1 Government approaches》

3.1 Government approaches

The government serves as a significant player in promoting the CBCM. For example, local governments and protected area authorities usually coordinate conservation and development using various measures, including facility construction, financial compensation, job placement, joint conservation, and conservation concession.

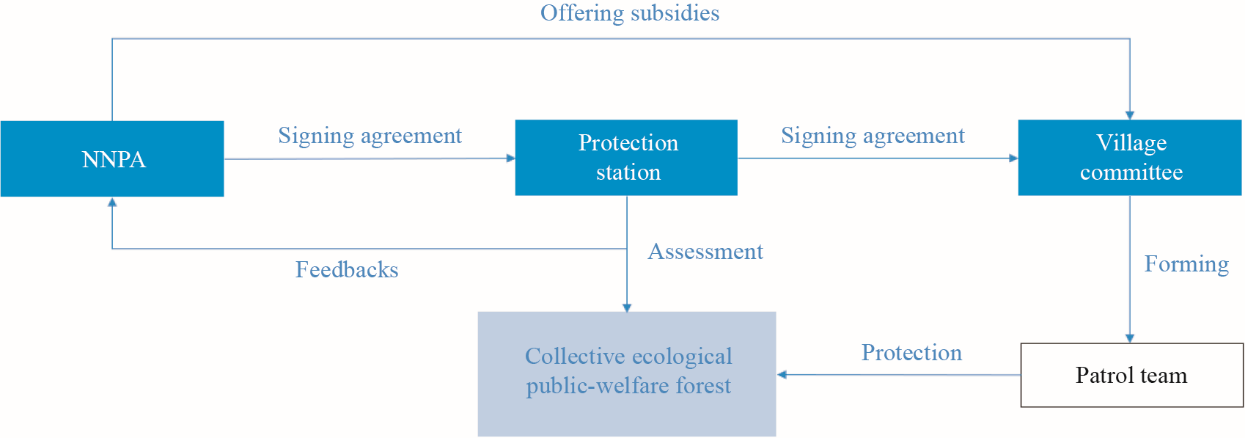

Government organizations improve the infrastructure to enhance local livelihood and reduce carbon emission, such as the medical station and reservoir building in Dawan Village in Taibaishan NNR [12]. Similarly, compensation can be offered by authorities to supplement households’ losses. For instance, Zhuhuan NNRA encouraged villagers to keep the paddy field in winter after harvest to provide feeding sites for Crested Ibis by offering compensation fees [15]. Besides, some protected area agencies provide jobs to communities to boost alternative livelihoods. In Jiuzhaigou NNRA, community members accounted for 41.35% of the workforce, participating in forest petrol, fire prevention, road maintenance, environmental health, and other fields [9]. Building cooperative conservation organizations involving protected area authorities, town governments, village committees, and other partners are recognized as another significant government approach [12]. For example, Taibaishan NNRA signed a joint fire prevention agreement with the local village committees. Moreover, it is helpful when government organizations delegate their authorities to village committees to empower the communities with conservation concessions. As demonstrated in the Liziba village of Baishuijiang NNR, where rights to protect collective ecological public-welfare forests are transferred to the village committee (Fig. 2) [19].

《Fig. 2》

Fig. 2. Conservation agreement system in Liziba Village of Baishuijiang NNR.

《3.2 Market approaches》

3.2 Market approaches

Various market approaches are also identified in this article in building community-based partnerships, such as ticket fee sharing, concession, organic products, and ecological tourism. They help to develop alternative livelihoods to reduce local dependence on natural resources.

First, ticket fee-sharing provides tourism-based profits for local communities. In Jiuzhaigou NNR, 7 yuan has been deducted from each ticket fee to encourage local income since July 2001, which brought almost 20 000 yuan annually per person [9]. Next, concession boosts local income, and the strategy is implemented in Jiuzhaigou, where NNPA established a joint venture company with communities and run a tourist service center called Nuorilang [9]. Also, it is helpful to transfer ecological restrictions into industrial growth point to support villagers to produce and sell organic agriculture and forest products, as in the brand “Crested Ibis” selling organic rice in Yang County [18]. The protected area authorities chose to develop community-based tourism and support residents in agritainment and homestays to achieve industrial transformation. For example, the Yinping village has provided 3000 jobs for residents by developing agritainment with assistance of Tangjiahe NNRA.

《3.3 Society approaches》

3.3 Society approaches

Social partners like NGOs, religious groups, and community organizations have contributed significantly to achieve both conservation and development initiatives.

The NGOs play various functions in the CBCM arrangements, including financial support, technical training, platform building, and communication. In Baishuijiang, Tangjiahe, Taibaishan, and Zhuhuan NNRs, it is clear that the WWF, GEI, and Shanshui Conservation Center have a significant impact on the coordination [6]. Moreover, some religions in China, such as Buddhism and Taoism, embrace the ideology of co-existence between human beings and nature, which support conservation. For example, the Taibaishan NNR with 26 relics of religious temples, where local believers joined in planting trees and grass, promoting environmental-friendly awareness, and monitoring natural resources [12]. This type of CBCM approach is largely context-relevant. Moreover, the collective action of communities can unleash bottom-up power to mobilize communities to take the initiative in conservation. In 2003, faced with illegal hunting and felling from intruders, the village head Ma Xiaolun applied to the government for authorization and funding to organize a 20-personal forest patrol group, serving as the foundation of the later formed mechanism of conservation agreement [19].

《4 Experiences and issues of CBCM》

4 Experiences and issues of CBCM

《4.1 Experiences》

4.1 Experiences

From the previous comparative analysis of the CBCM, four lessons are thereby identified, that include government dominance, multiple approaches, regional features, and system innovation.

4.1.1 Leading by governments

Governments take dominance in five selected cases, whereas market-based countermeasures and social suppliers serve as supplementary. The close cooperation between the protected area agencies and the local government suggests a secure integration of top-down power. It is demonstrated in the Jiuzhaigou case study where protected area authority replaced part of a function that initially belong to the county government [20]. In the Zhuhuan case study, Yangxian County Government puts great efforts in Crested Ibis protection in terms of political, financial, and labor ways. Besides, governments also contribute to the majority of market-based approaches, such as ticket fee sharing and concession in Jiuzhaigou, ecological brand building in Jiuzhaigou, and ecotourism development in Tangjiahe. Even in the conservation agreement mechanism initiated by communities in Liziba village, the empowerment of county government and monitoring of protected area agencies have imposed momentous impact.

4.1.2 Adopting multiple approaches

The success of the CBCM is primarily based on multiple approaches, which are adaptable to local contexts. As contexts can vary with various features of communities and changeable conditions of the environment, the plurality here can enhance its systematic adaptivity. All case studies are undertaken by concerted efforts from the government, market, and society altogether, while more than five methods of coordination are adopted in each case (Table 2). Taking Tangjiahe NNR as an example, the authority implemented infrastructure building, financial compensation, job placement, and joint conservation as government approaches; developed agricultural and forestry products and ecotourism as market-based approaches, and socially built close cooperation with NGOs.

《Table 2》

Table 2. CBCM approaches to coordinate between conservation and development.

4.1.3 Reflecting regional features

In terms of the coordination approaches of conservation and development, all the five cases display its regional features to some degree, which can be reflected in four aspects: ecotourism, organic products, ecological culture, and environmental policy. Ecotourism in this area is well developed on the basis of natural sceneries, as shown in the Jiuzhaigou case study, where ticket fee sharing and concession mechanism are performed based on its tremendous attraction to tourists. Moreover, the forcefully imposed restrictions on resource extraction can ensure a better quality of organic agricultural and forestry products, without pesticides, fertilizers, and additives which might be harmful to consumers’ health for long-term use, therefore increasing added value and price of these products. The abundant culture in Qinba Mountain Area, part of which respects the environmental-friendly perception and mobilized its believers in conservation, is another regional feature acting effectively in the CBCM mechanism building, demonstrated in the Taibaishan case study. Finally, the restricted and prohibited development zones account for approximately 2/3 of the Qinba Mountain Area, which means that practitioners of the CBCM need to comply with or make full use of local ecological policies. Liziba village obtains the CBCM funding from collective ecological public-welfare forest subsidies in the Qinba Mountain Area, which suggests its highly circumstantial adaption to local environmental policies.

4.1.4 Making system innovation

Every CBCM arrangement can make its breakthrough innovatively. In each case study, innovation points are detected evidently. The Zhuhuan NNRA finds its distinctive way in the establishment of “Crested Ibis Brand” to produce organic rice, considering the particular requirements of Crested Ibis conservation. In the Baishuijiang case study, the NNRA was inspired by Conservation Steward Program and then adapted to its local contexts by forming a four-level agreement. The previous policy of “traveling inside the valley, staying outside valley” in Jiuzhaigou was replaced by its newly formed ticket fee sharing arrangement for its failure to control tourists’ behaviors. The Tangjiahe NNRA added a religious sentiment to the CBCM for the first time while Tangjiahe NNRA advocated raising bees jointly with communities without precedent, as one of its comprehensive supportive methods.

《4.2 Problems》

4.2 Problems

The CBCM arrangements in the Qinba Mountain Area faced various challenges, including incomplete eco-industry, low community empowerment, unrecognized eco-cultures, and insufficient state support.

4.2.1 Incomplete eco-industry

The environmental industries in the Qinba Mountain Area are not fully developed currently, limiting livelihood options from communities and consequently hindering the sustainable development process. It demonstrated by insufficient standards of eco-products and inadequate regulation of ecotourism. For instance, in the promotion of “Crested Ibis Brand,” authorities have confronted many challenges to applying for the organic certificate of products, which can reveal loopholes of standard authentication at regional and national levels. In the Jiuzhaigou case study, packed tourists consume a large quantity of food and dispose of a significant amount of waste, thereby putting a strain on conservation in its peak season [21]. The traditional perception of communities shifted from a more eco-conscious to a more profit-oriented way, impacted by the mass tourism that failed to prioritize ecological concerns [22].

4.2.2 Low community empowerment

Certain protected area authorities failed to ensure fundamental land rights of communities and their access to natural resources and also refused to empower them. Therefore communities seldom get motivation indeed and to be fully involved. Bottom-up initiatives are rare to be identified, merely appeared in Baishuijiang case study when faced with an exterior threat from intruders. Also, communities are often equipped with relatively low environmental awareness and conservation-relevant capabilities depicted in all cases, which makes them less likely to be empowered in conservation and unlikely to make a living in ecological industries. In this way, low community empowerment and capability has hindered both the conservation and sustainable development in the CBCM arrangements.

4.2.3 Unrecognized eco-cultures

With a long history and great cultural diversities, the Qinba Mountain Area is home to many of the traditional cultures that highly admire nature, including religious culture, reclusive culture, ethnic minority culture, and mountain aesthetic culture [23]. Historical resorts for reclusive groups to practice Buddhism and Taoism or collect herbs in pursuit of longevity are detected in Zhongnan, Wudang, Qingcheng, Emei, and Daba Mountains in Qinlin and Bashan mountain ranges. However, those ecologically-minded cultures are not entirely recognized and practiced in modern times. They have not been integrated into the contemporary eco-industry chain to produce economic value and can often face challenges in expanding its influence on followers. The Taibaishan NNR can be seen as a model in leading communities to conservation by exerting religious influence, which is worthwhile to be referred to by other protected areas similar cultures.

4.2.4 Insufficient state support

CBCM mechanisms can face several obstacles without sufficient legislative, political, and financial support from central governments. In our interviews, staff working in five NNRAs all think there is a lack of legislation in the CBCM arrangements, which can make these mechanisms less convincing for communities to participate. Apart from the Jiuzhaigou case, four other NNRs suffered from a financial shortage in promoting the CBCM. Consequently, Baishuijiang NNRA sponsored its conservation agreement with collective ecological public-welfare forest subsidies, which is referential for other protected areas to seeking financial support.

《5 Theoretical reflection and policy recommendation of the CBCM》

5 Theoretical reflection and policy recommendation of the CBCM

《5.1 Theoretical reflection》

5.1 Theoretical reflection

Case studies specify how the CBCM arrangements in protected areas are coordinated between conservation and sustainable development. Also, the studies reveal that three pairs of relationships, which include equity vs. efficiency, centralization vs. decentralization, and public welfare vs. individual benefits, should be handled appropriately in the process.

5.1.1 Equity vs. efficiency

Unlike equity, efficiency has been easily achieved in promoting sustainable development in the CBCM. The reason is due to the limited selection of demonstration sites, which frequently provides more opportunities and resources to selected ones than non-selected. Whereas Baishuijiang NNRA appointed Liziba village as the pilot zone of co-management, Taibaishan NNPA chosen Dawan village as well, consequently widening the resource allocation gap between the demonstration and non-demonstration sites. Moreover, benefit distribution can also add to the inequity in co-management cases. Most cooperatives producing agriproducts and developing ecotourism can only benefit a specific group of residents; thus far might have to ignore others. Even the shareholding cooperative system in the Jiuzhaigou case cannot promise complete fairness due to a frequent population change despite of its principle of equity.

5.1.2 Centralization vs. decentralization

Decentralization is the key to pursue the CBCM, and it demands to gain more authorities, responsibilities, and benefits to communities. However, it is only demonstrated in the Baishuijiang case that the village committee of Liziba was empowered by the county government with conservation concession to ensure accountabilities. In the other four cases, the authority and responsibility of conservation are tightly held by NNRAs, yet rewards are mostly distributed to communities through financial means. The results in communities significantly ignore conservation purposes and usually focus simply on monetary feedbacks. Thus, without community empowerment, the term CBCM has three implications, communities being managed, forced to manage, or superficially managing.

5.1.3 Public welfare vs. individual benefits

As a link connecting the public welfare of conservation and individual benefits of sustainable development, the CBCM is often operated as public, yet for individual interest purposes. From the case studies, loads of local governments implement the CBCM solely for local livelihood. A majority of residents regard the CBCM as a money-making tool, thus measure their input based on monetary rewards. As stated in Jiuzhaigou NNR, the overfocussing on tourism development and economic benefits has threatened the local environment and jeopardized cultural diversity.

《5.2 Policy recommendation》

5.2 Policy recommendation

To coordinate between conservation and sustainable development in the Qinba Mountain Area, it is crucial to strengthen the CBCM arrangements at national, regional, and protected area unit levels.

5.2.1 At the national level

The central government remains a strong player in building the CBCM mechanisms in Qinba Mountain Area, both legally, politically, and financially. It is recommended to enact Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Community Rights in Protected Areas for National People’s Congress to ensure the necessary land, economic, and political rights of residents. The item of building the CBCM arrangements should be included in this act. Also, the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, and Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs should collaborate to set policy pilots of the CBCM in Qinba Mountain Area and encourage innovative mechanisms. A special fund for building the CBCM mechanisms is proposed to be applied to protected area authorities in nature reserves, scenic spots, forest parks, and other conservation spaces.

5.2.2 At the regional level

Here, it is advisable to explore adaptable approaches with distinctive regional features in four aspects: community-based ecotourism, eco-agriproducts, eco-culture, as well as eco-policies. First, community-based ecotourism can be a prospective option to develop local livelihoods in the Qinba Mountain Area with plentiful pleasant sceneries. Second, developing diverse community-based eco-agriproducts is also a promising direction, as communities in this region highly depend on agriproducts and locals. Thus, building a regional brand in Qinba Mountain Area is essential for conducting an environmental assessment, enacting quality standards, and promoting eco-products. Next, community-based eco-culture emerged in this area can be developed and promoted to motivate communities in conservation and to add an addition to eco-industries in various fields, such as health, research, and environmental interpretation. Finally, eco-policies in this region are considered to sponsor, motivate, and monitor communities in coordination between conservation and sustainable development.

5.2.3 At the protected area level

For the protected area authorities in the Qinba Mountain Area, the following four fundamental principles are proposed here to strengthen the CBCM arrangements: community empowerment, adaptivity, multi-participation, and equity. Thus, community empowerment is vital in this collaboration. When protected area agencies delegate power and offer ability training to lower levels, communities are regarded as equal partners rather than merely subordinates, and then would be better mobilized in terms of engagement. Moreover, adaptivity is also a key as the CBCM mechanisms should be adjusted according to time, location, and specific groups and adaptable to local contexts. A strong partnership with multiple players, including local governments, NGOs, entrepreneurs, communities, tourists, and the public, should not be neglected to build to integrate resources and reach consensus. Last, equity is another ground rule, which is essential to avoid conflicts among various groups. It is advisable to remain fair and unbiased among different communities or groups, especially on occasions with profits distribution.

《Acknowledgment》

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Liao Lingyun, Zhang Aiping, Peng Kui, Li Shenzhi, Xie Yan, Tian Feng, Feng Jie, Zhang Yingyi, and He Liwen for their interviews or other support rendered for this article.

京公网安备 11010502051620号

京公网安备 11010502051620号